Credit: EIU

In the year before the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, campuses in China buzzed with debate about how to make the country more liberal. To some intellectuals the West offered a model, The Economist writes:

In the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev had shown how a start could be made. Amid this ferment, in August 1988, a bespectacled political scientist arrived in America for half a year of study, initially at the University of Iowa. He found much to criticize but also plenty to admire in America: its universities, its innovation and the smooth transfer of power from one president to another. Capitalism, wrote the 32-year-old party member, “cannot be underestimated”.

That academic, Wang Huning, is now one of seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee of a party locked in an escalating ideological war with America, it adds. As its chief of ideology and propaganda, he is in charge of crafting a very different message: that China practices true democracy, that America’s is a sham and that American power is fading.

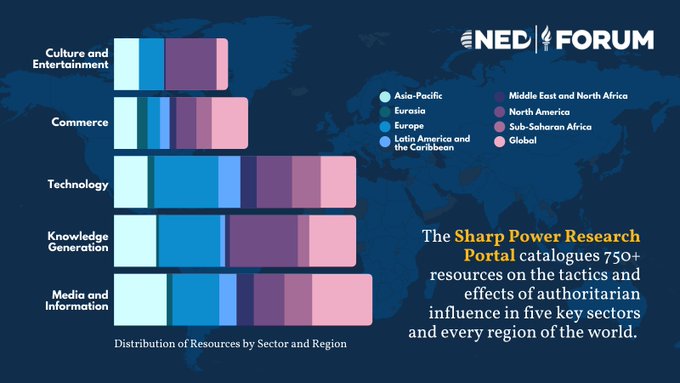

Wang Huning leads #CCP‘s ‘escalating ideological war* with America,’ @TheEconomist reports. *More of @ThinkDemocracy‘s #sharppower https://t.co/lGr0z2wOqP

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) February 11, 2022

How much of a challenge does China’s political model pose globally? That’s the principal question posed by The Economist Intelligence Unit’s latest annual Democracy Index.

Contrary to realist John Mearsheimer’s predictions, the fundamentals of demographics, geography, and the structure of the international system do not mean that China is destined to be the new global hegemon, Columbia University’s Andrew J. Nathan writes for Foreign Affairs.

Contrary to realist John Mearsheimer’s predictions, the fundamentals of demographics, geography, and the structure of the international system do not mean that China is destined to be the new global hegemon, Columbia University’s Andrew J. Nathan writes for Foreign Affairs.

In each area, China suffers from major weaknesses. It will not become, as he says it wants to, “the most powerful state in its backyard and, eventually, in the world.” Rather, it will remain one among several major powers both regionally and globally, presenting threats to important, but not existential, U.S. interests, notes Nathan, a former National Endowment for Democracy (NED) board member.

One might also add political and intellectual frailty to the list, judging by a Chinese official’s insistence to Jane Perlez in this weekend’s Financial Times that the National Endowment for Democracy orchestrated Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests:

As I was leaving China in the autumn of 2019, a friendly government official invited me to lunch. I looked forward to a warm farewell. Instead, I received a lecture on the perfidies of the US. The protests were under way in Hong Kong. My lunch partner told me Washington was to blame and, in particular, Allen Weinstein. Fortunately, I knew of Weinstein. “He’s dead,” I replied. He had died four years earlier. “It doesn’t matter. He was head of the National Endowment for Democracy” [Of course, he never was].

The inference was that the endowment was behind the demonstrations, Perlez adds. I did a little research and found the endowment had spent just under $640,000 in Hong Kong that year, a modest figure for an organization its size.

Even if we accept as broadly true the idea that there’s an ideological dimension to US-China competition, we’re not sure what exactly the competing ideologies are supposed to be, analyst Kaiser Kuo observes on the Sinica Podcast with Jason Wu, an assistant professor of political science at Indiana University in Bloomington. What is the positive content of Chinese ideology? How do familiar typologies of ideology — left or liberal, or progressive, right, or conservative, or reactionary — map onto China, if indeed they do at all? Is authoritarianism really an ideology?

Even if we accept as broadly true the idea that there’s an ideological dimension to US-China competition, we’re not sure what exactly the competing ideologies are supposed to be, analyst Kaiser Kuo observes on the Sinica Podcast with Jason Wu, an assistant professor of political science at Indiana University in Bloomington. What is the positive content of Chinese ideology? How do familiar typologies of ideology — left or liberal, or progressive, right, or conservative, or reactionary — map onto China, if indeed they do at all? Is authoritarianism really an ideology?

China is “not making a counter universalist argument” or engaging in ideological competition as in the Cold War, “exporting socialism versus exporting capitalism, democracy,” Wu insists.

The West should welcome a Cold War with China because it would mean averting a direct military confrontation and, even better, a Cold War is a winnable war, argues one observer.

If the competition with China is truly about the future of the 21st century—whether democracy as a creed and the American experiment as a civilization can survive in the face of its greatest challenge yet—the U.S. should be ecstatic at the prospects of a cold war, Gabriel Scheinmann, executive director of the Alexander Hamilton Society, writes for The Wall Street Journal:

Today, the American geopolitical position is strong even if Chinese gains have eroded the overall U.S. military advantage. The U.S. and its allies represent 50% of global GDP. Washington is allied with or has increasingly friendly relations with nearly every country in Asia. The strength of American soft power underscores the appeal of the U.S. democratic system and the American way of life. The Chinese government, on the other hand, fears its own people.

CREDIT: DEUTSCHE WELLE SCREEN GRAB

But a new cold war between authoritarian and democratic regimes is not inevitable, says CSIS expert Benjamin Jensen. Social media and the democratization of expertise create a chaotic marketplace of ideas that makes it difficult to prioritize strategic interests.

Worst still, polarization limits genuine bipartisan discussion. So Congress should form a bipartisan strategy commission and start a dialogue about American strategy for the 21st century, he writes for The Hill:

First, what is the international system and what role should the United States play, or any country for that matter, in shaping its future trajectory?… The United States cannot assume the international system we inherited, and deploy military forces globally to protect, is necessarily the optimal solution for peace and prosperity in the 21st century. No idea should be so sacred that it should resist hypothesis testing and alternative analysis.

Second, what threat is the priority? Is it adversary driven (i.e., China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, extremists), ideological (i.e., authoritarianism vs. democracy), or human-centric and linked to climate change, migration, economic inequality and/or public health? Strategy requires prioritization and assessing the inherent tradeoffs involved with pursuing competing interests. To use an old adage, “If everything is a priority, nothing is a priority”…..

Third, given a set of assumptions about the international system and a clear-eyed ranking of national security priorities, what is the optimal domain for competition? Even if one takes a human-centric approach and prioritizes climate change, migration (whether from a political right or left perspective) and inequality as the focal points for strategy, there still will be competition between nation-states. The art of statecraft is to find points of cooperation and coercion that shape the long-term competition in a manner that avoids inadvertent escalation, major war and self-defeating policies that drain national resources and sharpen domestic political divides.

Third, given a set of assumptions about the international system and a clear-eyed ranking of national security priorities, what is the optimal domain for competition? Even if one takes a human-centric approach and prioritizes climate change, migration (whether from a political right or left perspective) and inequality as the focal points for strategy, there still will be competition between nation-states. The art of statecraft is to find points of cooperation and coercion that shape the long-term competition in a manner that avoids inadvertent escalation, major war and self-defeating policies that drain national resources and sharpen domestic political divides.

A new strategy commission should embrace divergent thinking because we cannot, to quote Albert Einstein, “solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them,” Jensen adds.

Now, after decades of believing that China might someday fully join the multilateral economic system created after World War II, most U.S. officials no longer imagine that China can be more like us, The Washington Post’s Josh Rogin observes. Instead, the goal is to defend an international system that is under attack, protect the interests of the United States and its allies, and fight for the values that underpin our fundamental humanity against authoritarianism.

And within the Biden administration, it’s the “competitors” – including Secretary of State Antony Blinken; national security adviser Jake Sullivan; the National Security Council’s Indo-Pacific coordinator, Kurt Campbell; the NSC’s senior director for China and Taiwan, Laura Rosenberger; and other key officials – who are trying to cement a long-term strategy toward China, he adds.

But fostering an Indo-Pacific region with Western ideals cannot come at the expense of America’s traditional alliances, first and foremost with Europe, cautions Dr. Margarita Konaev, of the Center for a New American Security.

But fostering an Indo-Pacific region with Western ideals cannot come at the expense of America’s traditional alliances, first and foremost with Europe, cautions Dr. Margarita Konaev, of the Center for a New American Security.

“It makes sense for the U.S. to shift its primary focus to Asia to build alliances based on ideals of free and open economies and societies with democratic systems and respect for human and civil rights,” she tells Christian Science Monitor, “but if we don’t stand up for those principles where they are most threatened right now, what’s the point of mounting this competition with China?”

Mearsheimer is right that China presents a formidable challenge to the United States, adds G. John Ikenberry, Albert G. Milbank Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton:

The two countries are hegemonic rivals with antagonistic visions of world order. One wants to make the world safe for democracy; the other wants to make the world safe for autocracy. The United States believes—as it has for more than two centuries—that it is safer in a world where liberal democracies hold sway. China increasingly contests such a world, and therein lies the grand strategic rub.

But in the face of this challenge, the United States would do well to work with its allies to strengthen liberal democracy and the global system that makes it safe—and to do so while looking for opportunities to work with its chief rival, he suggests. RTWT