The populist parties now making headway in many Western democracies are fundamentally different from the “anti-system” parties of the interwar years, which openly denounced democracy, argues Jørgen Møller, who teaches in the Department of Political Science at Aarhus University in Denmark. Indeed, there are no parties of note in any of the Western democracies that aim to introduce an alternative system to the democratic one—as we did see as recently as the 1970s and 1980s.

The populist parties now making headway in many Western democracies are fundamentally different from the “anti-system” parties of the interwar years, which openly denounced democracy, argues Jørgen Møller, who teaches in the Department of Political Science at Aarhus University in Denmark. Indeed, there are no parties of note in any of the Western democracies that aim to introduce an alternative system to the democratic one—as we did see as recently as the 1970s and 1980s.

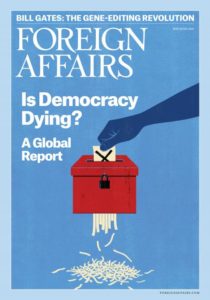

A spate of books* on the challenges facing today’s democracies are testimony to what Aviezer Tucker has termed “the disillusioned political zeitgeist of the second decade of the 21st century” have at least two other things in common, he writes for The American Interest:

-

First, they issue stern warnings that even established democracies in Western Europe and North America face grave dangers due to the rise of populism out of the “Great Recession” that began in 2008.

First, they issue stern warnings that even established democracies in Western Europe and North America face grave dangers due to the rise of populism out of the “Great Recession” that began in 2008. - Second, they turn to history in general and the interwar period in particular for parallels, and they use these parallels to argue that present-day democracies are more fragile than we like to believe.

- And perhaps they have a third characteristic in common: They make historical analogies that are mainly false.

The place to look for historical insights about how well-established democracies respond to crisis is to scrutinize what happens in this kind of regime when crises hit, adds Møller. If we do this, the historical lesson that emerges is much more heartening: Old democracies are remarkably stable even in the face of crises as devastating as those of the interwar period.

There are probably many different reasons for this democratic resilience. One important factor is the experience with democracy itself…[but] lurking behind these learning and habituation mechanisms is the fact that well-established democracies have vibrant civil societies, he suggests:

As Alexis de Tocqueville pointed out in Democracy in America, civil society bolsters democracy by creating a bottom-up bulwark against transgressions by the powers that be. Civil society associations—which were already ubiquitous in the America Tocqueville visited in 1831-32—bind individuals together, increase their political involvement, and enable them to speak truth to power, thereby resisting the centralization of power that Tocqueville had seen in France in his own lifetime and that he so feared. Seymour Martin Lipset and his co-authors elaborated these ideas in their seminal Union Democracy, published in 1956, in which they argued that democracy can only become institutionalized where voluntary associations provide information to citizens, school them in democracy, and allow them to oppose the cabals and maneuverings of would-be dictators.

As Alexis de Tocqueville pointed out in Democracy in America, civil society bolsters democracy by creating a bottom-up bulwark against transgressions by the powers that be. Civil society associations—which were already ubiquitous in the America Tocqueville visited in 1831-32—bind individuals together, increase their political involvement, and enable them to speak truth to power, thereby resisting the centralization of power that Tocqueville had seen in France in his own lifetime and that he so feared. Seymour Martin Lipset and his co-authors elaborated these ideas in their seminal Union Democracy, published in 1956, in which they argued that democracy can only become institutionalized where voluntary associations provide information to citizens, school them in democracy, and allow them to oppose the cabals and maneuverings of would-be dictators.

“This is not 1919, 1929, or 1933. Whatever challenges our democracies face today, they differ fundamentally from those of the interwar period,” Møller concludes. RTWT

*These books include Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt’s How Democracies Die: What History Reveals About Our Future, Madeleine Albright’s Fascism: A Warning, David Runciman’s How Democracy Ends, and the anthology Can It Happen Here? Authoritarianism in America edited by Cass Sunstein.

Jørgen Møller teaches in the Department of Political Science at Aarhus University in Denmark. Together with Agnes Cornell (Lund University) and Svend-Erik Skaaning (Aarhus University), he is writing a book entitled Democratic Stability in an Age of Crisis: Reassessing the Interwar Period.