Jan. 6 gave the world’s democracies a glimpse of their own mortality, notes NATO secretary-general Anders Fogh Rasmussen. But it can also be a catalyst for revival, he writes for Foreign Policy.

But President Joe Biden’s personnel choices have given hope to those observers who reject the notion that democracies are either losing out to autocratic rivals or required to perfect democracy domestically before advocating it abroad.

“Biden has chosen people who understand and are committed to strategic competition,” said Thomas Wright, a foreign-policy expert at the Brookings Institution. “I’ve never understood the trade-off between ambition at home and ambition overseas,” he said. “It’s precisely because democracy is challenged at home that the U.S. needs to be more energetic in defending democracy overseas.”

The best way for America to promote democracy and human rights is to lead by “the power of our example,” as Biden underlined in his inaugural address. Doing so would enable America to regain the “soft power” that has historically represented one of the main pillars of its international influence, according to Javier Solana, a former EU high representative for foreign affairs and security policy, and Eugenio Bregolat, an EsadeGeo Senior Fellow and the author of The Second Chinese Revolution.

The best way for America to promote democracy and human rights is to lead by “the power of our example,” as Biden underlined in his inaugural address. Doing so would enable America to regain the “soft power” that has historically represented one of the main pillars of its international influence, according to Javier Solana, a former EU high representative for foreign affairs and security policy, and Eugenio Bregolat, an EsadeGeo Senior Fellow and the author of The Second Chinese Revolution.

It is vital that US promotion of democracy and human rights – on which Biden is wise to insist – is carried out in a calm, consistent, and sensible manner. Efforts to safeguard liberal democracy are essential, as are those aimed at preventing serious human-rights violations. But this is different from trying to impose values or enforce conduct through “regime change,” they write for Project Syndicate, adding that the US will not demonstrate real commitment to these values by wielding them opportunistically or selectively.

Incoming Democratic officials confirmed a bipartisan consensus about the mounting challenge to the United States from China, the Post adds. Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines pledged to Sen. Ben Sasse (R-Neb.) to “make it a priority from my perspective to make sure we are allocating the right resources” to it.

But the U.S. “will not be able to compete globally—especially against China’s pursuit of international legitimacy for its model of governance and development—unless we are able to make our version of democracy and capitalism successful and appealing again,” analyst Paul Heer writes for the National Interest.

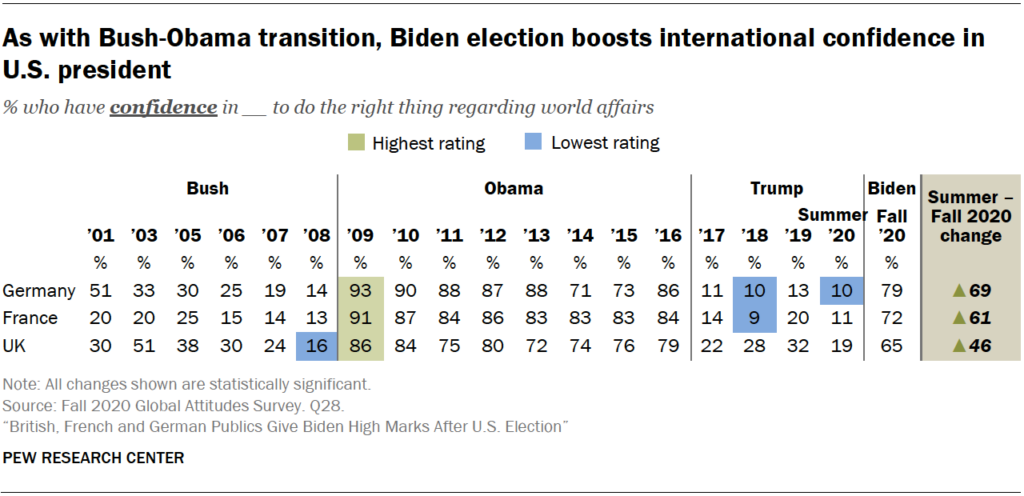

Even before the violent storming of the U.S. Capitol in early January, there were widespread concerns about the health of U.S. democracy among three of America’s closest allies, a new Pew Research Center survey finds: 73% of Germans, 64% of the French and 62% of the British think the U.S. political system needs to be subject to either major changes or completely reformed. (See “Even before riot at Capitol, most people in Germany, France and the UK had concerns about U.S. political system” for more on this question, as well as other findings on attitudes regarding the health of American democracy.)

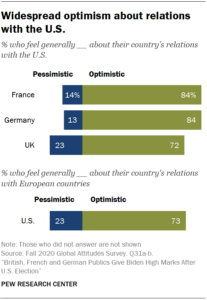

But survey respondents in all three countries express confidence in Biden and optimism that relations with the U.S. will improve, and there are few significant ideological differences between the left and the right, Pew adds:

But survey respondents in all three countries express confidence in Biden and optimism that relations with the U.S. will improve, and there are few significant ideological differences between the left and the right, Pew adds:

He receives roughly the same positive reviews among people who place themselves on the left, center and right of the political spectrum. However, Biden generally gets somewhat lower ratings from supporters of right-wing populist parties. For example, just 51% of Germans with a favorable view of Alternative for Germany (AfD) have confidence in Biden, compared with 84% of those with an unfavorable opinion of the party. Smaller but still significant differences exist between supporters and non-supporters of the Brexit Party (now called Reform UK) in the UK and National Rally in France. (See appendix for more information on European populist parties.)