Marine Le Pen’s far-right political party is looking to deepen its ties to a nascent pan-European populist movement in the run-up to next year’s European Parliament elections, The Financial Times reports.

Marine Le Pen’s far-right political party is looking to deepen its ties to a nascent pan-European populist movement in the run-up to next year’s European Parliament elections, The Financial Times reports.

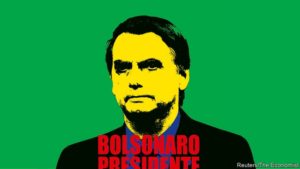

The populist upsurge is manifesting itself in an especially nasty form in its political home – Latin America.

The national elections next month give Brazil the chance to start afresh. Yet if, as seems all too possible, victory goes to Jair Bolsonaro, a right-wing populist, they risk making everything worse. Mr Bolsonaro, whose middle name is Messias, or “Messiah”, promises salvation; in fact, he is a menace to Brazil and to Latin America, The Economist notes:

Economist

Bolsonaro might not be able to convert his populism into Pinochet-style dictatorship even if he wanted to. But Brazil’s democracy is still young. Even a flirtation with authoritarianism is worrying. All Brazilian presidents need a coalition in congress to pass legislation. Mr Bolsonaro has few political friends. To govern, he could be driven to degrade politics still further, potentially paving the way for someone still worse.

Bad economics breeds bad politics. The global financial crisis, and the botched recovery thereafter, put wind in the sails of political extremism, notes Robert Skidelsky, Professor Emeritus of Political Economy at Warwick University. But it is very hard for liberals to accept that bad politics can produce good economics, and that good politics can produce bad economics, he writes for Project Syndicate:

And yet Hungary offers a clear example of the former. Under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, the country has become increasingly authoritarian. But the government’s economic program, “Orbánomics,” has a sound Keynesian footing. By the same token, good politics can certainly coexist with bad economics: Former British Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne’s austerity policies condemned the United Kingdom to years of stagnation.

And yet Hungary offers a clear example of the former. Under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, the country has become increasingly authoritarian. But the government’s economic program, “Orbánomics,” has a sound Keynesian footing. By the same token, good politics can certainly coexist with bad economics: Former British Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne’s austerity policies condemned the United Kingdom to years of stagnation.

A good economics in our own era would do three things: It would take precautions against 2008-level collapses; it would muster a robust counter-cyclical response to any collapse that does happen; and it would heed popular demands for economic fairness, Skidelsky adds:

Likewise, preserving today’s good politics also requires that we give urgent attention to four topics: the political and social limits of globalization; the financialization of the real economy; the role of fiscal and monetary policy; and the delinking of rewards from work in an era of accelerating automation.

Any account of populism today has to take into account what one might call the changing infrastructure of democracy, and the new media landscape in particular. It will also have to suggest ways in which particular demands within a democracy can be addressed without reducing them to the stuff of tribal identity and culture wars—which is, after all, the business model of populists, notes Princeton University’s Jan-Werner Muller, author of What is Populism? (Penguin, 2017).

Any account of populism today has to take into account what one might call the changing infrastructure of democracy, and the new media landscape in particular. It will also have to suggest ways in which particular demands within a democracy can be addressed without reducing them to the stuff of tribal identity and culture wars—which is, after all, the business model of populists, notes Princeton University’s Jan-Werner Muller, author of What is Populism? (Penguin, 2017).

William Galston ‘s Anti-Pluralism: The Populist Threat to Liberal Democracy puts four distinct concepts into play, he writes for Democracy: a Journal of Ideas:

William Galston ‘s Anti-Pluralism: The Populist Threat to Liberal Democracy puts four distinct concepts into play, he writes for Democracy: a Journal of Ideas:

- the republican principle, which he equates with popular sovereignty;

- democracy, which, following the seminal contributions by the political scientist Robert Dahl, he defines as majoritarianism limited by basic rights essential to popular will formation (most importantly, freedoms of speech, assembly, and the media);

- constitutionalism as an enduring framework for both enabling and constraining the exercise of public power;

- and, last but not least, liberalism as a set of limits on what the state can do to individuals.

It’s important to note that these liberal protections are different from the basic rights crucial for democracy: A religious minority can have its chances for self-expression curtailed, as with the headscarf bans that have been spreading across Europe. Such a measure is clearly illiberal; but it’s not the same as the attempts by, for instance, the current Polish and Hungarian governments to restrict freedoms of assembly—actions that are clearly anti-democratic.

Galston’s complex scheme is helpful in understanding not only what populism is but also what it is not, Muller adds.

How do populism and nationalism challenge democracy? Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences asks. Can they instead help to sustain it? This panel explores the causes of the global populist upsurge, from popular discontent to economic shocks. Nationalism and populism are powerful, compatible, and resonant ideologies. As a result, they can legitimate leaders and mobilize citizens – and pose dramatic challenges to liberal democracy [an issue addressed in the latest issue of the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy}.

How do populism and nationalism challenge democracy? Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences asks. Can they instead help to sustain it? This panel explores the causes of the global populist upsurge, from popular discontent to economic shocks. Nationalism and populism are powerful, compatible, and resonant ideologies. As a result, they can legitimate leaders and mobilize citizens – and pose dramatic challenges to liberal democracy [an issue addressed in the latest issue of the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy}.

Tuesday, October 23, 2018 5:30 pm Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University RSVP