Extreme intolerance has replaced the liberal notion of negotiated compromise that is the sine qua non of democracy, argues Andrew A. Michta, dean of the College of International and Security Studies at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies.

The American nation has its dark sides, with slavery remaining a deep scar on its history. Nonetheless, the power of the American ideal offered millions something that no other culture could, namely the chance to reinvent and renew one’s life, advance one’s position, and create a better future for one’s children, he writes for The Wall Street Journal:

The passionate nationalism of America has been rooted in the belief in exceptionalism as a people ordained for greatness, and that equality of opportunity under the law could constrain the base impulses of man. It is a tragedy that the young seem to have jettisoned this foundational American ideal, or more likely were never exposed to it in the first place. The traditional view that political victory and loss are both part of the democratic process and the gist of a self-constituting polity has been replaced with a Leninist drive to nullify one’s opponent.

If the institutions of American democracy are separated from their national foundations, “the U.S. will over time lose its republican culture and morph into a state in which the new aristocracy wields power over a disenfranchised and impoverished populace,” Michta cautions.

A decline in courage may be the most striking feature which an outside observer notices in the West, said Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (above) in A World Split Apart, his 1978 Harvard commencement address.

“The Western world has lost its civil courage, both as a whole and separately, in each country, each government, each political party, and, of course, in the United Nations,” he stated. “Such a decline in courage is particularly noticeable among the ruling groups and the intellectual elite, causing an impression of loss of courage by the entire society. Should one point out that from ancient times declining courage has been considered the beginning of the end?”

Extreme intolerance has now replaced the liberal notion of negotiated compromise that is the sine qua non of democracy, argues @andrewmichta https://t.co/FFNyIWMRyj via @WSJ

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 26, 2020

In his address, Solzhenitsyn says that Western societies place a strong emphasis on freedom and rights. At the same time, he observes, there has been a notable decline in individual obligations, or personal responsibility, notes Sergiu Klainerman, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Mathematics at Princeton. This imbalance between rights and responsibilities is not only restricted to individuals, it is also affecting our governmental, societal, and cultural institutions, he writes for Quillette:

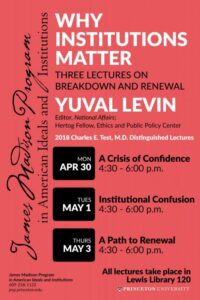

In a series of lectures at Princeton University two years ago, Yuval Levin decried how these institutions are neglecting their formative responsibilities in favor of performative actions. He provides a thorough analysis of how congressmen, journalists, judges, and university professors prefer to behave, often to the detriment of the institutions they represent, as independent actors on the larger stage provided by the irrepressible, omnipresent, and vastly irresponsible media. The result is an accelerating lack of trust in the institutions they represent and a decline of social capital, which is essential to the health of the republic.

Different visions of civil society express a view of American social life that consists, in essence, of individuals and a national state, notes Levin, editor of National Affairs, and the author, most recently, of The Fractured Republic: Renewing America’s Social Contract in the Age of Individualism.

Different visions of civil society express a view of American social life that consists, in essence, of individuals and a national state, notes Levin, editor of National Affairs, and the author, most recently, of The Fractured Republic: Renewing America’s Social Contract in the Age of Individualism.

“The dispute between left and right in this regard is about whether individuals need to be liberated from the grasp of the national state or need be liberated by that state from would-be oppressors among their fellow citizens,” he adds. “Civil society is seen as a tool for doing one or the other. Such visions, in other words, tend to ignore the vast social space between the individual and the national state—which is after all the space in which civil society actually exists.”

The imbalance between rights and obligations in Western societies is constantly growing as the common understanding of rights is expanding, thus strongly undermining any remaining notions of individual obligations, Klainerman adds. RTWT

Growing polarization is feeding distrust in democratic institutions, The Washington Post reports.

“The two sides have come to view each other not as opponents, but as deeply evil,” said Peter Stearns, a historian of emotions at George Mason University. “And that’s happening when trust in institutions has collapsed and each group is choosing not to live near each other. It seems there’s no middle ground.”

“The two sides have come to view each other not as opponents, but as deeply evil,” said Peter Stearns, a historian of emotions at George Mason University. “And that’s happening when trust in institutions has collapsed and each group is choosing not to live near each other. It seems there’s no middle ground.”

“I didn’t take it seriously for a long time, but in the last six weeks, it’s become very concerning,” said Michael Barkun, a political scientist at Syracuse University who studies political extremism. “This idea that the other side winning the election will produce a precipitous decline and the disintegration of institutions is completely at variance with American history.”

Reflections on Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard Address – Quillette https://t.co/7nT0qsziOb via @Quillette

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 26, 2020

Rebuilding civic architecture, renovating democratic institutions and renewing the legitimacy of democracy will foster the resilience of societies and help preserve liberal-democratic values, according to Renewing Democracy in the Digital Age, a report from the Berggruen Institute Future of Democracy program.