Many Colombians, tired of the country’s prolonged period of polarization, hoped this would be the year things changed, according to Theodore Kahn and Sylvana Amaya, senior analysts in Control Risks’ Global Risk Analysis practice. Ahead of presidential elections in May, efforts by erstwhile centrist rivals to unite behind a single candidate looked uniquely promising, they write for Americas Quarterly:

The Center Hope Coalition – an alliance of centrist and center-left politicians from different parties and independent movements formed last June – have touted their “strength through differences” and made rejecting the extremes a campaign platform. But as quickly as hope came, it seems to have evaporated. After two weeks of defections, recriminations and infighting within the Coalition, unity in 2022 looks increasingly out of reach. And a run-off between populist candidates on the left and right– in the vein of similarly divisive elections in 2018 – more likely.

In the spring of 2021, Colombians took to the streets to vent pent-up frustrations. What was behind the unrest? AS/COA Online asks.

“This whole cocktail of global economic decline, poor government, plus Covid, put an end to this growth [from the past decade], and people are very unsatisfied with inequality, with the corruption, with the lack of providing basic services,” Muni Jensen, a political analyst and senior advisor with the Albright Stonebridge Group, tells AS/COA’s Holly K. Sonneland. While the protests have since subsided, the discontent continues to simmer as the country heads into a big electoral season.

“This whole cocktail of global economic decline, poor government, plus Covid, put an end to this growth [from the past decade], and people are very unsatisfied with inequality, with the corruption, with the lack of providing basic services,” Muni Jensen, a political analyst and senior advisor with the Albright Stonebridge Group, tells AS/COA’s Holly K. Sonneland. While the protests have since subsided, the discontent continues to simmer as the country heads into a big electoral season.

Ingrid Betancourt was campaigning to become the first female president of her native country when she and her entourage encountered a checkpoint manned by a group of rebels belonging to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) movement on February 23, 2002 in a remote corner of southwestern Colombia, Al Jazeera reports:

Fast forward to today. The now 60-year-old Betancourt announced her decision last month to seek the nation’s highest office for a second time as a leading light in a recently formed coalition of Colombia’s centrist political parties. During a speech at a hotel in the national capital of Bogota to launch her presidential bid, the former hostage pledged to crack down on the country’s chronic corruption and cast herself as the candidate of reconciliation who can bridge the deep divisions polarising millions of Colombians.

Some political analysts have described Betancourt’s go-it-alone approach as a non-starter and express concerns that her very public divorce from the Centro Esperanza coalition may have inflicted irreparable harm on its own prospects for making it into a second-round runoff vote later this year, Al Jazeera adds,

Some political analysts have described Betancourt’s go-it-alone approach as a non-starter and express concerns that her very public divorce from the Centro Esperanza coalition may have inflicted irreparable harm on its own prospects for making it into a second-round runoff vote later this year, Al Jazeera adds,

“The damage she has done is great,” said former National Endowment for Democracy Reagan-Fascell fellow Laura Gil, director of Diálogos and Estrategias, a Bogota-based firm dedicated to supporting human rights, reconciliation, and post-conflict reconstruction. “I’m not sure the coalition will recover from this.”

The U.S.-Colombia Strategic Alliance Act of 2022 will recognize the special relationship our nations have built and formally designate Colombia as a “Major Non-NATO Ally” of the United States. It will be ambitious in establishing a renewed emphasis on human rights, labor rights and security cooperation, says Sen. Bob Menendez, who today hosted a US Senate foreign Relations Committee hearing on Reinvigorating U.S. – Colombia Relations. As important, the bill will reinforce the United States’ support for a full-throated implementation of the 2016 Peace Accord, which continues to be the best — albeit imperfect — tool to build peace and democratic governance in Colombia, he writes for The Miami Herald.

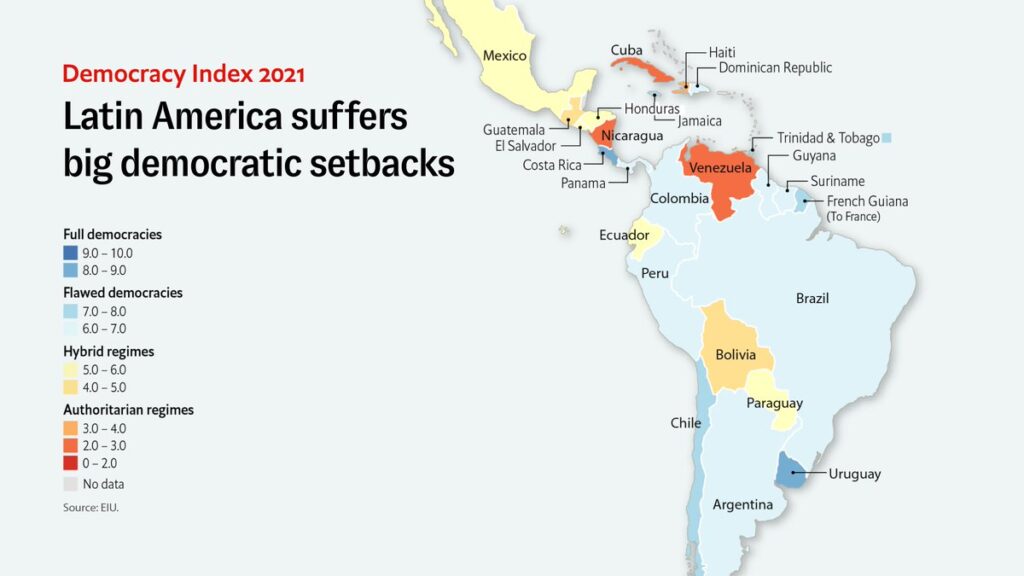

it is imperative that Colombia avoids the autocratic trajectory seen in Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Cuba, the Senate hearing was told.

“An acute priority is collaborating with Colombia to fend off the malign activities of state and

non-state actors, who increasingly seek opportunities to erode the hemispheric consensus on the importance of the rule of law and democratic governance,” said Ambassador Brian A. Nichols, Assistant Secretary of State in the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs. “Those actors helped Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Cuba turn away from this consensus – and enable the autocratic leaders of those countries to hold on to power by suppressing their own people.”

Marcela Escobari, USAID Assistant Administrator for Latin America and the Caribbean commended Colombia for its dramatic turnaround.

“Once a nearly failed state, the country has come back from the brink to establish itself as a stable democracy, Latin America’s fourth largest economy and a close U.S. partner and ally,” she said. However, she told the hearing: “Social and environmental leaders – the voice of peaceful advocacy for the democratic rights of rural communities – have become even more vulnerable to violent attack.”