Credit: Janjira Sombatpoonsiri/Carnegie

Political turmoil isn’t new in Thailand, which has been rocked by coups and periods of unrest for decades. But a new generation of Thais has taken to the streets in recent months against a system they see as dictatorial and out-of-place in the 21st century, with some questioning the very foundation of what it means to be Thai, The Wall Street Journal reports (HT: FDD).

The voices of Thailand’s children who are demanding democratic reform are increasingly reverberating around the world, says Sunai Phasuk, the senior Thailand researcher at Human Rights Watch. They have held their own rallies on school grounds and occasionally taken to the street, including at the largest democracy rally to date, on Aug. 16 at the Democracy Monument in central Bangkok, he writes for The Washington Post:

Credit: NDI

On that day, tens of thousands of peaceful protesters called for the dissolution of parliament, drafting of a new constitution, ensuring respect for freedom of expression and other human rights, and perhaps most controversial of all, for reform of the monarchy to curb King Vajiralongkorn’s broad powers…..Thai Lawyers for Human Rights, which provides legal assistance to the Bad Students, reported that police officers have gone into schools to intimidate students by taking photos and questioning children who participated in rallies or Bad Students campaigns. … One high school student in Ratchaburi province was even charged with illegal assembly, which carries a maximum two-year prison term. RTWT

Democracy activists and protesters have hit the streets as they have little hope for victory through the legislature, adds analyst Evan Shilling. Thailand’s most progressive political party to date was prevented from growing into a voice of change in the country’s notoriously rigid parliament, he writes for the Center for International Private Enterprise, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED):

The Future Forward Party was dissolved by the Thai Constitutional Court in February 2020, banning party leader Thanatorn Juangroongruangkit and party executives from politics for 10 years. The court found that funds donated by Juangroongruangkit to the FFP to exceed the allowable limit imposed by the Political Parties Act. The dissolution was conveniently timed to disrupt the opposition ahead of several censure debates.

![]() The Asia Democracy Network, a coalition of civil society groups, has called on the Thai authorities to respect the basic freedoms of expression and assembly.

The Asia Democracy Network, a coalition of civil society groups, has called on the Thai authorities to respect the basic freedoms of expression and assembly.

But the students do fear for their safety, the BBC adds. At least nine activists who fled overseas since the 2014 coup against the military-led government have disappeared after criticizing Thailand’s most revered institution. The bodies of two of them were later found on the banks of a river.

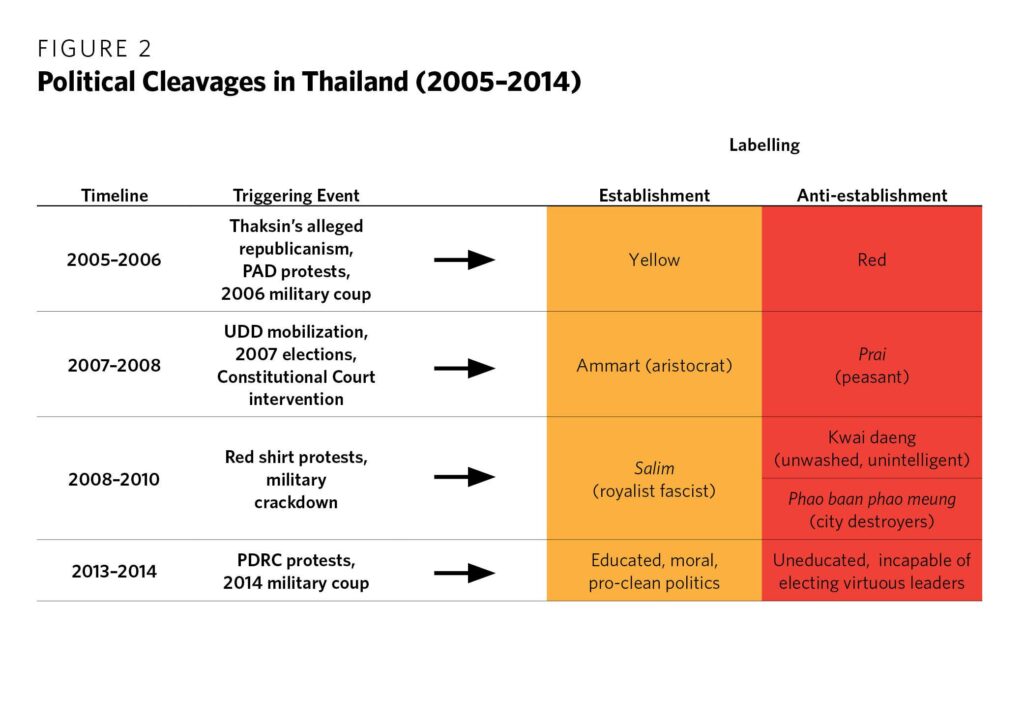

The crux of polarization in Thailand is a sharp division between two worldviews that seek incompatible political orders, notes Janjira Sombatpoonsiri, a researcher at the Institute of Asian Studies at Chulalongkorn University in Thailand. The royal nationalist worldview regards the Thai king as the country’s legitimate ruler; the competing democratic outlook contends that sovereignty resides with the Thai people, she wrote in a recent Carnegie report, Political Polarization in South and Southeast Asia: Old Divisions, New Dangers.

The crux of polarization in Thailand is a sharp division between two worldviews that seek incompatible political orders, notes Janjira Sombatpoonsiri, a researcher at the Institute of Asian Studies at Chulalongkorn University in Thailand. The royal nationalist worldview regards the Thai king as the country’s legitimate ruler; the competing democratic outlook contends that sovereignty resides with the Thai people, she wrote in a recent Carnegie report, Political Polarization in South and Southeast Asia: Old Divisions, New Dangers.

The country’s existing ideological divide has hindered meaningful cross-camp cooperation at both the elite and societal levels. Pro- and anti-establishment civil society groups have launched their own separate charitable programs and at times have even discredited the other side’s efforts. The pandemic has reignited debates over clashing notions of Thai identity as well, Sombatpoonsiri adds.

Potentially consequential events are ahead, Geopolitical Monitor’s Mark S. Cogan suggests.

Thai history over the past four decades has demonstrated that the past is prologue to future events. Student revolutions have been silenced by the heavy hand of the state, and revolutions—even non-violent ones—have mixed outcomes. Speculation is rampant. Are events in Thailand just a little bit of history repeating or do they portend major change? Cogan asks.

Familiar Challenges in Thailand’s New COVID-19 Reality – Center for International Private Enterprise https://t.co/ax4PWV6uVW

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) September 17, 2020