To say that Hungary is no longer a democracy is a stark claim and I have thought, read and looked hard before making it, notes Oxford University’s Timothy Garton Ash.

To say that Hungary is no longer a democracy is a stark claim and I have thought, read and looked hard before making it, notes Oxford University’s Timothy Garton Ash.

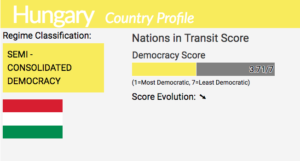

Often people apply the term that Viktor Orbán has himself used approvingly: “illiberal democracy”. But illiberal democracy is a contradiction in terms. That label may usefully describe a transitional phase in the erosion of a liberal democracy, such as we see in Poland, but Hungary is way beyond that. This year the human rights organisation downgraded it to the status of “partly free” country, the only EU member state to earn that dishonour, he writes for The Guardian:

The EU must stop this tragic farce of its own funds being used to undermine European values. It should appoint as European public prosecutor the Romanian Laura Codruţa Kövesi, who knows exactly what post-communist, east European corruption looks like, and make signing up to scrutiny by that European public prosecutor a condition for receipt of those funds. It should also move to distribute more EU funding directly to local government and civil society, rather than letting it be used as a huge, centralised slush fund by a corrupt party-state.

The EU must stop this tragic farce of its own funds being used to undermine European values. It should appoint as European public prosecutor the Romanian Laura Codruţa Kövesi, who knows exactly what post-communist, east European corruption looks like, and make signing up to scrutiny by that European public prosecutor a condition for receipt of those funds. It should also move to distribute more EU funding directly to local government and civil society, rather than letting it be used as a huge, centralised slush fund by a corrupt party-state.

How did the Orbán of the early ’90s, with his long hair and academic aspirations, become the architect of illiberalism? Franklin Foer writes in a must-read analysis for The Atlantic Monthly:

One theory suggests that political expediency pulled him to the right. But the liberals had also wishfully imposed their hopes on Orbán, never looking carefully enough at him to notice that he deeply resented them. “The dorm kids always wanted to show the urban intellectuals that they had always been the smarter, better leaders,” Scheppele told me……

People often ask me why Hungarians do not revolt against such rampant patronage politics and concentration of power, former lawmaker Zsuzsanna Szelenyi writes for the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy:

People often ask me why Hungarians do not revolt against such rampant patronage politics and concentration of power, former lawmaker Zsuzsanna Szelenyi writes for the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy:- First there is the sheer scale of the distortion to Hungary’s constitutional and electoral systems, which explains why the party could win a supermajority with only 44 per cent of the vote.

- Then there is the distracted and fragmented opposition, composed of half a dozen parties that have shown little ability to cooperate. But other factors run deeper.

- Orban’s nationalism resonates with Hungarians who are still mindful of the national tragedy of the Treaty of Trianon, which stripped Hungary of 67 per cent of its territory and 58 per cent of its population at the end of World War I. Trianon not only smashed the physical entity of Hungary but wounded the identity and dignity of Hungarians.

So when Orban says he is reclaiming Hungary’s sovereignty today, he is playing on Hungarians’ historic grievances, Szelenyi contends. RTWT

Balkan Investigative Reporting Network