The United States has lost influence to China in Southeast Asia over the past five years, a leading Australian think-tank said today. According to a report released by Sydney’s Lowy Institute, China has increased the overall margin of its influence in Southeast Asia, while making inroads into areas that have traditionally been American strengths, The Diplomat’s Sebastian Strangio writes:

The United States has lost influence to China in Southeast Asia over the past five years, a leading Australian think-tank said today. According to a report released by Sydney’s Lowy Institute, China has increased the overall margin of its influence in Southeast Asia, while making inroads into areas that have traditionally been American strengths, The Diplomat’s Sebastian Strangio writes:

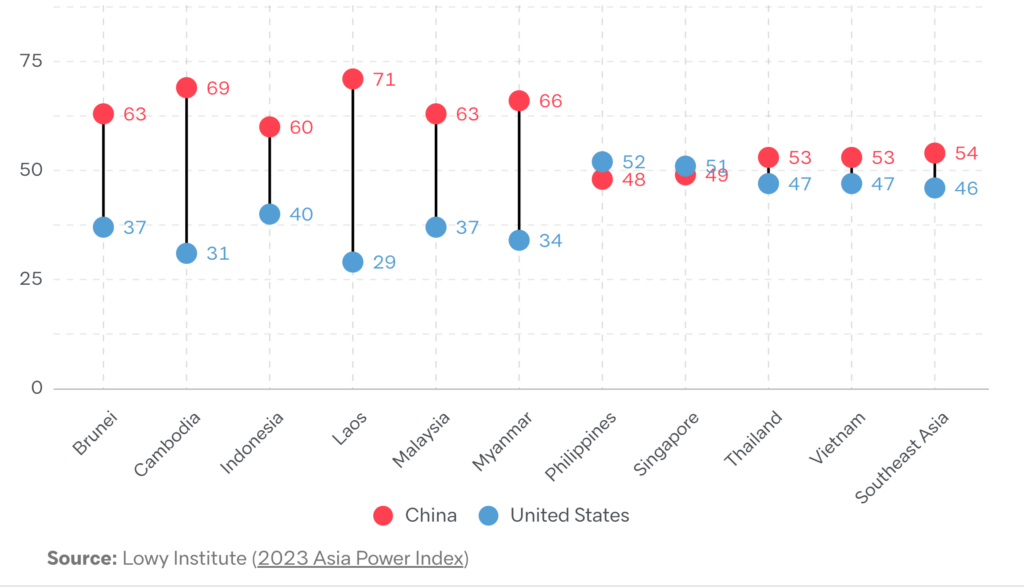

The new report showed that in 2018, China led the U.S. 52–48 for influence in the region. In 2022, this lead increased to 54–46. The U.S. remains more influential than China in just two nations – the Philippines and Singapore– and even then, by relatively narrow margins: 52–48 in the former case, and 51–49 in the latter. This is down from three nations (Singapore, Vietnam, and the Philippines) in 2018, and one nation (Thailand) in which it was equally influential to China.

Lowy’s annual Asia Power Index “measures resources and influence to assess the relative power of states in Asia” and gauges influence in four categories – economic relationships, defense networks, diplomatic influence, and cultural influence – each of which is assigned a rating out of 100.

Lowy’s annual Asia Power Index “measures resources and influence to assess the relative power of states in Asia” and gauges influence in four categories – economic relationships, defense networks, diplomatic influence, and cultural influence – each of which is assigned a rating out of 100.

“Clearly there is a competition for influence in Southeast Asia, and the balance is shifting noticeably towards China,” the Lowy Institute’s Susannah Patton told the Australian Financial Review. While the U.S. and China were not the only powers in Southeast Asia, she added, they “are the most important external influences and the direction of travel is not positive for the U.S.”

China has two repressive systems that exist simultaneously: the highly coercive and surveilled system in Xinjiang, and the trust-based model of everyday repression prevalent throughout the rest of the country, argues Lynette H. Ong, professor of political science at the University of Toronto, and the author of Outsourcing Repression: Everyday State Power in Contemporary China (2022).

The latter model has undergirded grassroots governance in China and facilitated the routine implementation of Zero-Covid, she writes for the Journal of Democracy:

The latter model has undergirded grassroots governance in China and facilitated the routine implementation of Zero-Covid, she writes for the Journal of Democracy:

Drawing on a protest event dataset, I analyze the key characteristics of the covid protests erupted in November and December of 2022, before situating them in the larger context of China’s political future under Xi Jinping’s rule. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has responded to the the covid protests erupted in November and December of 2022with a combination of concession and repression. But neither the carrot nor the stick is able to fundamentally address the deep-rooted social problems or halt the tide of dissent.

Coupled with structural economic challenges, these protests could be the harbinger of a new era of contentious state-society relations in China, the seeds of which were sown years ago–only precipitated and underscored by the CCP’s Covid debacle, Ong asserts.

Minxin Pei

Minxin Pei, a professor at Claremont McKenna College who studies Chinese politics, said it is possible that Beijing will re-engage with Washington once it feels it has more leverage, The New York Times reports. That could come after Beijing has deepened ties with more nonaligned countries like Brazil or after it has widened splits in Europe over how closely to follow the United States in its tougher stance toward China.

“China wants to engage the U.S. from a position of strength, and China is clearly not in that position now,” Mr. Pei said. “If anything, America’s success in rallying allies and waging the tech war against China proves that it is still far more powerful than China and has more tools at its disposal.”

The House Foreign Affairs Committee this week hosted a hearing (below) with witnesses: Ambassador Andrew Bremberg, President Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation; Mr. Bob Fu, President China Aid Association; Mrs. Geng He, Wife of Mr. Gao Zhisheng; Mrs. Sophie Luo, Wife of Mr. Ding Jiaxi; Mrs. Yaqiu Wang, Senior China Researcher, Human Rights Watch; Mr. Thomas Kellogg, Executive Director, Georgetown University Center for Asian Law.

The @HooverInst hosted the United States House Select Committee on Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party. The bi-partisan delegation participated in an intensive day-and-a-half of programming with Hoover’s experts: https://t.co/cssaeMwOS7

— Hoover Institution (@HooverInst) April 21, 2023