Faced with the dispiriting state of global democracy,* worried observers fret over three basic questions: Why is this democratic recession happening? How bad is it? And where is it heading? Thomas Carothers asks.

Readers will come away from Sheri Berman’s Democracy and Dictatorship in Europe: From the Ancien Régime to the Present Day with useful insights on the vital question of why democracy sometimes succeeds but often does not. But Berman (a contributor to the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy) does not explicitly grapple with a further crucial question: As events push Western democracy into uncharted waters, how much can democracy’s past reveal about its future? Carothers writes for Foreign Affairs:

Broadly speaking, European and other Western democracies were built on the back of two centuries of remarkable economic growth, albeit with major shocks along the way. Now, the West is in for a protracted, possibly indefinite, period of slow growth or even stagnation. It’s not clear whether the liberal democratic consensus can withstand the inevitable public anger and alienation that will result. The toxic political fallout of the financial crisis does not bode well.

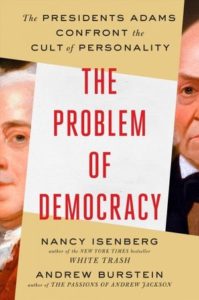

The Problem of Democracy, a new joint biography of John and John Quincy Adams, the second and sixth presidents, written by Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein, considers the role of personality in politics, NPR’s Scott Detrow reports. Subtitled The Presidents Adams Confront The Cult Of Personality, the book notes that throughout their careers they wrestled with the idea of democracy: what form governments should take; what sort of men should serve or even vote; and how much of a buffer should exist between governing and popular opinion.

The Problem of Democracy, a new joint biography of John and John Quincy Adams, the second and sixth presidents, written by Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein, considers the role of personality in politics, NPR’s Scott Detrow reports. Subtitled The Presidents Adams Confront The Cult Of Personality, the book notes that throughout their careers they wrestled with the idea of democracy: what form governments should take; what sort of men should serve or even vote; and how much of a buffer should exist between governing and popular opinion.

The problem for the illiberal populist governments in Poland and Hungary is that they are now no longer insurgents but the establishment, and so voters look elsewhere, as they did in Turkey recently as they tire of Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s populist EU-bashing demagogy that could fit in well with France’s Marine Le Pen or Italy’s Matteo Salvini, argues former UK Europe Minister Denis MacShane.

As with the many who marched in London against Brexit or the 6m who petitioned for Article 50 to be revoked, voters are not ready to follow populist, often xenophobe nationalist politicians to the point of breaking Europe apart. This does not mean European voters are falling in love with Brussels, but the line in recent years from UK academics and the commentariat, that the irresistible rise of the right cannot be successfully opposed, is wrong, he writes for the FT.

*As monitored by Democratic Decay & Renewal (DEM-DEC).