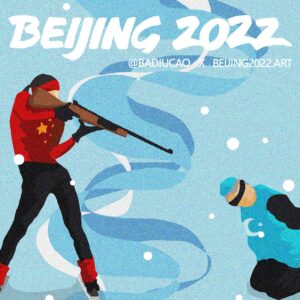

Credit: Badiucao

“Faster, higher, bossier” typifies China’s approach to the Winter Olympics, The Economist reports.

The Olympic movement has sold its soul by not challenging China on human rights abuses, observers suggest.

With the authorities tightening their grip across Chinese society, one major question is whether any Olympic participants, including athletes, will be willing or able to speak out on issues the government deems objectionable. Activists and human rights groups have accused the party of decimating civil liberties in Hong Kong, oppressing ethnic minorities in Xinjiang and Tibet, and censoring Peng Shuai, a top tennis player who has mostly disappeared from public view after accusing a senior Chinese leader of sexual assault, The New York Times reports:

Teng Biao, a Chinese lawyer who was detained and disbarred during the Beijing Olympics in 2008, said that he believed that visiting athletes had “a responsibility to say something” about China’s growing repression….. Xi is showing that China has become powerful enough that it does not need to worry about what people think, according to Mr. Teng, who went into exile and is now a visiting scholar at the University of Chicago.

Nobody left to lock up

“Compared to 2008, the Chinese government has become more and more powerful and aggressive. It seems they care less about international pressure,” he said. “They really want to pre-emptively silence the athletes,” said Teng [a recipient of the National Endowment for Democracy’s 2008 Democracy Award].

“There’s nobody left to lock up,” said Sophie Richardson, Human Rights Watch’s China director.

“There’s nobody left to lock up,” said Sophie Richardson, Human Rights Watch’s China director.

“Xi Jinping’s government has worked so assiduously since (China) was awarded these Games to just crush independent civil society,” she added. “Most people who could have or would have wanted to try to find ways to protest around these Games have already been arbitrarily detained, disappeared or driven in to exile.”

Victor Cha, who served in the White House under President George W. Bush and is the author of “Beyond the Final Score — The Politics of Sport in Asia,” said China’s moaning about others politicizing sports is “the pot calling the kettle black,” AP reports.

“There is no country that has ignored the Olympic Charter’s mandate to keep politics out of sports more than China,” Georgetown University’s and NED board member Cha wrote for the Center for Strategic & International Studies.

For the 2008 Summer Games, to mollify critics, the organizers pledged to “enhance all the social sectors, including education, medical care, and human rights.” That commitment fueled hopes that the event might become a catalyst akin to the 1988 Summer Games, in Seoul, which hastened South Korea’s transition from a dictatorship to a democracy, The New Yorker’s Evan Osnos writes.

Artworks satirizing China’s attempts to gloss over human rights abuses will be displayed in several Czech cities this week, in a provocative gesture on the eve of the Beijing Winter Olympics, The [London] Times reports. The five posters, designed by Badiucao, an exiled graphic artist, depict an ice-hockey player bludgeoning a Tibetan monk and a Chinese curler releasing the coronavirus instead of a stone.

‘Fascistic’?

How should we describe China’s political regime?

Credit: Badiucao

Taken together, “authoritarian” — used to also describe declining democratic states such as Hungary and Turkey — hardly feels enough, nor does it feel accurate, says Berlin-based journalist Melissa Chan. That is a disservice to the public. Journalists, politicians and others should consider calling elements of the Chinese state fascistic, if they are not entirely comfortable describing the state writ large as fascist.

The respected Chinese legal scholar Teng prefers calling the country totalitarian. But consider the hallmarks of fascism: a surveillance state with a strongman invoking racism, nationalism and traditional family values at home, while building up a military for expansion abroad, Chan writes for The Post.

Steven Butler, Asia program coordinator of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), summed up the concern of media groups ahead of the games: “Can China and the International Olympic Committee maintain a ‘bubble’ of total press freedom inside China’s vast sea of repression?” Butler asked, referring to the detention and forced labor of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, the dismantling of civic space in Hong Kong, massive surveillance of citizens, and the persecution of journalists and human rights defenders.

Sarah Cook, China Media Bulletin director of Freedom House, warned against information restrictions that Beijing authorities might impose on athletes, journalists, and visitors, including:

- Surveillance of athletes and journalists

- Reprisals for political speech and independent reporting

- Rapid censorship of any scandals, even those unrelated to the Olympics

- Stonewalling foreign journalists

- Repercussions after the closing ceremony

Amb. Derek Mitchell, of the National Democratic Institute, and Dr. Dan Twining, of the International Republican Institute, join the Hoover Institution’s Michael R. Auslin to talk about democracy in Asia, the China challenge, and predictions for 2022.

1/5 【Badiucao Art X @hrw】

The first of my 5 animation series on protesting #Beijing2022

The 2022 Beijing Olympics—by which Beijing hopes to “sportswash” its abysmal rights record—reflect Xi Jinping’s assault on human rights since coming to power. #CrimesAgainstHumanity pic.twitter.com/CMytc0iJXE

— 巴丢草 Badiucao💉💉 (@badiucao) January 19, 2022