The new president of the European People’s Party on Thursday denounced Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s “illiberal” policies and said the status of Orban’s populist party within the influential group will be decided early next year, Associated Press reports (HT:FDD).

Populist/authoritarian regimes are losing legitimacy as members of the urban middle class in places like Hong Kong and Indonesia rise up to protect the political and social freedoms, the New York Times’s David Brooks argues:

These days, it doesn’t take much to set off a giant wave of anger. In Lebanon it was a proposed tax on WhatsApp. In Saudi Arabia the government raised taxes on hookah restaurants. In France, Zimbabwe, Ecuador and Iran it was rising fuel prices. In Chile it was a proposed 4 percent rise in subway fares.

National Endowment for Democracy

The world is unsteady and ready to blow. The overall message is that the flaws of liberal globalization are real, but the populist alternative is not working. The protests in all these places are leaderless, so it’s unrealistic to expect them to have policy agendas. But the big question is, what’s next? What comes after the failure of populism?

“The big job ahead for leaders in almost all these nations is this: Write a new social contract that gives both the educated urban elites and the heartland working classes a piece of what they want most,” Brooks concludes.

Populism is not a coherent ideology, but an umbrella term for parties and movements from across the political spectrum, linked mainly by their vague appeals to working for common folk and opposition to “corrupt elites.” In the fall issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, authors Italo Colantone and Piero Stanig explore another characteristic that many populist parties in western Europe seem to share: economic nationalism. Generally, this refers to tough restrictions on immigration and international trade, combined with conservative economic proposals, the AEA observes:

National Endowment for Democracy

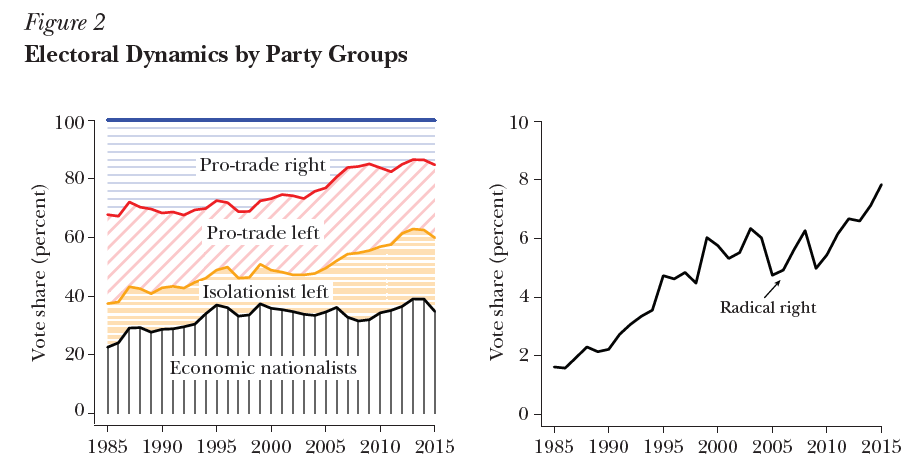

Figure 2 from their paper )above) illustrates the trend toward economic nationalism in western Europe over the past three decades. The left panel breaks down the vote share for four general party categories: economic nationalists (black line), isolationist left (yellow), pro-trade left (red), and pro-trade right (blue). The right panel looks at voter support for 20 parties classified as “radical right.” Together, economic nationalists and isolationist left parties, which include Italy’s Five Star Movement and Greece’s Syriza, have grown from less than 40 percent in 1985 to nearly 60 percent in 2015. Meanwhile, pro-trade political parties have fallen into the minority.

“In other words,” the authors say in the paper, “not only are different populist and antiestablishment parties very heterogeneous in their policy proposals, but the economic factors behind their success also seem to be rather diverse.”

In 1995, the sociologist Ralf Dahrendorf argued that developed countries’ “overriding task” for the subsequent decade was to “square the circle of wealth creation, social cohesion, and political freedom.” More than two decades later, most have not even attempted that feat, notes Helmut K. Anheier, Professor of Sociology at the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin and at Heidelberg University’s Max Weber Institute.

In 1995, the sociologist Ralf Dahrendorf argued that developed countries’ “overriding task” for the subsequent decade was to “square the circle of wealth creation, social cohesion, and political freedom.” More than two decades later, most have not even attempted that feat, notes Helmut K. Anheier, Professor of Sociology at the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin and at Heidelberg University’s Max Weber Institute.

It is time to heed Dahrendorf’s call. This does not mean implementing protectionist policies, which would not only undermine economic growth, but also potentially reinforce authoritarian temptations, given such policies’ link to identity politics. Instead, it requires a comprehensive program comprising proven measures for increasing economic security and social and political engagement, he writes for Project Syndicate: