A new anti-government protest in Moldova’s capital Tuesday stirred fears of more unrest after thousands of demonstrators took to the streets to demand that the country’s new pro-Western government fully subsidize citizens’ winter energy bills and to “not involve the country in war,” The Post reports. The protest in Chisinau was organized by a group calling itself Movement for the People and supported by members of Moldova’s Russia-friendly Shor Party, which holds six seats in the country’s 101-seat legislature.

The protest also comes a day after Moldova’s Intelligence and Security Service, SIS, said it had expelled two foreign nationals who were caught carrying out “subversive actions” to destabilize Moldova, it adds. The SIS said that the pair were actively monitoring and documenting social and political processes in Moldova, including protests it said were “organized in the capital by certain political forces.”

U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Karen Donfried told RFE/RL that the United States is “deeply concerned” about reports about a plot to undermine the government and strongly supports Sandu.

Freedom House

Moldova looks like “the next Ukraine.” So said Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov the other day. Obviously, that should worry us. When Lavrov muses that Moldova looks like the next Ukraine, he’s implying that it’s the next country in Russia’s sphere of influence trying to defect to the evil West, requiring Russia to infiltrate or occupy or otherwise attack it — in pre-emptive “self-defense,” it goes without saying. Here’s what Lavrov meant, the Economist’s Andreas Kluth writes for Bloomberg:

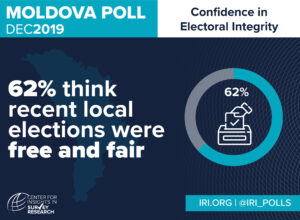

A recent poll in Moldova by the International Republican Institute’s (IRI) Center for Insights in Survey Research (CISR) showed strong support for European Union (EU) membership, concern over the state of the economy, and trust in President Maia Sandu’s leadership.

A recent poll in Moldova by the International Republican Institute’s (IRI) Center for Insights in Survey Research (CISR) showed strong support for European Union (EU) membership, concern over the state of the economy, and trust in President Maia Sandu’s leadership.

“This data clearly demonstrates that Moldovans desire to be part of the European Union,” said Stephen Nix, IRI’s Senior Director for Eurasia. “They understand that Western institutions are essential to a future that will provide peace and prosperity.”

The Moldovan leadership, under President Sandu (above), has now moved to extricate the country from the Russian-dominated process of negotiations on Transnistria, notes Jamestown analyst Vladimir Socor. For the first time in 30 years, leadership has emerged in Chisinau with the motivation and skill to promote a Transnistria solution in line with Moldova’s Europeanization process, as distinct from and opposed to Russia’s interests in Moldova and the wider region.

Moldova is important inherently to the millions of people who live there, of course, but also because of its geographic position between Ukraine and NATO, and because it is on the front lines of the struggle between authoritarianism and freedom, argue analysts Eric Edelman, David J. Kramer, and Benjamin Parker.* If Moldova fails, it will be a victory for Putin at a time when he desperately needs one and a defeat for the liberal-democratic world when it most needs to keep up its confidence and resolve, they write for The Bulwark:

Moldova is important inherently to the millions of people who live there, of course, but also because of its geographic position between Ukraine and NATO, and because it is on the front lines of the struggle between authoritarianism and freedom, argue analysts Eric Edelman, David J. Kramer, and Benjamin Parker.* If Moldova fails, it will be a victory for Putin at a time when he desperately needs one and a defeat for the liberal-democratic world when it most needs to keep up its confidence and resolve, they write for The Bulwark:

- To prevent such a scenario, the West needs to ramp up its support for Moldova and, much like it did in the lead-up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, disclose intelligence it may have regarding any designs the Kremlin may have on Chisinau.

- The EU should accelerate its negotiations on membership and bolster Sandu and the new government.

- NATO should consider military support that would make Moldova like a porcupine, difficult for Russia to swallow.

- Much like President Biden’s important visit to Kyiv on Monday, a stop in Chisinau by the secretary of state or secretary of defense would signal strong American backing for Moldova.

While keeping a close eye on Russia’s subversive plans in Moldova that have a lower probability, the Moldovan authorities must properly monitor and manage internal socio-economic stability, adds political analyst Denis Cenusa. That is the weakest point exploited by pro-Russian forces, and one that Moscow managed to inflame in 2022. If Russia fails with short-term tactics, it could succeed with longer-term strategies involving democratic means taking into account Moldova’s local elections in 2023, the presidential ones in 2024 and the legislative ones in 2025, he writes for The Riddle.

While keeping a close eye on Russia’s subversive plans in Moldova that have a lower probability, the Moldovan authorities must properly monitor and manage internal socio-economic stability, adds political analyst Denis Cenusa. That is the weakest point exploited by pro-Russian forces, and one that Moscow managed to inflame in 2022. If Russia fails with short-term tactics, it could succeed with longer-term strategies involving democratic means taking into account Moldova’s local elections in 2023, the presidential ones in 2024 and the legislative ones in 2025, he writes for The Riddle.

*Eric S. Edelman is counselor at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments and a non-resident senior fellow at the Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia. He is also the co-host of The Bulwark’s Shield of the Republic podcast. He was U.S. ambassador to Finland from 1998 to 2001 and under secretary of defense for policy from 2005 to 2009. David J. Kramer is executive director of the George W. Bush Institute and served as assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights, and labor in the George W. Bush administration. Benjamin Parker is a senior editor at The Bulwark.

Both Kyiv and Chisinau, in the Kremlin’s narrative, also want to join NATO and align with the US-led — and therefore basically Satanic — “West” against Russia. In Moldova’s case, that’s simply false — neutrality is written into its constitution.

Both Kyiv and Chisinau, in the Kremlin’s narrative, also want to join NATO and align with the US-led — and therefore basically Satanic — “West” against Russia. In Moldova’s case, that’s simply false — neutrality is written into its constitution.