Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban receives generally positive ratings from people in his own country, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted shortly after his reelection this spring. However, he gets mixed reviews for his impact on democracy in Hungary, and attitudes toward him are less positive among young people and residents of urban areas, including the country’s capital city, Budapest, Pew’s Laura Clancy writes:

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban receives generally positive ratings from people in his own country, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted shortly after his reelection this spring. However, he gets mixed reviews for his impact on democracy in Hungary, and attitudes toward him are less positive among young people and residents of urban areas, including the country’s capital city, Budapest, Pew’s Laura Clancy writes:

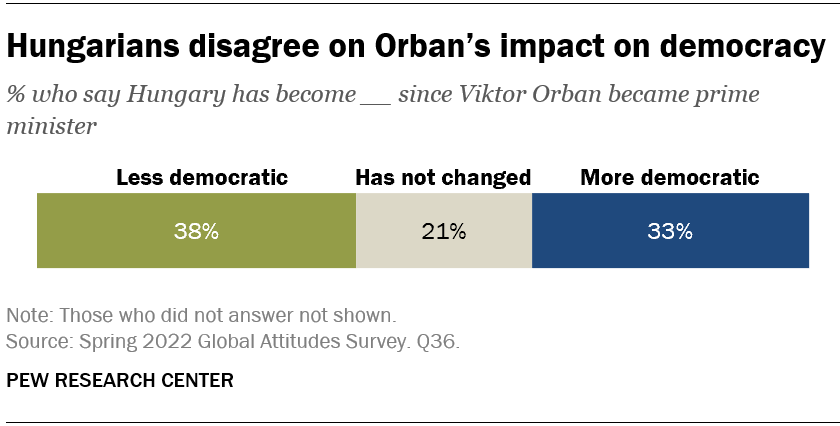

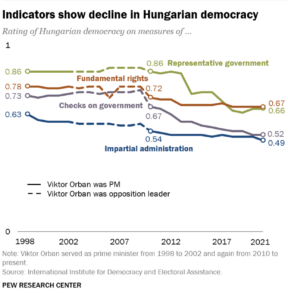

About four-in-ten Hungarian adults (38%) say their country has become less democratic since Orban became prime minister. A third say it has become more democratic, and about two-in-ten (21%) say it has not changed….. Indicators from the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance show a significant backslide in democracy in Hungary since 1998, when Orban took office for the first time as prime minister. The sharpest decline in these indicators – which measure representative government, fundamental rights, checks on government power and impartial administration – appear after 2010, when Orban began his second stint as prime minister.

About four-in-ten Hungarian adults (38%) say their country has become less democratic since Orban became prime minister. A third say it has become more democratic, and about two-in-ten (21%) say it has not changed….. Indicators from the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance show a significant backslide in democracy in Hungary since 1998, when Orban took office for the first time as prime minister. The sharpest decline in these indicators – which measure representative government, fundamental rights, checks on government power and impartial administration – appear after 2010, when Orban began his second stint as prime minister.

With funds dwindling, Orbán’s system of supporting oligarchs so that they in turn support him may crack, notes Kim Lane Scheppele, the Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Sociology and International Affairs at Princeton University. If that were to happen, Hungary might spin into the sort of democratic death spiral that we have seen in Russia, Turkey, and Venezuela, where slipping political support has led to increasing political repression, which in turn has pushed investors to flee and bring down the economy.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

Being in the EU might moderate the effects of economic implosion in Hungary—though at a tremendous cost to the EU—but even a less dramatic crash would be a painful ending. It may be the only one, however, that Orbán cannot prevent, she writes for the Journal of Democracy.

Still, experts say Orban’s near-total control of his country makes him a pioneer of a new approach to anti-democratic rule, The Washington Post adds.

“I’ve never seen an autocrat consolidate authoritarian rule without spilling a drop of blood or locking someone up,” said Steven Levitsky, a Harvard political scientist and co-author of the book “How Democracies Die.” He and other scholars said Orban qualifies as an authoritarian because of his use of government to control societal institutions.

Peter Kreko

Peter Kreko (right), a Budapest-based analyst for the Center for European Policy Analysis, said Orban’s anti-democratic tendencies won’t be a big issue in his quest to forge an alliance with U.S. conservatives.

His closeness to Russia and China will be much thornier, said Kreko, a former Reagan-Fascell fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).