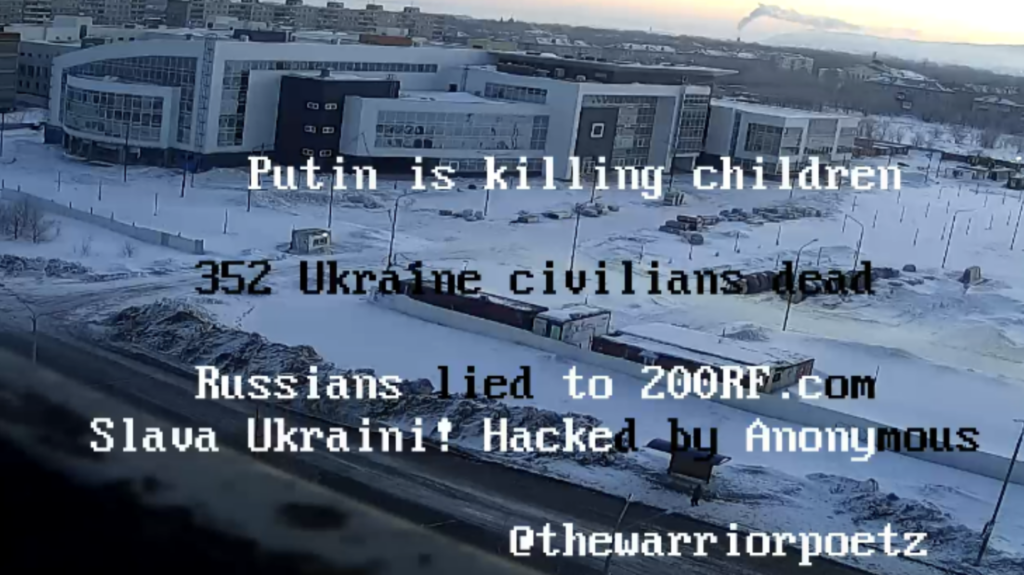

A hacked camera feed in Russia (Anonymous image/Screen grab)

The hacking collective Anonymous has launched a global digital army – the #OpRussia cyber offensive – to counter Kremlin disinformation ops by sending more than 5 million text messages to Russian cell phone numbers relaying information about what’s really happening in Ukraine, reports suggest.

A US military report, “The Little Green Men”, observes that “Russian information warfare has emerged as a key component of Russian strategy,” but Ukrainian soldiers and civilians who spoke with Jigsaw, a research and development unit at Google’s parent Alphabet, seemed ill-equipped to fight cyber attacks, The FT’s Gillian Tett reports:

“You had these soldiers with a few Sim cards on cheap phones but it was very unsophisticated. It felt like no match at all,” Yasmin Green, a Jigsaw official, recalls. Alphabet later offered digital tools to Ukraine, such as Project Shield, to help citizen groups counter cyber attacks that suppress or distort information. ….. But [now] Kyiv has dominated the messaging war. That is startling given how successful Russian disinformation and manipulation campaigns were in the past decade… As Green at Jigsaw observes: “When I think of what I saw in 2018 and what has happened now, I feel quite choked up.”

“You had these soldiers with a few Sim cards on cheap phones but it was very unsophisticated. It felt like no match at all,” Yasmin Green, a Jigsaw official, recalls. Alphabet later offered digital tools to Ukraine, such as Project Shield, to help citizen groups counter cyber attacks that suppress or distort information. ….. But [now] Kyiv has dominated the messaging war. That is startling given how successful Russian disinformation and manipulation campaigns were in the past decade… As Green at Jigsaw observes: “When I think of what I saw in 2018 and what has happened now, I feel quite choked up.”

What explains the turnabout? Tett asks:

- One explanation is that cyber and disinformation attacks work best during “grey” (or undeclared) wars; when fully fledged conflict erupts they become less important. No amount of propaganda is going to win the hearts and minds of a population sheltering from missiles.

- Another may be that Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky, along with some of his advisers, once ran a television production company, so he knows why content creation matters in today’s world.

- But I suspect that a third clue is the reason why Alphabet was in Ukraine in the first place: the long-running war in Donbas made Ukrainian officials acutely aware of the country’s vulnerabilities — and keen to address them with any outside expertise they could find.

What Google knows about the future of war https://t.co/gk8VWtfi76

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) March 9, 2022

Information is at the center of any war and Ukraine’s media has been fighting against Russia’s disinformation war for years, notes Marta Dyczok. But in February 2022, when Putin launched a full-scale military invasion into Ukraine, they were confronted with an entirely new danger.

