Russia’s invasion of Ukraine highlights the “existential battle between democracy and money,” according to Oliver Bullough, the author of a new paper from the International Forum for Democratic Studies at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

“It’s precisely because Ukraine is trying to dismantle kleptocracy” that Russia invaded, almost “as if Putin wanted to highlight the demonstration effect” of such efforts, he told a NED forum (above) to launch An Offshore Cold War: Forging a Democratic Alliance to Combat Transnational Kleptocracy.*

Prior to the invasion and to the unprecedented coordinated effort to impose financial sanctions on the Kremlin, Bullough writes; “Moscow would be much less bold in its demands on Ukraine and other neighbors if Germany were less willing to cut side deals to ensure its preferential access to natural gas, and if Britain were less prepared to let Kremlin-linked companies raise money in London’s capital markets.”

Prior to the invasion and to the unprecedented coordinated effort to impose financial sanctions on the Kremlin, Bullough writes; “Moscow would be much less bold in its demands on Ukraine and other neighbors if Germany were less willing to cut side deals to ensure its preferential access to natural gas, and if Britain were less prepared to let Kremlin-linked companies raise money in London’s capital markets.”

Democracies must forge a unified response to the critical challenge of kleptocracy, along the lines of the Cold War struggle against communism, he asserts, by highlighting the shared basic values of political and personal liberty, free markets, freedom of expression, and independent judicial systems.

Much like anticommunism encouraged Western countries to be better versions of themselves, anti-kleptocracy can be framed as a new mobilizing force to reboot democracies’ moral compasses and force them to stop engaging in enabling behavior, Bullough told the forum.

Countering kleptocracy will entail real costs for democracies, he concedes, but “in the long run, a society that is ruled in the interest of everyone, rather than in the interest of kleptocrats looting its resources, is far richer.”

The invasion of Ukraine has put Western democracies’ efforts to curb kleptocratic behavior “on steroids,” said NED President and CEO Damon Wilson, who moderated the event.

The invasion of Ukraine has put Western democracies’ efforts to curb kleptocratic behavior “on steroids,” said NED President and CEO Damon Wilson, who moderated the event.

“Look what it took to shake the West out of its complacency,” said German Marshall Fund President Heather Conley. Ukraine is showing us “what courage looks like” and highlighting “the cost of freedom.”

“Western democracies have imported the Kremlin’s kleptocratic behavior,” corrupting our own financial and political systems, she added. “Now is the time to quadruple down on support for civil society, investigative journalism, and transparency, for the people to hold governments accountable.”

With kleptocratic regimes the world over extending their influence and threatening democracy, the transatlantic community’s open societies need to wake up to the threat, Bullough writes in his report. Democracies may believe that their institutions are resilient enough to resist kleptocratic influence, but the evidence suggests otherwise.

To combat kleptocracy effectively, open societies must coordinate efforts and focus on shared fundamental values to develop a unified response and draw on the resilience and unity demonstrated in the fight against communism during the Cold War, he contends.

To combat kleptocracy effectively, open societies must coordinate efforts and focus on shared fundamental values to develop a unified response and draw on the resilience and unity demonstrated in the fight against communism during the Cold War, he contends.

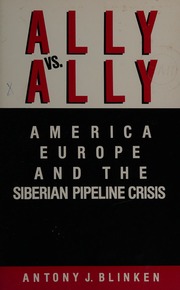

Others might be cautious about invoking or at least overly stressing the West’s Cold War anti-Communist unity. For example, the US was vehemently opposed to European support for a Russian gas pipeline – no, not Nord Stream. but the Soviet’s trans-Siberian pipeline. The transatlantic rift was the subject of a book, Ally Versus Ally: America, Europe, and the Siberian Pipeline Crisis, written by a certain Antony J. Blinken.

But certainly the democracies’ unprecedented “energetic unity” in responding to the invasion does suggest that there is scope for what NED’s Wilson called a new “generational movement” to enhance democratic resilience by expunging kleptocracy from the West’s political and financial architecture.

“Some of the decisions that we’ve seen coming out of what is a horrific Russian attack on Ukraine have the power of mobilizing collective action among democracies,” he said.

Ukrainians “never thought there would be war,” said Askold Krushelnycky, a British journalist of Ukrainian heritage and the author of the 2006 book, An Orange Revolution – A Personal Journey Through Ukrainian History.

Ukrainians “never thought there would be war,” said Askold Krushelnycky, a British journalist of Ukrainian heritage and the author of the 2006 book, An Orange Revolution – A Personal Journey Through Ukrainian History.

“When it did happen in 2014, they say it forced people to think about their identity – whether they were pro-Russia, or even if they had some doubts about the Ukrainian government. Overwhelmingly they stuck with the Ukrainian government,” he told the UK’s Daily Express.

“There’s a joke here that we should build Putin a statue because he’s done more to cement national unity than any Ukrainian president.”

Berlin’s Hertie School hosts two events featuring regional voices of activists and academics, now all exiled. (HT: former NED Reagan-Fascell fellow and Lipset lecturer Alina Mungiu-Pippidi).

*Read the full paper here.