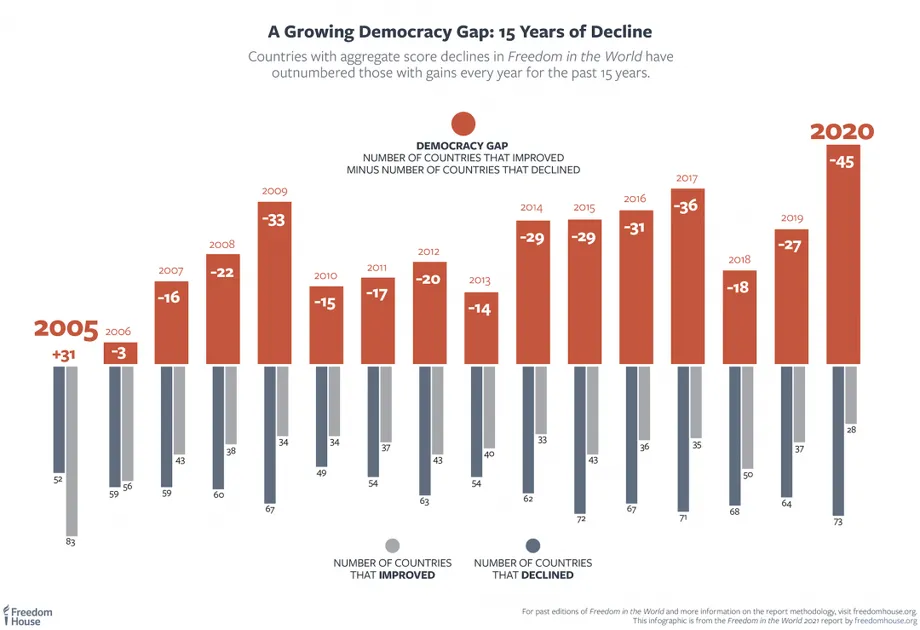

One reason many countries were willing to embrace democratic models was the success of the US and other Western nations in the 20th century. But if democracy no longer looks like a successful model — and keeps backsliding — that source of inspiration will dim, VOX’s German Lopez observes.

A new political force called We Continue the Change (PP) is the surprise winner of Bulgaria’s third parliamentary election in a year. Led by two energetic businessmen, Harvard graduates Kiril Petkov and Assen Vassilev, it won 67 of the parliament’s 240 seats, Vessela Tcherneva writes for the European Council on Foreign Relations. @vtcherneva But Bulgaria is not alone in experiencing a degree of democratic renewal, she adds:

In Hungary, parties have come together in a new coalition of six parties to remove the prime minister, Viktor Orban, who has ruled the country for over a decade and captured the state. In the Czech Republic, it took a five-party coalition to finally eject Andrej Babis after he had spent two terms in power. In Serbia, Aleksandar Vucic has become the epitome of ‘unreplaceable government’, and the divided opposition has been contributing to that prophecy.

Central Europe’s illiberal and authoritarian actors have demonstrated a great ability to learn from each other ways to significantly enhance their toolkit for undermining checks and balances, dividing society, and suppressing vulnerable groups, says analyst Daniel Hegedüs. In contrast, pro-democracy actors—who in the 1990s and early 2000s pioneered transnational policy learning in the region—have been unable to convert their exchanges into any meaningful domestic political resources. There are three broad explanations for this, he writes for the German Marshall Fund:

Central Europe’s illiberal and authoritarian actors have demonstrated a great ability to learn from each other ways to significantly enhance their toolkit for undermining checks and balances, dividing society, and suppressing vulnerable groups, says analyst Daniel Hegedüs. In contrast, pro-democracy actors—who in the 1990s and early 2000s pioneered transnational policy learning in the region—have been unable to convert their exchanges into any meaningful domestic political resources. There are three broad explanations for this, he writes for the German Marshall Fund:

- First, with Western democracy assistance coming to a halt after the countries in the region joined the EU between 2004 and 2011, and as there was neither EU conditionality nor dedicated funds to support it, the culture of transnational democratic policy learning slowly evaporated in Central Europe.

