At a bucolic border post, Western-trained Hungarian counterintelligence agents recently got word that a known operative of Russia’s foreign spy service was driving into Hungary, and asked headquarters for permission to pursue. Permission denied, came the firm order from Budapest, Drew Hinshaw and Marcus Walker write for The Wall Street Journal.

At a bucolic border post, Western-trained Hungarian counterintelligence agents recently got word that a known operative of Russia’s foreign spy service was driving into Hungary, and asked headquarters for permission to pursue. Permission denied, came the firm order from Budapest, Drew Hinshaw and Marcus Walker write for The Wall Street Journal.

This kind of incident is a regular occurrence at Hungary’s frontiers according to two former intelligence agents, and fits a pattern. Russian involvement in Hungary is growing, they observe in a must-read Saturday Essay:

Russian spies roam freely, using Budapest as a base to advance their aims in Europe, according to U.S. and Hungarian officials. Russian energy companies sign secretive deals that critics say aim to enrich and co-opt Hungarian oligarchs. Officials from the U.S. and European Union complain, but feel shut out by a government they view as more like Vladimir Putin’s than their own.

Russian spies roam freely, using Budapest as a base to advance their aims in Europe, according to U.S. and Hungarian officials. Russian energy companies sign secretive deals that critics say aim to enrich and co-opt Hungarian oligarchs. Officials from the U.S. and European Union complain, but feel shut out by a government they view as more like Vladimir Putin’s than their own.

Welcome to Europe’s new disorder. The U.S. and EU-led alliance in Europe that grew stronger after the Cold War is now splintering. Russia is seizing chances to encourage this fragmentation and regain influence. This time, Moscow’s intellectual currency isn’t Marxism, but an authoritarian style of leadership that sneers at the pieties of liberal democracy.

“Orban genuinely believes the West is on the decline, and the best days of the EU and NATO are numbered,” says David Koranyi, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington and a former Hungarian national-security official. “He’s pragmatic enough to keep Hungary in the EU and NATO for now, because the money coming in and the security umbrella still have their value. But he sees the 21st century as the rise of a competing governance model, that of the East.”

The Fidesz government has also launched an assault on civil society, most conspicuously on philanthropist George Soros’s Open Society foundations.

The Fidesz government has also launched an assault on civil society, most conspicuously on philanthropist George Soros’s Open Society foundations.

The decision by Soros’ foundation to uproot its Budapest office and move to Berlin — an echo of its 2016 expulsion from Russia by Putin — was a wrenching one, said spokesman Csaba Csontos. But senior Open Society officials felt they could not protect the local staff from harassment and intimidation, including surveillance, monitored communications and outlandish smear stories carried by outlets loyal to the government, The LA Times adds:

For more than 20 years, Soros’ vast wealth and political engagement, together with latent but virulent anti-Semitism in Europe and elsewhere, have made him an ideal target for right-wing forces, political analysts say. More recently, the growth of social media and the success of nationalist movements in Europe turbocharged his role as a scapegoat for the world’s ills.

Soros “fulfills the criteria the conspiracy theorists search for,” said Gustav Gressel, a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. “There is a growing skepticism against elites, free capitalism, free trade and freedom of movement. … The new right uses that.”

Soros “fulfills the criteria the conspiracy theorists search for,” said Gustav Gressel, a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. “There is a growing skepticism against elites, free capitalism, free trade and freedom of movement. … The new right uses that.”

“The world now may be more like the Eastern Europe into which he was born than the complacent world of Western freedoms,” said Mark Malloch Brown, a former deputy United Nations secretary-general who sits on the board of Soros’ foundation. “In a strange way, the setbacks he’s facing remind him of the lessons he learned as a youngster.”

Laboratory of Illiberalism

While an idiosyncratic sequence of particular events led to the ascendance of illiberal rule in Hungary, the causal factors involved are virtually omnipresent and could therefore lead to similar outcomes elsewhere, according to Péter Krekó, director of the Budapest-based Political Capital Institute, and Zsolt Enyedi, professor of political science at the Central European University in Budapest.

While an idiosyncratic sequence of particular events led to the ascendance of illiberal rule in Hungary, the causal factors involved are virtually omnipresent and could therefore lead to similar outcomes elsewhere, according to Péter Krekó, director of the Budapest-based Political Capital Institute, and Zsolt Enyedi, professor of political science at the Central European University in Budapest.

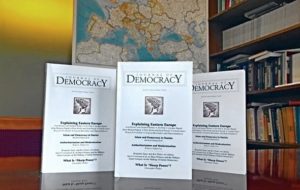

Hungary has become a successful laboratory of illiberal governance. Fidesz has remodeled the country’s institutions to suit ruling-party purposes. Identity politics and conspiracy theories abound, as state-funded media churn out fake news. Given the positive voter feedback regarding all this, we should expect it to continue, they write in Orbán’s Laboratory of Illiberalism, for the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy

A continent-wide process of Orbánisation is under way, according to British political analyst John Gray.

A continent-wide process of Orbánisation is under way, according to British political analyst John Gray.

“Once they are enfranchised, popular majorities resist open borders because they fear the effects on welfare provision and wage levels and demand some say in the overall direction of society. When their protests are ignored by mainstream politicians, they turn to authoritarian leaders,” he writes for The New Statesman.

“The outright dictatorships of the interwar period may not have reappeared, but illiberal democracy is becoming the European norm,” Gray asserts. “Liberal Europe is fading from memory.”

Does conservative support for such illiberal rulers as Poland’s Jaroslaw Kaczynski and Hungary’s Orbán indicate growing “demoskepticism” on the right? Some conservatives now dismiss policies that are infused with democratic values, notes Arch Puddington, distinguished scholar for Democracy Studies at Freedom House:

Does conservative support for such illiberal rulers as Poland’s Jaroslaw Kaczynski and Hungary’s Orbán indicate growing “demoskepticism” on the right? Some conservatives now dismiss policies that are infused with democratic values, notes Arch Puddington, distinguished scholar for Democracy Studies at Freedom House:

Such defenders of Orbán and Kaczyński as John Fonte and James P. Pinkerton argue, among other things, that they are merely asking questions about the effectiveness of liberal democracy in Europe, bucking a suffocating political correctness that emanates from Brussels, standing up for national sovereignty, and carrying out the will of ordinary people whose political needs were ignored by the previous center-left governments.

“But this is clearly not all that they are doing,” he writes for The Weekly Standard.

The July 2018 edition of the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy features an eight-article cluster on rising illiberalism in Central and Eastern Europe, an essay on authoritarian sharp power, and more. The NED’s International Forum asks five leading experts: What is the Root Cause of Rising Illiberalism in Central and Eastern Europe?