Journalists and communications infrastructure are being deliberately targeted, along with other civilians, in an effort to silence them. In a remarkable display of unity at all levels—individual, institutional, state, and corporate—Ukraine’s media mobilized and created what can best be described as a common information front to keep society informed and their voices broadcasting, she writes for The Journal of Democracy:

Journalists and communications infrastructure are being deliberately targeted, along with other civilians, in an effort to silence them. In a remarkable display of unity at all levels—individual, institutional, state, and corporate—Ukraine’s media mobilized and created what can best be described as a common information front to keep society informed and their voices broadcasting, she writes for The Journal of Democracy:

To keep society informed, many media outlets soon began running around-the-clock news marathons and pooling resources. In an unprecedented move, three large private corporations—StarLightMedia, 1+1 Media, and Inter Media Group—joined with the public-television broadcaster, UA:First, and Ukrainian Radio to create a common project called United News. Each channel took a slot in the 24-hour news cycle (there was, reportedly, some jockeying for prime positions) for which it would produce a segment of the news that everyone would air. That way, if one company lost its broadcast capability, news would still be broadcast by all the others.

The country’s ‘information warriors’ are on the front line of efforts to maintain the democratic resistance, suggests DyczokUkraine Calling. A Kaleidoscope from Hromadske Radio 2016–2019 (2021).

Within days of the conflict in Ukraine breaking out, Meta, Twitter and YouTube detailed the steps they were taking to reduce information that they deem to be false or misleading. The companies introduced new policies and began labeling and demoting posts from, and containing links to, state-linked Russian media, The Wall Street Journal’s Lisa Linn reports.

EU Stratcom

But Tik-Tok has been less diligent about removing Russia propaganda, say analysts.

“Globally, the platform has become a prominent space for many across the world to view and become informed about the invasion,” said Ciarán O’Connor, a researcher at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue. “But it’s also become an instrument in information warfare too.”

On an internet where propaganda and conspiracy theorizing flourish, you’d expect a land war involving Russia to result in a bewildering barrage of online garbage and falsehoods that render the current state of the conflict truly unknowable, notes Charlie Warzel, the author of Galaxy Brain, a newsletter about the internet and big ideas.

But documentation of the actual military action has emerged with clarity throughout the West, he writes for The Atlantic. Across apps such as Telegram, there are channels with thousands of people—an “army of hackers,” as a Forbes article calls them—attempting to report and take down information from Russian state media and coordinate cyberattacks against Russia.

“There’ve been moments at this early juncture where it’s felt like the first time the information war was won by the disinformation fighters,” said Eliot Higgins, one of the founders of the Bellingcat project. “There is a preexisting network in this region that stretches back to 2014 and that has not gone away,” he said. “Journalists are following this network; policy makers are following it. And so you have videos rapidly geolocated and preserved for war-crimes evidence, and it makes it extremely hard for false Russian narratives to take hold.”

“There’ve been moments at this early juncture where it’s felt like the first time the information war was won by the disinformation fighters,” said Eliot Higgins, one of the founders of the Bellingcat project. “There is a preexisting network in this region that stretches back to 2014 and that has not gone away,” he said. “Journalists are following this network; policy makers are following it. And so you have videos rapidly geolocated and preserved for war-crimes evidence, and it makes it extremely hard for false Russian narratives to take hold.”

Some Westerners ask what value there is to communicating with ordinary Russian citizens when the best hope for affecting Russian policy may be to reach a few key people in the Kremlin, adds Columbia University’s Thomas Kent, a former president of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and a consultant on Russian disinformation issues. The answers are twofold, he writes for the Center for European Policy Analysis:

First, Kremlin leaders cannot eternally ignore public discontent, even if they are willing for now to brutalize anyone who dares protest in the streets. Popular protest and disaffection in Russia may have their effect.

First, Kremlin leaders cannot eternally ignore public discontent, even if they are willing for now to brutalize anyone who dares protest in the streets. Popular protest and disaffection in Russia may have their effect.- Second, the Western world must demonstrate it respects Russia’s population, even if the regime doesn’t. That means showing commitment to the principle that Russians deserve to be informed, and should have a voice in their country’s future.

Much depends on events. If Russia conquers and pacifies Ukraine, the advantage could change again in the information war. But for now, the West has an opportunity — and a responsibility, Kent asserts. RTWT

As Russia targets journalists & communications infrastructure, Ukraine’s information warriors are innovating & collaborating to enhance democratic resilience, @mdyczok @munkschool @KyivMohyla writes for @JoDemocracy https://t.co/mWMNdhbrIe

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) March 9, 2022