American Purpose

The “democracy” under attack today is a shorthand for liberal democracy, and what is really under greatest threat is the liberal component of this pair, says a leading analyst.

Liberalism is connected to democracy, but is not the same thing, notes Francis Fukuyama, the Olivier Nomellini Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI), the director of the Ford Dorsey Master’s in International Policy, and the Mosbacher Director of FSI’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law.

It is possible to have regimes that are liberal but not democratic: Germany in the 19th century and Singapore and Hong Kong in the late 20th century come to mind. It is also possible to have democracies that are not liberal, like the ones Viktor Orbán and Narendra Modi are trying to create that privilege some groups over others, he observes.

Liberalism is allied to democracy through its protection of individual autonomy, which ultimately implies a right to political choice and to the franchise. But it is not the same as democracy, he writes in an introductory essay for American Purpose, a magazine, media project, and intellectual community aiming to defend and promote liberal democracy.

Former NED board member Francis Fukuyama backs the initiative

The period from 1950 to the 1970s was the heyday of liberal democracy in the developed world. Liberal rule of law abetted democracy by protecting ordinary people from abuse, Fukuyama adds:

Liberal rule of law laid the basis for the strong post-World War II economic growth that then enabled democratically elected legislatures to create redistributive welfare states. Inequality was tolerable in this period because most people could see their material conditions improving. In short, this period saw a largely happy coexistence of liberalism and democracy throughout the developed world.

Vladimir Putin told the Financial Times that liberalism has become an “obsolete” doctrine. While it may be under attack from many quarters today, it is in fact more necessary than ever, Fukuyama insists. RTWT

In his 2007 Munich speech, Putin characterized unipolarity, and the West’s supremacy in global politics, as inherently undemocratic, notes MEMRI analyst Anna Mahjar-Barducci. “What is a unipolar world? However one might embellish this term, at the end of the day it refers to one type of situation, namely one center of authority, one center of force, one center of decision-making,” he said. “And this certainly has nothing in common with democracy. Because, as you know, democracy is the power of the majority in light of the interests and opinions of the minority.”

Creating an international “space” for liberal democracy, preserving rights and protections within and between countries, and balancing conflicting values such as liberty and equality, openness and social solidarity, and sovereignty and interdependence—these are the guiding aims that have propelled liberal internationalism through the upheavals of the past two centuries, claims G. John Ikenberry, the Albert G. Milbank Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton University in the Department of Politics and the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. In a twenty-first century marked by rising economic and security interdependence, liberal internationalism—reformed and reimagined—remains the most viable project to protect liberal democracy, he argues in A World Safe for Democracy: Liberal Internationalism and the Crises of Global Order.

Creating an international “space” for liberal democracy, preserving rights and protections within and between countries, and balancing conflicting values such as liberty and equality, openness and social solidarity, and sovereignty and interdependence—these are the guiding aims that have propelled liberal internationalism through the upheavals of the past two centuries, claims G. John Ikenberry, the Albert G. Milbank Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton University in the Department of Politics and the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. In a twenty-first century marked by rising economic and security interdependence, liberal internationalism—reformed and reimagined—remains the most viable project to protect liberal democracy, he argues in A World Safe for Democracy: Liberal Internationalism and the Crises of Global Order.

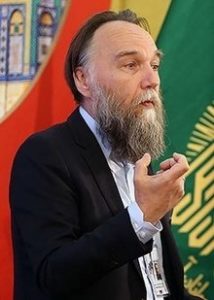

According to Russian anti-liberal philosopher Alexander Dugin, the system that should replace unipolarity is multipolarity, which can be better defined by describing what it opposes, Mahjar-Barducci adds: “Multipolarity is against unipolarity… Multipolarity is against hegemony on three levels – first of all strategic, i.e., against the American military domination of the world with American military bases everywhere in the world… Multipolarity is against ideological hegemony as globalization, liberalism, and human rights…”

Wikipedia: Alexsander Dugin

Dugin (right) describes the West’s concept of human rights as inherently “racist”, since it affirms the liberal concept of the individual as “the only way to understand human nature.”

However, after defining what multipolarity is by what it stands against, Dugin explains that a pole is not only strategic or political: “It is linked to a civilization as a culture or special type of society with special values. At the same time, it is not only a culture, but also a strategic space. Thus, in the concept of pole, we have both meanings: power and idea. The ideological and cultural levels and military force are inscribed into the pole in space, in political geography, and in cultural geography at the same time.”

The “democracy” under attack today is a shorthand for liberal democracy, and what is really under greatest threat is the liberal component of this pair, @StanfordCDDRL‘s @FukuyamaFrancis writes for @americanpurpose https://t.co/fEwGRuXc1S

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 5, 2020