Civil society has been left to face the Sudanese government alone

Since the successful removal of former president Omar al-Bashir, Sudan’s struggle for civilian rule has the world holding its breath, writes Julie Snyder, an adjunct fellow with the Human Rights Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. After finally reaching a transition deal with the Transitional Military Council (TMC), the Sudanese Freedom and Change Movement still faces a long road ahead on their path to democracy. Strikingly – though perhaps not surprisingly – it is Sudanese women who are leading the charge, accounting for more than 70 percent of protesters. As a result, women have become the face of the movement and taken on significant risks to organize, participate in, and lead protests.

In June, attacks on protesters left at least seven people dead and more than 180 injured. Sudanese women human rights defenders (WHRDs) in particular have been targeted by various security actors affiliated with the TMC. The Janjaweed – infamous for perpetrating mass rape among other atrocities – have once again weaponized sexual violence to silence women. With violations ranging from rape and murder to arbitrary detention, these gendered attacks on Sudanese WHRDs aim to silence women and snuff out the seeds of democracy.

MEMRI

Despite the dangerous conditions and threats to their own safety, Sudanese women have persisted in their protest, demonstrating incredible resilience. Even after reaching this agreement, there is a dire need for to protect, support, and amplify the efforts and specific needs of Sudanese WHRDs to promote a peaceful and sustainable democratic transition.

When women participate meaningfully in peace processes, they are far less likely to fail and more likely to last. Two women were included in the 10-person negotiating committee with the TMC. This inclusion – though not enough – is a promising step forward; under President Bashir’s regime, there were no cabinet positions filled by women and only 25 percent of parliamentary seats reserved for women, mostly as placeholders for their husbands. Women’s rights in Sudan are heavily suppressed, ranging from strict public order laws dictating dress to secret, arbitrary detention.

Research suggests that countries with strong gender equality are more resilient and more prosperous. Yet WHRDs almost always are the first and worst targeted in times of conflict. Attacks against WHRDs are fueled by a number of factors, such as entrenched discriminatory gender norms, a distinct lack of legal protection, and allegations of operating under foreign influence. And the uncertainty of Sudan’s future means that they need even more support. Civic space is highly regulated, making it difficult for international civil society to lend support. Furthermore, the government still finds itself on the US list of state sponsors of terrorism, heavily restricting funding for civil society. Though lifted in 2017, these sanctions have not only left civil society to face the Sudanese government alone but have also crippled the economy.

Several factors impede international support for Sudanese women’s participation in this movement. Volatile political realities and the challenging operating environment in Sudan limited diplomatic responses to calls for change, particularly those coming from women. The European Union issued a strong statement threatening to pull key funding in response to the TMC’s attacks against protesters. They have also issued statements condemning the attacks on civilians along with the governments of the United States, United Kingdom, and Norway. No government statements mentioned the specific targeting of WHRDs nor called for their inclusion in peace processes. Statements alone are insufficient; for example, expressing public support for an independent investigation into the paramilitary violence would be a powerful action.

Several factors impede international support for Sudanese women’s participation in this movement. Volatile political realities and the challenging operating environment in Sudan limited diplomatic responses to calls for change, particularly those coming from women. The European Union issued a strong statement threatening to pull key funding in response to the TMC’s attacks against protesters. They have also issued statements condemning the attacks on civilians along with the governments of the United States, United Kingdom, and Norway. No government statements mentioned the specific targeting of WHRDs nor called for their inclusion in peace processes. Statements alone are insufficient; for example, expressing public support for an independent investigation into the paramilitary violence would be a powerful action.

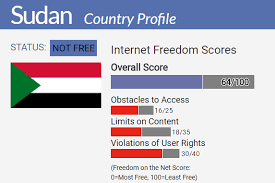

Simultaneously, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates pour money into the counter-revolution, fearful of what a successful democratic transition in the region may mean for them. Meanwhile, regional and international civil society stands in solidarity with Sudanese WHRDs. International media called attention to the plights and efforts of Sudanese WHRDs. Yet internet blackouts and the fragile security situation hamper their ability to intervene. In this transitional phase, the international community must keep the pressure on governing actors while pursuing creative ways to support WHRDs.

What is within the realm of the possible?

First and foremost, the international diplomatic community – including the US government – must ratchet up diplomatic engagement with Sudan. For example, efforts to expand civilian rule could be met with beginning discussions for removing Sudan from the list of state sponsors of terrorism. Governments must uphold their commitment to protecting WHRDs, even if support can only be expressed through public or private statements. They must also call out the violence aimed at WHRDs and insist upon their inclusion at every stage of the transition. Two seats out of 10 are not enough; moreover, that should not be the end of women’s participation in the transition. With a newly appointed special envoy to Sudan, the State Department is well-positioned to make headway. Ambassador Booth is charged with negotiating a peaceful political solution for Sudan’s future in conjunction with all relevant parties– and Sudanese WHRDs are key stakeholders in this process. The recently published White House Women, Peace, and Security Strategy also provides a framework to bolster women’s participation in fragile environments.

First and foremost, the international diplomatic community – including the US government – must ratchet up diplomatic engagement with Sudan. For example, efforts to expand civilian rule could be met with beginning discussions for removing Sudan from the list of state sponsors of terrorism. Governments must uphold their commitment to protecting WHRDs, even if support can only be expressed through public or private statements. They must also call out the violence aimed at WHRDs and insist upon their inclusion at every stage of the transition. Two seats out of 10 are not enough; moreover, that should not be the end of women’s participation in the transition. With a newly appointed special envoy to Sudan, the State Department is well-positioned to make headway. Ambassador Booth is charged with negotiating a peaceful political solution for Sudan’s future in conjunction with all relevant parties– and Sudanese WHRDs are key stakeholders in this process. The recently published White House Women, Peace, and Security Strategy also provides a framework to bolster women’s participation in fragile environments.- Second, donors should consider pumping additional funding into existing flexible, rapid response mechanisms, especially those designated for WHRDs. More funding should be dedicated to WHRDs specifically; funding for women’s organizations – despite their critical role – continues to be abysmal, with less than 1 percent of gender equality-focused aid reaching local women’s groups. Mechanisms such as Lifelineplay a key role in sustaining defenders under attack in challenging environments.

Third, international civil society must push for visibility for the situation in Sudan. They must keep Sudan on the policy agenda – as well as emphasize WHRDs as the essential factor in achieving a durable peace. Boosting the voices of Sudanese WHRDs through international media and holding the TMC accountable for its actions before and after the transition are imperative.

Third, international civil society must push for visibility for the situation in Sudan. They must keep Sudan on the policy agenda – as well as emphasize WHRDs as the essential factor in achieving a durable peace. Boosting the voices of Sudanese WHRDs through international media and holding the TMC accountable for its actions before and after the transition are imperative.- Finally, the US Congress should continue to be a champion of democracy and governance in the long term for Sudan. Democracy, rights, and governance programming remains under threat. As Sudan transitions, levels of US democracy support should be sustained – or preferably increased – with an emphasis on improving gender equality.

There are concrete, meaningful actions stakeholders can undertake to protect Sudanese women. These efforts cannot wait. Without WHRDs, the al-Bashir regime would likely have survived. And without guaranteeing their protection and ability to continue their work, peace and democracy in Sudan will be impossible. Now is the time for Sudan to head in the right direction – but only if WHRDs are able to fully participate. Ensuring women are in decision-making roles – and enshrining gender equality in a new constitution – are integral for Sudan’s stability.