Algerians took to the streets on Tuesday with renewed calls for 82-year-old President Abdelaziz Bouteflika to step down and not seek any more time in office when the country votes on April 18 (HT: Foreign Policy). Bouteflika’s offer of a new constitution and a truncated next term does not appear to have satisfied protesters, who faced off with riot police overnight, the AP adds:

Algeria sees frequent localized protests over tangible concerns like sewage or housing — problems the government can solve by spending money to fix them. When neighboring Tunisia and Libya overthrew autocratic leaders in 2011, Algeria avoided a mass Arab Spring uprising by boosting public spending to address economic concerns.

“What’s different now is that this is about the expression of political will,” said Geoff Porter of North African Risk Consulting. “The government can’t respond to this by spending resources.”

Algerians believe that political power in the gas-rich North African country is being wielded by a shadowy clique of civilian and military figures around the president, including powerful businessmen and Mr Bouteflika’s brother. The protesters view the Bouteflika candidacy as a cynical attempt by this coterie to keep hold of the levers of power, the FT’s Heba Saleh writes.

For the public, the decision to go for a fifth term has been made by the military, which is taking advantage of a weak president, argues Lahouari Addi, emeritus professor of sociology at the Institut d’Études Politiques (Sciences-Po) in Lyon, and author of Radical Arab Nationalism and Political Islam. It is indeed the idiosyncrasy of the Algerian system to have formal power embodied by the president and the government, while real power is in the hands of the military leadership. The street is rebelling against the control of institutions by the military. Who will be the winner? The future of democracy and the rule of law in Algeria is at stake, he tells Carnegie’s Michael Young.

“We do not know who is running the country,” said Moustapha Bouchachi, a prominent Algerian human rights lawyer. “Who is appointing governments, ambassadors and ministers? There are people making decisions in this country without official positions and without accountability.”

“We do not know who is running the country,” said Moustapha Bouchachi, a prominent Algerian human rights lawyer. “Who is appointing governments, ambassadors and ministers? There are people making decisions in this country without official positions and without accountability.”

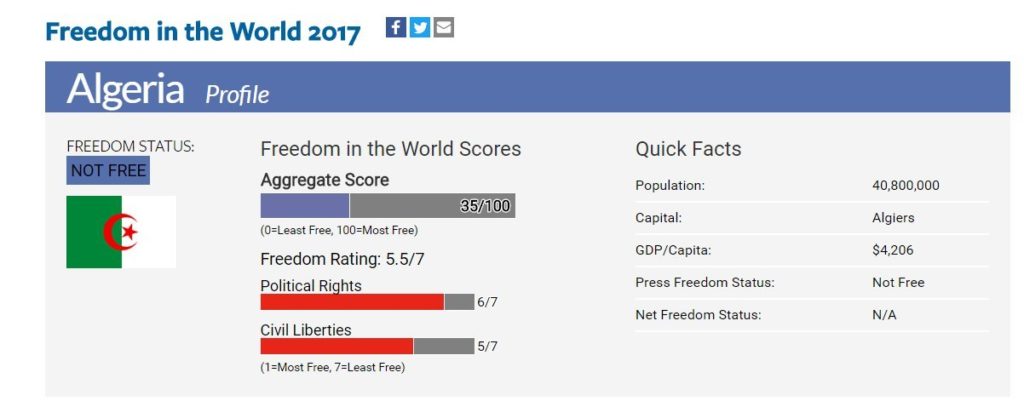

Algeria is deemed Not Free by Freedom House, the democracy and human rights watchdog.

Protesting is illegal in Algeria, but the demonstrations—which began on February 21—swelled over the weekend, says the Project on Middle East Democracy [POMED – a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy]:

Tens of thousands of Algerians turned out in Algiers and many other cities, including Oran, Setif, Bouira, Tizi Ouzou, and Boufarik; thousands also turned out in France to support the protesters in Algeria. While the protests have been peaceful and security forces have largely exercised restraint, Magdalena Mughrebi, Amnesty’s Middle East and North Africa deputy director, appealed to the Algerian authorities to “respect the rights of demonstrators, and not to use excessive or unnecessary force to quell peaceful protests.”

“For months, there’s been speculation that the elites would make some kind of effort to find a successor to Bouteflika, but the announcement that he would run again was widely interpreted as a sign of a failure to do so,” said POMED’s Stephen McInerney. “It seems there was only consensus around keeping Bouteflika and fears that moving on would disrupt the status quo that le pouvoir is happy with,” he told the Guardian.

