Kemal Kilicdaroglu, main challenger of Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan, said on Friday his party has concrete evidence of Russia’s responsibility for the release of “deep fake” online content ahead of Sunday’s presidential elections, Reuters reports.

Turkey is poised to hold an election that could prove decisive not only for the country’s democracy, but also for Europe and the Middle East, DW News reports (above). And most especially for the leader who’s been in power for the past 20 years. Recep Tayyip Erdogan is facing his most contested election ever – with a very real chance of defeat. Some voters are put off by the President’s increasingly authoritarian rule but for many, it’s the economy.

Facing an unusually unified opposition, Erdogan is vulnerable, The Post reports:

Facing an unusually unified opposition, Erdogan is vulnerable, The Post reports:

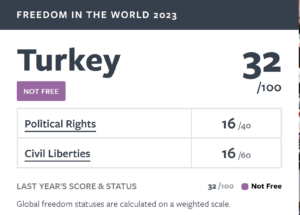

Still, he has imprisoned critics and essentially controls the Turkish media — and U.S.-based watchdog organization Freedom House ranks Turkey as “not free.” ….Voting is compulsory in Turkey — though the fine for not voting is unenforced — and turnout surpasses that of most countries, reaching 86 percent in 2018.

“Turkey has a very long track record of holding competitive elections,” said Merve Tahiroglu, Turkey program director at the Project on Middle East Democracy. “So for people from all walks of life, it’s a bare minimum that the country should have a free enough election where people feel, ‘We’ve picked our leader.’”

The high stakes and the narrow polling gap between the two main candidates have led to speculation that Mr Erdogan may interfere with the elections, challenge the results if he loses or even refuse to abide by them, The Economist reports. Turkey’s strongman has not allayed these concerns. “My people will not hand over this country to a president supported by [terrorists],” he said on May 1st. The interior minister, Suleyman Soylu, has claimed that the election could become “a political coup attempt backed by the West”.

Then there is the question of what Mr Erdogan will do if the votes go against him, The Economist adds. Senior AK officials reject any suggestion that the president would refuse to hand over power. But scores of people with a lot to lose, including corrupt officials and crony businessmen who rely on state contracts, may try to persuade him to hold on to it, especially in case of a narrow loss.

Then there is the question of what Mr Erdogan will do if the votes go against him, The Economist adds. Senior AK officials reject any suggestion that the president would refuse to hand over power. But scores of people with a lot to lose, including corrupt officials and crony businessmen who rely on state contracts, may try to persuade him to hold on to it, especially in case of a narrow loss.

To do this Mr Erdogan would need the backing of the bureaucracy and security forces, says Gonul Tol, an analyst at the Middle East Institute, a Washington-based think-tank. “But that’s a risky scenario for him,” she says. “I don’t think the institutions will back an Erdogan who has just lost an election, because they don’t want to risk legal repercussions [in case the opposition prevails].”

The 2023 Turkish General Election takes place on May 14th.

This week’s #infographic looks at the upcoming general election. pic.twitter.com/Yl721QgC6Z

— The Soufan Center (@TheSoufanCenter) May 5, 2023

“Turkey’s election is situated in the wider global contest between democracy and authoritarianism. If @kilicdarogluk wins, it will be seen as a victory for democracy,” @ChathamHouse expert @GalipDalay tweeted. @CH_MENAP

Glimpses of an alternative, more pluralistic vision, have been discernible in the case of ‘democratic enclaves’ such as the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (İBB), Spyros A. Sofos writes for the LSE. More recently, a similar approach to democracy has been visible in the discourse of main presidential challenger and leader of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), Kemal Kiliçdaroğlu who – setting aside his party’s past repressive and authoritarian leanings and distrust towards minorities – has extended his solidarity towards Turkey’s Kurdish citizens and indicated that his vision of Turkey will be one of openness to difference.

The erosion of media freedom in Turkey has been well documented, notes analyst Lucinda Jordaan. In June 2022, the Project on Middle Eastern Democracy – a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) – presented a detailed snapshot of Turkey’s media landscape, highlighting implications not only for a free and fair press, but also for the upcoming elections.

The erosion of media freedom in Turkey has been well documented, notes analyst Lucinda Jordaan. In June 2022, the Project on Middle Eastern Democracy – a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) – presented a detailed snapshot of Turkey’s media landscape, highlighting implications not only for a free and fair press, but also for the upcoming elections.

“As Turkey plunges into a fraught campaign period ahead of critical elections… Erdoğan and his government face growing public discontent and increasing awareness among the electorate that the country’s economic and political crises are largely of Erdoğan’s own making. As this pressure on the president grows, so will the government’s desire to tame or silence Turkey’s independent journalists.”

The sit-in at Gezi Park in 2013, when 22 people were killed and thousands injured is seen as central to Turkey’s autocratic change of direction and detailed extensively in a new documentary, The Irish Times adds.

The sit-in at Gezi Park in 2013, when 22 people were killed and thousands injured is seen as central to Turkey’s autocratic change of direction and detailed extensively in a new documentary, The Irish Times adds.

At a later political rally, Erdoğan answers his own question about the violence at Gezi. “Who gave the order to the police? Yes, it was me,” he says with pride.

“Democracy is like a tram. You ride it until you arrive at your destination, then you step off,” Erdogan said in the 1990s.