There are many similarities between American consultant-turned-ideologue Steve Bannon and Hungarian liberal-turned-ultraconservative Viktor Orban. Both have a missionary mind-set; both are interested in ideas; both are obsessed with what they perceive as the spiritual crisis of the West; neither lacks in self-confidence and ambition, notes Ivan Krastev (left), the chairman of the Center for Liberal Strategies, and the author, most recently, of “After Europe.”

There are many similarities between American consultant-turned-ideologue Steve Bannon and Hungarian liberal-turned-ultraconservative Viktor Orban. Both have a missionary mind-set; both are interested in ideas; both are obsessed with what they perceive as the spiritual crisis of the West; neither lacks in self-confidence and ambition, notes Ivan Krastev (left), the chairman of the Center for Liberal Strategies, and the author, most recently, of “After Europe.”

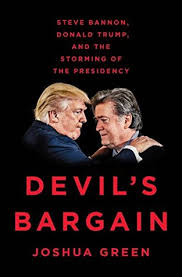

Right-wing Tea Party-style populism was a global phenomenon, Bannon told told a conference in Budapest, as Joshua Green writes in his book “Devil’s  Bargain.” But what really brings Mr. Bannon and Mr. Orban together is not just that they envision the European Union as an enemy to be destroyed, but also that they also believe that the populist revolt can and should be a cultural revolution, he writes for The New York Times.

Bargain.” But what really brings Mr. Bannon and Mr. Orban together is not just that they envision the European Union as an enemy to be destroyed, but also that they also believe that the populist revolt can and should be a cultural revolution, he writes for The New York Times.

A week after Mr. Bannon announced plans for The Movement, a cross-border Illiberal International, Mr. Orban declared that voters have given him a “mandate to build a new era” and that “an era is a special and characteristic cultural reality.” Mr. Bannon’s political mentor, the far-right publisher Andrew Breitbart, similarly insisted that “politics is downstream from culture.”

The rise of authoritarian chauvinism and xenophobia in Central and Eastern Europe has its roots not in political theory, but in political psychology, according to Krastev, a permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna, and Stephen Holmes, the Walter E. Meyer Professor of Law at New York University. It reflects a deep-seated disgust at the post-1989 “imitation imperative,” with all its demeaning and humiliating implications, they write for  the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy:

the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy:

The origins of the region’s current illiberalism are emotional and pre-ideological, rooted in rebellion at the humiliations that must necessarily accompany a project requiring acknowledgment of a foreign culture as superior to one’s own. Illiberalism in a strictly theoretical sense, then, is largely a cover story. It lends a patina of intellectual respectability to a desire, widely shared at a visceral level, to shake off the colonial dependency implicit in the very project of Westernization…

…..they add in an essay which draws on their forthcoming book The Light that Failed: How the West Won the Cold War and Lost the Peace (Penguin, 2019).

The region’s illiberal regimes are engaged in historical revisionism in order to legitimize their authoritarian turn, writes Arch Puddington, Distinguished Scholar for Democracy Studies at Freedom House.

Freedom House

In Hungary, a reinterpretation of Hungary’s 1956 revolt appears designed to bolster Orbán’s broader view of the nation’s history, which pits alien leftist and liberal forces against the defenders of Hungarian sovereignty and identity…..In Poland, where Jaroslaw Kaczyński’s right-wing Law and Justice party has carried out a similar attack on judicial independence and other democratic checks and balances, government officials have advocated the revisionist idea that Poland’s 1989 revolution, driven by the Solidarity labor movement, was betrayed by its leaders when they pursued the country’s eventual integration with Western Europe.

“Fifty years on, new threats to the values that inspired the Prague Spring demand a revived movement for democracy, with tactics and ideas suitable to the task,” he adds. “Among other things, such a movement must recognize that lies about the past are no less dangerous than lies about the present.”

While ideological affinity and mutual admiration are important, they’re not enough to explain this American-Hungarian axis. There are also purely tactical reasons. From Mr. Orban’s perspective, Mr. Bannon has a lot to offer, Krastev argues in The Times:

While ideological affinity and mutual admiration are important, they’re not enough to explain this American-Hungarian axis. There are also purely tactical reasons. From Mr. Orban’s perspective, Mr. Bannon has a lot to offer, Krastev argues in The Times:

- First, Mr. Bannon can help Mr. Orban convince Western European populists that there is nothing wrong with the prime minister of a small East European nation becoming the informal leader of their movement.

- Second, Mr. Bannon’s presence can shield the European far right from the suspicion that euroskeptics are simply Vladimir Putin’s puppets and an instrument in the Kremlin’s designs to destroy the European Union. Isn’t it better for the European far right to be associated with an American radical than with the Russian president?

Third, Mr. Bannon’s campaigning talent and his experience of waging war on the so-called mainstream media could be very useful. According to a recent Pew survey, mistrust of the mainstream media is the distinctive feature of Europe’s populist voter. No one knows as well as Mr. Bannon how to deepen this mistrust.

Third, Mr. Bannon’s campaigning talent and his experience of waging war on the so-called mainstream media could be very useful. According to a recent Pew survey, mistrust of the mainstream media is the distinctive feature of Europe’s populist voter. No one knows as well as Mr. Bannon how to deepen this mistrust.- Finally, Mr. Orban intends to make the 2019 European parliamentary elections a referendum on migration and Islam — two topics that animate many conservative voters. But that might not be so easy. In the past year, the flow of migrants into Europe has drastically declined, and most of the mainstream parties on the right — and even some on the left — have adopted a soft version of closed-borders politics sought by Central Europeans. So Mr. Orban needs Mr. Bannon to tell Europeans that only the far right understands immigration.