Kazakhstan’s dictatorship appears to have all of the necessary institutions in place to facilitate a smooth transition after Nursultan Nazarbayev. The regime is set up to benefit from the presence of the Nur Otan party, the continued operation of the Kazakh parliament and a constitutionally mandated process for selecting a new president, notes Austin S. Matthews, a research associate at the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures at the University of Denver.

What does political science research tell us about what might come next for Kazakhstan’s ruling politicians? These three factors may help promote a stable transition, he writes for The Washington Post’s Monkey Cage:

1. Rules of succession restrain ambitious governing elites

After a dictator leaves office, members of the top leadership typically jockey for more power. This elite infighting can lead to violent repression or even a regime-ending coup. What keeps political ambitions in check during periods of transition? Having clear rules of succession in place that keep leadership changes orderly are typically beneficial for current and future dictators. Erica Frantz and Elizabeth A. Stein suggest that succession rules help dictators survive in office longer by putting procedures in place that lower the probability of a coup attempt. …

2. Legislatures win the cooperation of opposition elites

Most dictatorships also have legislatures — though their function and powers differ significantly from those of their democratic counterparts. It can be easy to dismiss legislatures within dictatorships as “window dressing,” something the government keeps around to make a dictatorship seem more like a representative democracy. However, even if they do not actually facilitate democratic values, these institutions are very important to the survival of dictatorships.

3. Political parties help keep the masses passive and supporters organized

YouTube

Political scientists also believe the presence of a ruling political party during leadership transitions can be beneficial for the regime. Parties serve as a mass organization that can help ensure the cooperation of the general public, either through surveillance or by buying loyalty with material goods….

“The experiences in neighboring Uzbekistan and nearby Turkmenistan, countries that have successfully transitioned leaders under similarly institutionalized dictatorships, suggest there’s reason to believe the Kazakhstan regime also will survive,” Matthews adds.

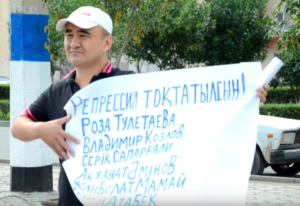

As the UN prepares to review Kazakhstan’s human rights record for the third time this year, the situation for human rights defenders ought to be under the spotlight, says Sarah McCloskey. Just a year and a half after this last review, environmental activist Max Bokayev (above) was first subjected to the beginning of an ongoing series of human rights violations. His case epitomises some of the significant risks that activists in Kazakhstan face, she writes for Open Democracy:

As the list of violations against rights defenders grows, so the space for civil society shrinks and activism freezes in Kazakhstan. The causes that they ordinarily advocate for are permitted to deteriorate and the authorities responsible are left unaccountable….In the meantime, the upcoming review at the UN level provides an opportunity to bring the civil society situation in Kazakhstan to the forefront of the international consciousness.

The Government of Kazakhstan is, however, reportedly concerned with its public image abroad, which gives civil society some leverage, says the NED-based World Movement for Democracy.

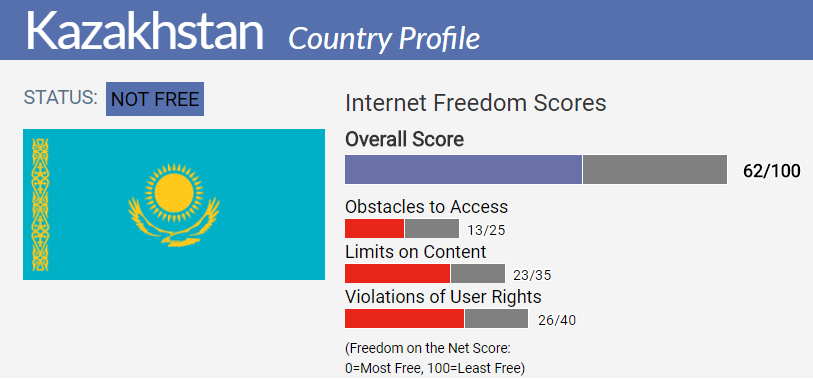

Democracy watchdog Freedom House deems Kazakhstan a “consolidated authoritarian regime” that has become less democratic and more repressive over the past decade.