Russian President Vladimir Putin named a new prime minister, who was confirmed (Reuters) one day after his predecessor resigned along with Russia’s entire cabinet. Putin also proposed changes (FT) in responsibilities allocated between top political posts, a move seen as a gambit to let him remain in power after his presidency, the Council on Foreign Relations reports.

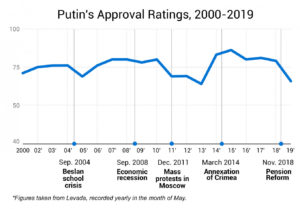

One reason for [Putin’s] removal of Dmitri Medvedev may have been fears that the prime minister’s unpopularity would drag Putin’s approval ratings down from their current position in the high 60s, The Washington Post reports. An October opinion poll by the Levada Center found that 72 percent of Russians believed the government’s interests were not aligned with those of the population, and 53 percent thought the government lived off the people and did not care how they survived.”

Levada

Indeed, over the last year, Russia has seen its most vigorous street protests since the anti-Putin rallies of 2011 and 2012. Polls show that Russians increasingly distrust pro-Kremlin TV channels and are getting their news on the internet, which remains largely uncensored, The New York Times reports:

And the Kremlin’s appeal to patriotism — so effective after Mr. Putin’s annexation of the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea in 2014 — has lost its visceral power, overshadowed by Russia’s economic problems…. While Russians do increasingly blame Mr. Putin for their ills, many more blame the bureaucrats below him. Mr. Putin’s approval rating has fallen to 68 percent from 82 percent in April 2018, an independent pollster, Levada, says.

Crimea Doesn’t Pay

Real wages have mostly stagnated or fallen since Mr. Putin returned to the Kremlin in 2012 after a four-year interlude as prime minister. He has attributed the poor economic record to the Western sanctions imposed over his annexation of Crimea in 2014, The Times adds.

Putin’s claim that the amendments are intended to “strengthen the role of civil society, political parties and regions in making key decisions about the development of our state” will be greeted with skepticism if not derision given the regime’s crackdown on dissent.

Putin’s claim that the amendments are intended to “strengthen the role of civil society, political parties and regions in making key decisions about the development of our state” will be greeted with skepticism if not derision given the regime’s crackdown on dissent.

The European Parliament recently called on Russian authorities to repeal a controversial law on “foreign agents” – which has targeted the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and other democracy assistance NGOs – and to “stop deliberately creating an atmosphere that is hostile to civil society.”

For several years now, Russia has been the scene of growing mobilization, whether through the action of NGOs or civil society. What are the arms of the Russian state against NGOs and civil society? How will the situation evolve? Ilya Nuzov, head of the International Federation for Human Rights Eastern Europe offers answers (above).

Kazakh model?

Levada

Medvedev’s move to Russia’s Security Council, which Putin chairs, has added to speculation that Putin may be looking to copy the path of a former Soviet republic, Kazakhstan, in retaining power past his presidency. Last March, Nursultan Nazarbayev, Kazakhstan’s long-serving president, stepped down but became chairman of the Security Council for life — making him the effective power broker, The Post adds.

“This is all about how to influence the prerogatives of the future president,” said Tatiana Stanovaya, the head of R.Politik, a think tank. “Putin would like to have some leverage, some mechanism to control and to get involved, in case his successor makes mistakes or has some disagreements with him.”

“He doesn’t want to get engaged in routine social and economic policy, like the budget — it’s boring for him,” Stanovaya said. “He wants to focus on foreign policy, and I think the State Council is much more convenient for him. But for that, he will need to make it a constitutional body and significantly enlarge its possibilities.”

In the end, Russia’s revamped political system may come to resemble a version of Iran’s Guardian Council, with a permanent, unelected Ayatollah at the top, argues former Penn Kemble fellow Maria Snegovaya. In this sense, Russia’s new institutional design may look even less democratic and less competitive than the Kazakh model, she writes for CEPA.

