Recent elections in Spain, Israel and Germany failed to resolve political paralysis and produce governing coalitions. Each country’s situation has its own intricacies and complications. But there are also two general trends that may be leading democracies towards deadlock, writes FT analyst Gideon Rachman:

Recent elections in Spain, Israel and Germany failed to resolve political paralysis and produce governing coalitions. Each country’s situation has its own intricacies and complications. But there are also two general trends that may be leading democracies towards deadlock, writes FT analyst Gideon Rachman:

- The first is the fracturing of two-party systems.

- And the second is the polarisation of politics, with the re-emergence of the far-right and the far-left, and the growing salience of identity issues, which make compromise harder to achieve.

France’s gilets jaunes movement erupted suddenly but has now apparently subsided without leaving a significant impact on electoral politics, argues Patrick Chamorel, a research scholar at the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. Yet the tensions that gave rise to the working-class protests remain strong and are reshaping the political landscape of a divided France, he writes for The Journal of Democracy*:

In part, the Yellow Vest version of populism was a response to the “populism of the elites” embodied by Macron in 2017. The Yellow Vest movement further illustrates the central class and polarized ideological cleavages that shape the politics of a growing number of advanced democracies. …For better or worse, France has always relied on politics to make sense of its collective existence. Faced with a weakening state, a more fragmented society, and increased questioning of the core republican values of universalism, equality, and secularism, France must meet unprecedented challenges.

In part, the Yellow Vest version of populism was a response to the “populism of the elites” embodied by Macron in 2017. The Yellow Vest movement further illustrates the central class and polarized ideological cleavages that shape the politics of a growing number of advanced democracies. …For better or worse, France has always relied on politics to make sense of its collective existence. Faced with a weakening state, a more fragmented society, and increased questioning of the core republican values of universalism, equality, and secularism, France must meet unprecedented challenges.

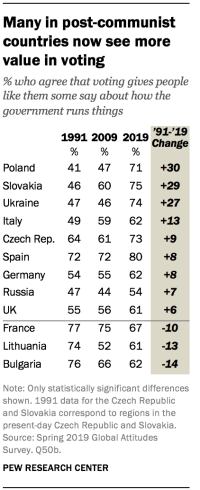

Across Western Europe, only the French are less likely to agree now that voting gives people like them a say than said the same in 1991, though most shifts in opinion have been relatively modest, according to a recent Pew Center poll:

Across most of the countries polled, people with higher levels of education are more likely to agree that voting allows them a say in their countries. For supporters of five right-wing populist parties (AfD in Germany, PVV and FvD in the Netherlands, Vox in Spain and Sweden Democrats in Sweden), those who have favorable views of these right-wing populist parties are less likely to agree, though supporters of both populist parties in Poland, Fidesz supporters in Hungary and OLaNO-NOVA supporters in Slovakia stand apart as exceptions.

Across most of the countries polled, people with higher levels of education are more likely to agree that voting allows them a say in their countries. For supporters of five right-wing populist parties (AfD in Germany, PVV and FvD in the Netherlands, Vox in Spain and Sweden Democrats in Sweden), those who have favorable views of these right-wing populist parties are less likely to agree, though supporters of both populist parties in Poland, Fidesz supporters in Hungary and OLaNO-NOVA supporters in Slovakia stand apart as exceptions.

In a must-read article for the New York Times, Selem Gebrekidan, Matt Apuzzo and Benjamin Novak explain How Oligarchs and Populists Milk the E.U. for Millions.

Europe’s right-wing populists are succeeding in part because they are steering material benefits to working-class supporters, according to Peter Beinart, a professor of journalism at the City University of New York. Poland, like the United States, is divided between young, educated, urban, internationalist cultural liberals and older, rural, nationalist, and nativist cultural conservatives. But unlike the United States, Poland isn’t equally divided between parties of the left and the right; Law and Justice is politically dominant, he writes for the Atlantic:

That dominance may stem in part from the party’s growing control of the press. But there’s more to it than that. The single biggest reason for Law and Justice’s popularity, Aleks Szczerbiak, an expert on Polish politics at the University of Sussex, argued in a blog post last year, is that “the government has delivered on several of the high-profile social spending pledges” it made when first elected, including an initiative that offers every family a monthly subsidy of roughly $125 a child. This program has helped cut Poland’s rate of extreme child poverty from almost 12 percent to less than 3 percent. Law and Justice has also increased payments to the elderly and pledged to hike the minimum wage.

When the US Business Roundtable recently renounced shareholder primacy, the shift – by an organization representing companies with combined annual revenue of more than $7 trillion – prompted a wide range of reactions, from welcoming to dismissive. But the move is primarily an attempt to keep activist shareholders and populist politicians at bay, argues Harvard Law School professor Mark Roe.

When the US Business Roundtable recently renounced shareholder primacy, the shift – by an organization representing companies with combined annual revenue of more than $7 trillion – prompted a wide range of reactions, from welcoming to dismissive. But the move is primarily an attempt to keep activist shareholders and populist politicians at bay, argues Harvard Law School professor Mark Roe.

The relevance of such political considerations is even more pronounced in the United Kingdom, where the British Academy is funding a deep and serious rethink of corporate purpose, led by mainstream academics and business leaders, he writes for Project Syndicate:

*A publication of the National Endowment for Democracy.

Yet, perhaps we should not be overly cynical. Surely not all the US CEOs who backed the Business Roundtable’s statement regarded it purely as a matter of political calculation, or as an opportunity to angle for advantage. Some, perhaps even many, have absorbed some of the values reflected in the new criticism. Business executives constantly have to adapt to changing environments – whether that change is of consumer preferences, technological demands, or political currents.