“For months, there’s been speculation that the elites would make some kind of effort to find a successor to Bouteflika, but the announcement that he would run again was widely interpreted as a sign of a failure to do so,” said POMED’s Stephen McInerney. “It seems there was only consensus around keeping Bouteflika and fears that moving on would disrupt the status quo that le pouvoir is happy with,” he told the Guardian.

To push for five more years as president of a wheelchair-bound octogenarian who has not spoken publicly in years underlined how they had failed to come up with a viable alternative they trusted to protect their interests, said Dalia Ghanem Yazbeck, resident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut. “This is not just about Bouteflika,” she told the FT. “This is about the entwined interests of an entire clan, his brothers, people from his region, the business elite. The protests are putting in jeopardy an entire system, including the interests of some in the military and the governing National Liberation Front party.”

Critics of the Algerian government said concessions announced on Sunday were too little, too late, the NY Times adds.

“The youth today don’t want a fifth term,” Omar Belhouchet, the editor of the fiercely independent El Watan newspaper, said in a telephone interview from Algiers. “They are fed up with this authoritarian regime which is stifling people, which is pushing its own citizens to die in the Mediterranean.”

“The whole political system needs to be changed,” he added.

Thousands more staged new anti-government protests on Monday in the capital and other cities, including Oran, Constantine and Bouira, according to witnesses and local TV footage, Al Jazeera adds.

Thousands more staged new anti-government protests on Monday in the capital and other cities, including Oran, Constantine and Bouira, according to witnesses and local TV footage, Al Jazeera adds.

“These demonstrations showed that the Algerian population is not naive. We do not believe President Bouteflika when he says that he is ready to step down in the near future. It is a new manoeuvre of the regime to find a way to buy time,” said Reda Boudraa, deputy leader of Rally for Democracy and Culture (RDC), a secular opposition party.

“What is interesting with his message is that he is acknowledging that something new is happening with these protests and that his regime can no longer survive without any change,” he added.

France has remained conspicuously silent as Bouteflika, a veteran of Algeria’s independence struggle, stares down a wave of angry protests opposing his bid for a fifth term as president. And with good reason, say some experts, RFI reports:

Algeria is the largest country in Africa, and it holds the key to the security of the north-west. While France’s own problems with social movements – ie the gilets jaunes, or Yellow Vests – make it hard for Paris to adopt an official position (France has to be seen to be supporting democracy), [French historian Tramor] Quemeneur says the real reason for Macron’s silence is to do with security and fighting terrorism.

“France has a close relationship with the Algerian regime, and the Algerian regime plays an important role in the Maghreb and in all of North Africa – including the Sahel,” he says. “Algeria is crucial to the Sahel’s defence and security, so a big political change could pose problems for France as well – and for the fight against jihad.”

Hybrid regime

“Algeria lives, so to speak, under modern authoritarianism, which blends authoritarian and some democratic elements,” said political scientist Rachid Ouaissa of the University of Marburg. “I wouldn’t say there is a dictatorship in Algeria – those days are over. The country lives under a rigid bureaucracy that is mentally still stuck in the 1970s,” he told Deutsche Welle.

Will peaceful protest be enough to shift the balance of power in Algeria? The future of the movement is uncertain, yet a fifth term for Bouteflika is clearly unthinkable for many citizens, Ghaliya Djelloul of the Catholic University of Louvain writes for the Conversation.

After initially breaking out on 22 February, the demonstrations continued two days later, building on an earlier call to protest from civil society group Mouwatana (Citizenship), notes analyst Andrew Lebovich. In his book La Martingale Algérienne, Abderrahmane Hadj Nacer observes that Algeria has only ever engaged in real political, social, and economic reforms in times of crisis, he writes for the European Council on Foreign Relations:

Such a crisis is here for the world to see. The Algerian citizens who have poured onto the streets, and the political and security actors who are trying to keep up, will decide whether the crisis deepens. For now, no one knows how Algeria’s leaders will attempt to deal with the ongoing protests and whether the current proposals will be enough.

Hannah Armstrong, an analyst at the International Crisis Group think-tank, cautioned against a tendency to “over-emphasise the role of the generals” in Algeria under Mr Bouteflika, the FT adds. “During the course of Bouteflika’s fourth term there were purges of generals and within the police of various figures considered not to be completely compliant with the vision of the regime,” she said. “The army and intelligence services are still important but not as an autonomous pole of power.”