As Saied steers #Tunisia toward a national dialogue & constitutional referendum that critics say may cement his authoritarian rule, pressure is growing on him to fulfill his pledge. https://t.co/SbbYhuZb1t

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) January 3, 2022

As President Kais Saied steers Tunisia toward a national dialogue and constitutional referendum that critics say may cement his authoritarian rule, pressure is growing on him to fulfill his pledge. The question is whether he can, Vivian Yee writes for The New York Times:

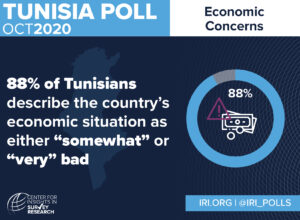

Already deeply indebted and running a large deficit after years of mismanagement and the pandemic, the government recently announced that it expected to borrow nearly $7 billion this year. For that, Tunisia must turn to international lenders including the International Monetary Fund, which has demanded painful austerity measures. Those could cut into the wages of a broad swath of Tunisians and slash government subsidies just as the price of electricity and basic food items is climbing — a formula that could lead to protests and mass unrest.

“It’s going to be a very painful year,” said Tarek Kahlaoui, a Tunisian political analyst. “It’s going to be unpopular no matter what.”

Tunisia was the only democracy to emerge from the Arab Spring revolts of a decade ago, but civil society groups and Saied’s opponents have expressed fear of a slide back to authoritarianism a decade after the revolution that toppled longtime dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, AFP reports.

Tunisia was the only democracy to emerge from the Arab Spring revolts of a decade ago, but civil society groups and Saied’s opponents have expressed fear of a slide back to authoritarianism a decade after the revolution that toppled longtime dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, AFP reports.

“The country is wallowing in political uncertainty, even after Saied announced his roadmap, which doesn’t seem to have reassured partners either domestically or internationally,” said analyst Hamza Meddeb. “There are many questions marks over the reliability of this process.”

The consultations will begin “amid socio-economic unrest, with questions regarding freedoms” and “repression in disguise,” he told AFP.

Saied has long dreamed of remaking Tunisia as an indirect democracy. Now he has arrogated to himself the power to do so [and his] obsession at least seems rooted in sincere belief, The Economist adds:

For most Tunisians, though, a new constitution ranks low on their list of priorities. Voters are more concerned about a sluggish economy and an 18% unemployment rate. A growing pile of debt (now 88% of GDP) threatens to push the country into insolvency. Tunisia can ill afford a year of inaction—yet the president, like the elected parliament he suspended, seems to have few ideas for fixing the economy.

For most Tunisians, though, a new constitution ranks low on their list of priorities. Voters are more concerned about a sluggish economy and an 18% unemployment rate. A growing pile of debt (now 88% of GDP) threatens to push the country into insolvency. Tunisia can ill afford a year of inaction—yet the president, like the elected parliament he suspended, seems to have few ideas for fixing the economy.

It is not clear that outside powers can exercise the kind of clout that some Washington think tanks envision, argues Daniel Brumberg, Director of Democracy and Governance Studies at Georgetown University, and a Senior Non-Resident Fellow at the Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED).

The problem is not merely that Saied has used outside pressures to discredit his domestic critics. The more basic issue is that opposition leaders must still tackle the one major challenge that they have skirted for some eight years, namely: how will they square the quest for a pluralistic democracy with the simultaneous pursuit of both market reforms and social justice? If Saied’s opponents want to take the wind out of his sails, they must first unify behind a realistic road map that points the way to a new democratic bargain, he writes for the Arab Center:

This much needed partnership with the international community will have no chance of emerging unless Tunisia’s leaders muster the political will to replace a consensus-based power-sharing democracy, which had produced a nearly paralyzed parliament, with a reinvigorated democracy—one that assigns real legislative authority to a government derived from an elected majority. President Saied seems resolved to prevent a revitalization of parliamentary democracy by imposing a presidential system in which the will of the people will presumably prevail through a strong executive backed by a compliant judiciary, legislature, and military.

ICDR Statement on the recent anti-democratic actions in Tunisia

The allure of this kind of populist project endures because many Tunisians view democracy as little more than a corrupt enterprise that has only enriched a narrow elite, adds Brumberg, a contributor and editorial board member of the NED’s Journal of Democracy. RTWT

But analysts said it was unclear how transparent the consultation process would be, since the government had not announced whether the results would be public or how they would influence the new constitution, which is to be drafted by a commission appointed by Mr. Saied, The Times adds.

“I think it’s just a way to legitimize the decision they’re already going to make,” said Mohamed-Dhia Hammami, a Tunisian political researcher and analyst.