By pumping so much money through the hands of Ukrainian officials and businessmen — often the same people — the surge in military spending has held back efforts to defeat the corruption and self-dealing that many see as Ukraine’s most dangerous enemy…. Military spending, however, has opened up new vistas for opaque insider deals, sheltered from scrutiny by a cone of secrecy that covers the details of military spending, The New York Times reports:

YouTube

Daria Kaleniuk (right), director of the Anticorruption Action Center, a nongovernmental group in Kiev, said that transparency and accountability are national security issues that must be addressed if Ukraine is not only to create a functioning European-style democracy, but also to hold its own on the battlefield in the east.

“Corruption in the energy sector has been reduced, so some of the main avenues for corruption have moved to defense,” said Olena Tregub, the secretary general of the Independent Defense Anti-Corruption Committee, a research group funded by Western donors.

Ukraine’s pro-democracy and civil society activists fear that corruption is undermining the country’s democratic prospects.

Serhiy Leshchenko

“We are sliding back,” the Ukrainian journalist turned parliamentarian Serhiy Leshchenko [left, a former Reagan-Fascell fellow, at the National Endowment for Democracy] warned a year ago about the arc of political reform in his country.

In the last three decades, Ukraine has experienced three dramatic changes that have often been referred to as revolutions, notes Ruslan Minich, an analyst at Internews Ukraine and at UkraineWorld, an information and networking initiative. But were they genuinely revolutionary? he writes for The Atlantic Council:

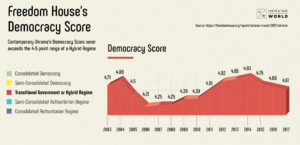

“While the first ‘revolution’ in 1990 precipitated a decline in late Soviet totalitarianism, it was not enough to push Ukraine onto the liberal reforms track,” said Yuriy Matsiyevsky, head of the Center for Political Research at Ostroh Academy National University. “By the end of the first term of Leonid Kuchma’s presidency in 1999, Ukraine had descended into a hybrid regime that combined competitive elections with corruption, cronyism, and nepotism. This still persists today.”….

“While the first ‘revolution’ in 1990 precipitated a decline in late Soviet totalitarianism, it was not enough to push Ukraine onto the liberal reforms track,” said Yuriy Matsiyevsky, head of the Center for Political Research at Ostroh Academy National University. “By the end of the first term of Leonid Kuchma’s presidency in 1999, Ukraine had descended into a hybrid regime that combined competitive elections with corruption, cronyism, and nepotism. This still persists today.”….

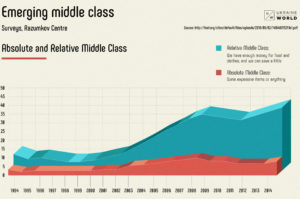

The 2004 Orange Revolution was a reaction to this post-communist kleptocratic and semi-criminal government. People took to the streets to protest against rigged presidential elections. They were hoping that opposition leaders would be able to change the regime. The driving force was the middle class, which had begun to emerge in the 2000s and demand political rights. “Young educated people whose basic needs have been satisfied and who represent values of self-expression are prone to protest,” said Yaroslav Hrytsak, a Ukrainian historian and professor at the Ukrainian Catholic University.

“Ukrainians must do these reforms for themselves”, says Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland (above).

“Ukrainians must do these reforms for themselves”, says Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland (above).

Ukrainians feel frustrated enduring the turbulence of this period of transformation, Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman concedes. There is fatigue, and there are many disappointments, which, as we have seen in many other countries, can be exploited by populists, he writes for The Wall Street Journal.

Ukraine’s President Petro Poroshenko on Saturday urged lawmakers to find a compromise on a draft law paving the way for a new anti-corruption court, AFP reports. The bill has come under fire from the local media and anti-corruption civil society groups, which have accused authorities in Kiev of seeking to trick their western partners. .

Ukraine is still an oligarch-infested kleptocracy that works a lot more like Russia than an EU country, notes one observer.

In the fall of 2017 Brussels started using the term “kleptocracy” to describe its partners in Kyiv, says analyst Mykhailo Minakov. In November, EU commissioners suspended the program of financial aid to Ukraine because of unfulfilled promises. Kyiv has slowed liberal reforms and tries to destroy anticorruption institutions and persecute opposition to the Poroshenko regime, he writes for the Wilson Center.

Since last year, civil society groups, journalists, anticorruption activists, and others have witnessed an ominous change in the environment for freedom of association in Ukraine. Freedom House’s recently released Freedom in the World report on the country underscored the government’s increased pressure on civil society organizations, in part through new legislation that especially affects groups focused on fighting corruption, notes Gina S. Lentine, the group’s Program Officer for Europe and Eurasia:

Since last year, civil society groups, journalists, anticorruption activists, and others have witnessed an ominous change in the environment for freedom of association in Ukraine. Freedom House’s recently released Freedom in the World report on the country underscored the government’s increased pressure on civil society organizations, in part through new legislation that especially affects groups focused on fighting corruption, notes Gina S. Lentine, the group’s Program Officer for Europe and Eurasia:

One of Ukraine’s leading civic activists, Vitaliy Shabunin (right) of the Anti-Corruption Action Center (ANTAC), is facing trial on criminal charges and could receive up to five years in prison. He was indicted on January 22 for supposedly inflicting bodily harm on a journalist. The charges are at best exaggerated and at worst politically motivated: Last summer, Shabunin threw a punch at Vsevolod Filimonenko, who some believe was sent by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) to harass ANTAC staff in retaliation for their outspoken criticism of President Petro Poroshenko’s failure to address endemic corruption in Ukraine.

One of Ukraine’s leading civic activists, Vitaliy Shabunin (right) of the Anti-Corruption Action Center (ANTAC), is facing trial on criminal charges and could receive up to five years in prison. He was indicted on January 22 for supposedly inflicting bodily harm on a journalist. The charges are at best exaggerated and at worst politically motivated: Last summer, Shabunin threw a punch at Vsevolod Filimonenko, who some believe was sent by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) to harass ANTAC staff in retaliation for their outspoken criticism of President Petro Poroshenko’s failure to address endemic corruption in Ukraine.

Even purported anti-corruption reformers like Mikhail Saakashvili have been compromised.

Saakashvili’s first term in office was, arguably, an unqualified success, notes Adrian Karatnycky, a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council and co-director of its Ukraine in Europe program: He removed an entrenched corrupt elite, implemented free-market reforms, drastically reduced red tape, and prompted impressive economic growth. But by his second term, Transparency International and other international monitoring groups claimed he was tolerating the rise of a new kleptocracy by empowering businessmen closely linked to his political party, he writes for POLITICO.

Saakashvili’s first term in office was, arguably, an unqualified success, notes Adrian Karatnycky, a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council and co-director of its Ukraine in Europe program: He removed an entrenched corrupt elite, implemented free-market reforms, drastically reduced red tape, and prompted impressive economic growth. But by his second term, Transparency International and other international monitoring groups claimed he was tolerating the rise of a new kleptocracy by empowering businessmen closely linked to his political party, he writes for POLITICO.

The suppressed traumas of distant and recent history continue to shape Ukrainian society negatively and are as big an obstacle to progress as more commonly discussed problems like corruption and the ongoing hybrid conflict with Russia, analyst Pete Shmigel argues at Ukraine Democracy Initiative.