- Second, the direction of democratic policy learning became unclear. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Western countries provided their experiences, institutional solutions, and democracy assistance to the emerging democracies of Central Europe. Today, such an approach to policy learning does not necessarily make sense anymore. Even if certain older democracies, like the United States, have experienced the rise of illiberal populism, they have been unable to find effective and sustainable social and political responses. There is barely any relevant best practice they can share.

- Third, and perhaps most important, the policy learning illiberal actors have successfully used and the one pro-democracy actors need is different. The main policy learning of authoritarian actors is instrumental, focused on legislative solutions, acquisition of media outlets and other key assets, organizational patterns, and campaign strategies, which are easily transferable and simple to implement when in power.

From blocking websites to forcing companies to share user data, governments – including democracies – are increasingly resorting to “authoritarian” methods to control the internet, tech experts warned on Thursday. Governments like China and Russia are blocking social media content, requiring firms to submit to data surveillance, and silencing journalists and activists online, panelists told the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s annual Trust Conference.

From blocking websites to forcing companies to share user data, governments – including democracies – are increasingly resorting to “authoritarian” methods to control the internet, tech experts warned on Thursday. Governments like China and Russia are blocking social media content, requiring firms to submit to data surveillance, and silencing journalists and activists online, panelists told the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s annual Trust Conference.

“The digital world is increasingly moving into an authoritarian space,” said Alina Polyakova, head of the Center for European Policy Analysis, a US-based think-tank.

Those threats are coming from the Western world too, said Javier Pallero, policy director of advocacy group Access Now. “A lot of democratic governments are now acting as authoritarians… it’s not just the Russias and Chinas of the world,” he added, citing police use of facial recognition in the United States and street surveillance in Argentina.

We are living at a time of authoritarian encroachment on civic space in which ‘democracy promotion’ is mistakenly conflated with military occupation and/or coercive regime change, according to Stanford University’s Larry Diamond.

It is a mistake to argue that the principal goals in Afghanistan and Iraq were reflective of democracy promotion. Democracy promotion involves the use of peaceful assistance at first, and partnerships and diplomacy, to try to encourage and support democratic change and institutionalization of constitutional mechanisms in a civil society, he told Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN).

There are at least three approaches that have played a crucial role in political dynamics that contained illiberal developments in Central Europe in recent years, and that should be learned and applied across the region, adds Hegedüs, a visiting fellow at the German Marshall Fund:

There are at least three approaches that have played a crucial role in political dynamics that contained illiberal developments in Central Europe in recent years, and that should be learned and applied across the region, adds Hegedüs, a visiting fellow at the German Marshall Fund:

- First, electoral cooperation between civil society and democratic parties. This pattern emerged during the 2019 municipal elections in Hungary and the 2019 presidential and 2020 parliamentary elections in Slovakia. These polls demonstrated that CSOs can play a crucial role in candidate nomination, mobilization, and campaigning, and that they can also provide higher legitimacy and extra mobilization resources for the democratic actors they ally with….

- Second, successful mobilization of diasporas. This was perfected by Romania’s pro-democracy forces with the diaspora playing a crucial role in the 2018 anti-corruption movement and the 2019 presidential election. Diaspora mobilization also had some sporadic forms and positive impact during the December 2018 labor code protests in Hungary. ….

- Third, reframing elections as referenda on autocratizing leaders. This can be labeled “good polarization.” Polarization is often perceived as a negative phenomenon that undermines the stability of established democracies. This might be well true, but it can also bring down autocratizing regimes. ….

The solution to protect online spaces and users is to redistribute power in the hands of people, Thomson Reuters panelists said – but as groups rather than individuals:

The solution to protect online spaces and users is to redistribute power in the hands of people, Thomson Reuters panelists said – but as groups rather than individuals:

Community internet or decentralised networks – where communication services are localized rather than monopolized by government or corporate giants – give users more control over their data and privacy, researchers say.

“We place too big a burden on individuals to make complex decisions about what to do with their data, how algorithms work,” said CEPA’s Polyakova. “Most of us, for example, are constantly asked whether to accept or reject cookies, and we click through without understanding.”

Democratic renewal in Europe: Bulgaria joins a growing trend: https://t.co/qK8Qvck43w via @ecfr

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) November 19, 2021