When Yevgeniy Prigozhin, the head of the Wagner mercenary group, launched his attempted mutiny on the morning of June 24, Vladimir Putin was paralyzed and unable to act decisively, according to Ukrainian and other security officials in Europe, Catherine Belton, Shane Harris and Greg Miller write for The Washington Post:

Russia has deployed private mercenary groups as a shadow arm of the state to protect Kremlin interests, “where the state is without strength or cannot officially act,” according to a report drawn up for a Russian parliamentary roundtable on legalizing the private paramilitary organizations in 2015. The report was obtained by the Dossier Center, an investigative group founded by Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the exiled Putin opponent, and shared with The Post.

“Private paramilitary groups can become effective instruments of state foreign policy,” the report states. “The presence of private military groups in the planet’s ‘hot spots’ will increase Russia’s sphere of influence, win new allies for the country and allow the obtaining of additional interesting intelligence and diplomatic information which ultimately will increase Russia’s weight globally.”

Dossier Center

Putin can simply try to hang on, but given the mounting pressures, he needs a strategy to show that Russia still has a path to victory, notes Lawrence Freedman, Emeritus Professor of War Studies at King’s College London and the author of Command: The Politics of Military Operations From Korea to Ukraine. What Putin does should in turn shape Ukrainian actions, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

Kyiv can add to the anxieties in Moscow, demonstrating that no part of Russia is secure, punishing Russian forces at the front and opportunistically liberating territory even if it is not quite what military planners intended. This has become a war of endurance. Just as Putin must hope that Ukraine and its Western supporters will tire before Russia does, Ukraine and its backers must show that they can cope with the war’s demands for as long as necessary.

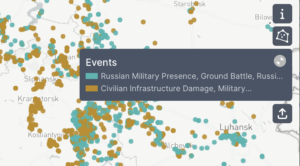

Bellingcat

The sad fact is that today’s Russia is run by war criminals. Equally unfortunate is that most Russians are indifferent to the war crimes their leaders and soldiers are committing daily in Ukraine. But there is hope, adds Alexander J. Motyl, a professor of political science at Rutgers University-Newark.

When war criminals fight war criminals with the methods of war criminality, the consequences are likely to be bloody — and profoundly unstable, he writes for The Messenger. Ordinary Russians will have to abandon their fence-sitting, and Ukraine and the world will have to prepare for a Russian civil war.

The most sobering lesson of the Wagner Group mutiny is that Prigozhin treated Putin the same way that Putin has treated the West, notes Dina Khapaeva, Professor of Russian at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and the author of Crimes sans châtiment (Crimes without Punishment). Prigozhin’s march on Moscow and his hysterical aggression against his nemesis, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, recalls a mobster’s effort to scare his victim into compliance with escalating threats.

The West has contributed to this dynamic by focusing excessively on Putin and giving him too much sway over global affairs, she writes for Project Syndicate:

This was partly a consequence of the Kremlin’s corruption of Western politicians and intellectuals, who downplayed his authoritarianism and positioned Russia as a modern state and reliable energy partner. Even today, despite Russia’s war crimes, Western media often refer to Russia’s elite with the blind objectivity reserved for the powerful, rather than conveying their essential criminality.

The sobering lesson of #Prigozhin’s mutiny is that he treated Putin as #Putin treated the West, whose politicians & intellectuals downplayed his authoritarianism & positioned Russia as a modern state & reliable partner, #DinaKhapaeva writes @ProSyn. https://t.co/BggPybxwKG

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) July 18, 2023

Since the dawn of the 21st century, Russia has rooted itself in two forms of imperialism — Soviet and Tsarist-Russian, neither of which is compatible with ideas of inalienable rights, like life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, says Elena Davlikanova (above), a Democracy Fellow with the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA). The Russian empire offers strong-arm control instead of rights and freedoms and a culture that romanticizes death for the “Greatness of the Motherland” amid endless (and to outsiders) senseless suffering.

While Russian authorities teach their people to die, promising them heavenly paradise in exchange, Ukrainians have sought to build, if not paradise on Earth, a European country that puts human beings at the center of its value system, Davlikanova adds.

While Russian authorities teach their people to die, promising them heavenly paradise in exchange, Ukrainians have sought to build, if not paradise on Earth, a European country that puts human beings at the center of its value system, Davlikanova adds.

In his 2022 op-ed for the London School of Economics, Lucian Leustean wrote that the War in Ukraine was the first Religious War of the 21st century; moreover, a year later he added that “the shifting frontline between Russian and Ukrainian troops can be seen as a religious border,” notes Ilia State University analyst Kristine Margvelashvili.

As religious actors and communities are increasingly active in the public space, there is a risk of religion being used to exclude and not to unite. This is even more so when the political framework in which they operate is authoritarian and not democratic, she writes for the Italian Institute for International Relations (ISPI):

The Compatibility of Orthodoxy and democracy has been long debated, but two observations must be mentioned here, namely that in the 2022 Democracy Index report by the Economist Intelligence Unit none of the Orthodoxy majority states were fully democratic, while Greece, Cyprus, Romania, and Serbia were scored as flawed democracies and the rest of the Orthodox world was either a Hybrid or an Authoritarian regime.

Private mercenary groups act as a shadow arm of the state to protect Kremlin interests, “where the state is without strength or cannot officially act,” says a report obtained by the @khodorkovsky_en-funded @dossier_center, @washingtonpost reports. https://t.co/03C602Nf5K

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) July 25, 2023