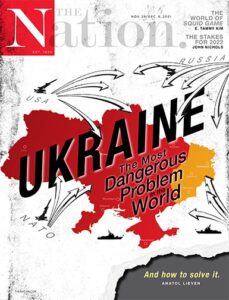

Perhaps the most tragic aspect of the seemingly unending Donbas dispute is that, while it may be one of the most dangerous crises in the world today, it is also in principle the most easily solved, claims Anatol Lieven, a senior research fellow of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. The “Minsk II” agreement drawn up by France, Germany, Russia, and Ukraine and endorsed by the US, the European Union, and the United Nations corresponds to democratic practice, international law and tradition, and America’s own past approach to the settlement of ethnic and separatist conflicts, he writes for The Nation:

Perhaps the most tragic aspect of the seemingly unending Donbas dispute is that, while it may be one of the most dangerous crises in the world today, it is also in principle the most easily solved, claims Anatol Lieven, a senior research fellow of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. The “Minsk II” agreement drawn up by France, Germany, Russia, and Ukraine and endorsed by the US, the European Union, and the United Nations corresponds to democratic practice, international law and tradition, and America’s own past approach to the settlement of ethnic and separatist conflicts, he writes for The Nation:

The United States, of course, has a federal system, as do Canada, Australia, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, India, and South Africa. There can thus be no objection from democratic principle to a federal system for Ukraine, or to special autonomy for the Donbas. Given the vast differences in language and culture between different parts of Ukraine, a federal constitution would seem the best political system for the country as a whole. Failing that, “asymmetric federations,” in which certain regions enjoy special status or one autonomous region exists in an otherwise unitary state, are also an accepted part of certain democracies.

It would indeed be good for Russia’s relations with the United States (and Europe) to be more stable and predictable, as the Biden administration has characterized its short-term objective with the Kremlin, notes Atlantic Council expert Daniel Fried. But that’s not where things are. This has become clear with the Belarusian manipulation of migrants at the Polish border and with the Russian military build-up on the border with Ukraine, he writes for Just Security:

It would indeed be good for Russia’s relations with the United States (and Europe) to be more stable and predictable, as the Biden administration has characterized its short-term objective with the Kremlin, notes Atlantic Council expert Daniel Fried. But that’s not where things are. This has become clear with the Belarusian manipulation of migrants at the Polish border and with the Russian military build-up on the border with Ukraine, he writes for Just Security:

It’s not clear whether Russia’s authoritarian President Vladimir Putin instigated Lukashenka’s human trafficking gambit. But Putin is Lukashenka’s backer and, whatever Putin’s differences with (and reported dislike of) Lukashenka, the spectre of a democracy movement succeeding in ousting an authoritarian next door must seem anathema and an alarming precedent for Russia itself.

Europeanizing Ukraine

Russia’s belligerence has intensified fears that the Kremlin will exploit the Nord-Stream pipeline to undermine Ukraine and as a form of weaponized leverage over the European Union.

But no serious explanation has ever been given of why eastern Ukraine should in recent years have supposedly become so strategically important, the Quincy institute’s Lieven notes. The advocates of bringing Ukraine into NATO also forgot, or never learned, a rule of geopolitics: In the end, all real power is to be judged not on a global and absolute basis but on a local and relative one. That is, it depends on the degree of power that a state is willing and able to bring to bear on a given issue versus that which a rival state is willing and able to commit, he asserts:

But no serious explanation has ever been given of why eastern Ukraine should in recent years have supposedly become so strategically important, the Quincy institute’s Lieven notes. The advocates of bringing Ukraine into NATO also forgot, or never learned, a rule of geopolitics: In the end, all real power is to be judged not on a global and absolute basis but on a local and relative one. That is, it depends on the degree of power that a state is willing and able to bring to bear on a given issue versus that which a rival state is willing and able to commit, he asserts:

Ukrainian politicians might wish to study the examples of Finland, Sweden, and Austria during the Cold War. These states lost nothing through neutrality and developed as prosperous, law-abiding, democratic Western societies that were able to join the EU after the Cold War ended. They could achieve this not through an EU or NATO accession process but rather because the elites and populations of these countries were genuinely committed to democracy, the rule of law, and regulated market economics.

A Europeanizing Ukraine would be good for Russia. But it would be bad for Putinism and, thus, in the Kremlin’s view, needs to be stopped, adds the Atlantic Council’s Fried, a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). The transatlantic community needs to push back on the vectors of aggression from Lukashenka against Poland and the EU and from Putin against Ukraine, using tools of political solidarity, sanctions, and – carefully – military support. The United States, Europe, and likeminded partners should frame the issue jointly and in clear terms:

A Europeanizing Ukraine would be good for Russia. But it would be bad for Putinism and, thus, in the Kremlin’s view, needs to be stopped, adds the Atlantic Council’s Fried, a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). The transatlantic community needs to push back on the vectors of aggression from Lukashenka against Poland and the EU and from Putin against Ukraine, using tools of political solidarity, sanctions, and – carefully – military support. The United States, Europe, and likeminded partners should frame the issue jointly and in clear terms:

- On Belarus, responsibility for the border tensions lies with Lukashenka, and the transatlantic community will neither be bullied into abandoning Belarus democracy or walk away from Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus’s other EU and NATO neighbors;

- On Ukraine, Putin needs to back off his military and energy threats and negotiate an end to the conflict in eastern Ukraine. RTWT

Ukraine vs Russia: War for Democracy

Speaker(s): Oleksiy Honcharuk, Former Prime Minister of Ukraine, Bernard and Susan Liautaud Visiting Fellow at FSI; Kathryn Stoner, Mosbacher Director of Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law is housed in the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. November 16, 2021 4:00 PM – 5:30 PM RSVP Required. Hybrid event: Online via Zoom, and in-person in Bechtel Conference Center. FSI Contact Amye Whalen awhalen1@stanford.edu

This is not a migrant crisis. It is an act of aggression by Lukashenka, using migrants & creating their humanitarian plight for leverage, @AmbDanFried writes for @JustSecurity https://t.co/Ui65npZQ8C

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) November 15, 2021