Putin is paying a backhanded tribute to democracy, argues Leon Aron, Director of Russian Studies at the American Enterprise Institute and the author of Roads to the Temple, Yeltsin, and several other books. For all the power that Putin wields in Russia, very few people can rule a country in the 21st century without at least a veneer of democratic procedure. Putin has always paid lip service to “democracy” and “freedom.” writes for The Atlantic:

Putin is paying a backhanded tribute to democracy, argues Leon Aron, Director of Russian Studies at the American Enterprise Institute and the author of Roads to the Temple, Yeltsin, and several other books. For all the power that Putin wields in Russia, very few people can rule a country in the 21st century without at least a veneer of democratic procedure. Putin has always paid lip service to “democracy” and “freedom.” writes for The Atlantic:

Well into his 20th year as Russia’s leader, Putin represents the global template for a new era of authoritarians, Susan B Glasser writes for Foreign Affairs.

Every move the Kremlin makes on the political field today shows that ‘the mechanisms of administration which have been in place for two decades have exhausted themselves and that the Kremlin has not been able to put in place a new model of rule,” analyst Liliya Shevtsova (left) recently observed.

Every move the Kremlin makes on the political field today shows that ‘the mechanisms of administration which have been in place for two decades have exhausted themselves and that the Kremlin has not been able to put in place a new model of rule,” analyst Liliya Shevtsova (left) recently observed.

Putin’s approval ratings remain high — about 68 percent, according to a December poll from the Levada Center — but they have been gradually declining because of unpopular moves in recent years to raise the retirement age and increase taxes on goods and services, The Washington Post adds.

Indeed, poverty among young Russians will cast a shadow long into the future, analysts suggest (HT: Paul Goble’s Window on Eurasia).

Simply put, Putin has informed the Russian people how he will wish to manage Russia and its so-called “managed democracy” to the betterment of his future, argues Heather Conley, Europe Program Director at the Center for Strategic & International Studies.

The Russian opposition, of course, has read the signals, too, Leonid Bershidsky writes for Bloombergg (HT:FDD):

“The main outcome of Putin’s address: How dumb and/or crooked are all those who said Putin would leave in 2024,” tweeted Alexey Navalny, Putin’s best-known political opponent. Indeed, whatever the formal shape of the political system Putin intends to create at the end of his presidency, Russia’s real constitution is in Putin’s head. That’s where the missing details will come from, too.

“The main outcome of Putin’s address: How dumb and/or crooked are all those who said Putin would leave in 2024,” tweeted Alexey Navalny, Putin’s best-known political opponent. Indeed, whatever the formal shape of the political system Putin intends to create at the end of his presidency, Russia’s real constitution is in Putin’s head. That’s where the missing details will come from, too.

Putin is in effect saying, “only I can fix it” and that he should therefore rule indefinitely, according to a former US Ambassador to Russia. Putin’s proposals to increase the authority of the parliament may be presented as moves to increase democratic accountability, but are more likely window dressing, says Alexander Vershbow, Distinguished Fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Transatlantic Security Initiative.

Is a ‘Soviet Revanche’ Possible?

Levada

Putin and his siloviki backers could still decide on a “red coup” if they see it as the only chance to avoid a bloody popular rebellion, analyst contends. Much will depend on whether the liberal opposition can win over the majority of dissatisfied Russians and thereby prevent the Kremlin from preempting further protests, she writes for Jamestown’s Eurasia Daily Monitor:

Polling data shows that the majority of Russians dissatisfied with their government’s policies do not hold liberal views but rather dream of reviving the “red project.” According to a survey released by the Levada Center in December of last year, the number of Russians nostalgic for the USSR is the highest it has been in the past ten years, reaching 66 percent. Moreover, the glorification of the Soviet Union is also growing among younger people (BBC News–Russian service, December 19, 2018). The year 2019 was also marked by the highest level of positive feelings for former Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin since Levada Center’s polling began. According to an April survey, Russians’ favorable or neutral views toward the Soviet leader stood at 77 percent (Levada.ru, April 16, 2019).

Clearly, many Russians embrace Putin’s model for ruling the country: respect for the right of the strongest, Daily Beast‘s Anna Nemtsova writes: “Nobody knows how to make an authoritarian country with a huge nuclear arsenal obey international law, except to recognize its power,” said analyst Alexander Golts. And nobody knows that better than Vladimir Putin.