IN THE AFTERMATH of a devastating war, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky (above) will have to rebuild and fortify not only Ukraine’s cities and infrastructure but also its democracy, analysts Henry E. Hale and Olga Onuch observe. He will have to end the country’s tendency to shape government around personal patronage networks, which are prone to corruption, and craft an inclusive conception of patriotism. He will also need to respect the rules and the spirit of the Ukrainian constitution.

The Russian invasion rallied Ukraine’s vibrant, inclusive civic nation and strengthened an associated sense of duty and commitment to democracy, they write for Foreign Affairs:

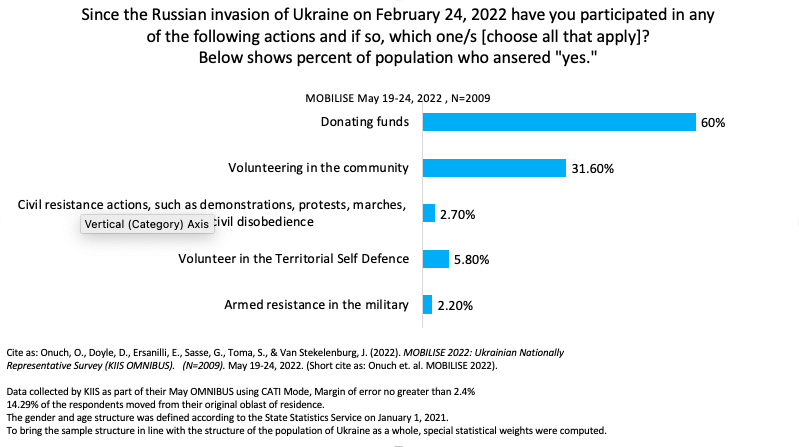

Data collected in February 2023 by the MOBILISE Project (below) showed that approximately 80 percent of Ukraine’s civilian population is involved in the war, through volunteering, protest action, or giving financial support. Others are putting partisan differences aside, uniting in support of the reforms that will be required by EU accession. These positive developments are threatened by Ukraine’s long-standing tradition of what is known as patronalism, which is the feeling that personal connections are necessary to get almost anything done, feeding distrust in the rule of law. …..

The dangers of a return to patronal politics as usual are real, Hale and Onuch – co-authors of The Zelensky Effect – suggest. It cannot be guaranteed that the democratic gains the country has made will be sustained. It is possible, although not highly probable, that Ukraine may shift from the patronal democracy it has typically been in recent years—in which a significant amount of corruption has been leavened by a general commitment to democratic transfers of power when incumbents lose elections—to a more authoritarian or centralized system.

However….

The rise of civic national identity in Ukraine, an identity that places civic duty and attachment to the country above all else, is one of the great achievements of Ukrainian independence. This identity has been elevated and nurtured by Zelensky and consolidated by the war, Hale and Onuch add. Rather, the war seems to have strengthened Ukrainians’ commitment to liberalism and to inclusive ideas of the nation.

“The transatlantic community can only be stable and secure if Ukraine is secure. Ukraine’s entry into NATO, fulfilling the promise made at the 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest, would achieve that,” some 46 foreign policy experts argued in Politico on July 5, GMF reports, a week ahead of the NATO summit in Vilnius, Lithuania.

It’s clear by now that the Summit will not extend an invitation to Ukraine to join the Alliance immediately, says Atlantic Council analyst Daniel Fried, a former Special Assistant and NSC Senior Director for Presidents Clinton and Bush. But there is a good chance that NATO will make the decision that Ukraine, having defended itself against Russian aggression in the name of national survival and the future of its democracy, has clear prospects as a European country and as a member of NATO’s collective defense family.

The issue of Ukraine’s NATO membership is a function of a larger strategic question: is Ukraine a European country and, if it deepens and consolidates its democratic, free-market, and rule-of-law transformation, shouldn’t it be part of the transatlantic community of free and generally prosperous democracies? he writes for Just Security. NATO should see to it that Russia’s aggression, having failed on the battlefield, will not triumph through a cynical diplomatic deal over the heads of the Ukrainians to end the war on Russia’s terms.

Vladimir Putin enjoys support from what Germans dismiss as Putinversteher—sympathisers who “understand” the Russian leader — and what Lenin called “useful idiots”, a cold-war term for unwitting allies of communism, The Economist observes. What seems to link Europe’s far right, far left and “intellectual” opposition to Western policy is something simpler, however. It is a hoary, cold-war-style anti-Americanism.

Vladimir Putin enjoys support from what Germans dismiss as Putinversteher—sympathisers who “understand” the Russian leader — and what Lenin called “useful idiots”, a cold-war term for unwitting allies of communism, The Economist observes. What seems to link Europe’s far right, far left and “intellectual” opposition to Western policy is something simpler, however. It is a hoary, cold-war-style anti-Americanism.

Washington’s favorite ‘realist’ John Mearsheimer consistently gets it wrong, says Rutgers professor Alexander Motyl – a contributor to the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy. Ukraine mattered to Russian perceptions, not because of any actual military threat — Ukraine had some 6,000 battle-ready troops in 2014 — but because of the ideological threat the democratic Maidan Revolution posed to Putin’s claims to be a legitimate autocrat, Motyl writes for The Hill.

The success of Israel and Ukraine highlight that democracies can survive through war and tough times, while countries controlled by strongmen prove too weak to carry the burden necessary to survive, one analyst suggests.

Despite the hardships caused by the war, Ukrainians overwhelmingly—95 percent—believe that their country must have a “fully functioning democracy,” Motyl writes for 1945. Moreover, as befits a democratic country with a strong civil society, 64 percent trust journalists to uncover corruption and 44 percent trust civil society organizations to do so.

Indeed, Ukraine’s vibrant civil society has been the driving force of Ukraine’s democratic trajectory and commitment to Euro-Atlantic integration, says the Westminster Foundation for Democracy’s Rob van Leeuwen. Since the Russian invasion, countless volunteers, community-based organisations and spontaneous citizen-led initiatives, many led by women, have contributed to Ukraine’s efforts to withstand Russia’s aggression.

Sadly, civil society is often overlooked. In a recent survey conducted by Chatham House, only 30% of Ukrainian CSOs stated that they were being engaged or actively engaged in recovery efforts by relevant government authorities, he adds, citing WFD’s partnership with the National Democratic Institute (NDI) in convening a roundtable meeting of Ukrainian CSOs to discuss the role of civil society in ensuring a Ukraine’s democratic recovery.

#Ukraine mattered to Russian perceptions because of the #ideologicalthreat the democratic #Maidan Revolution posed to Putin’s claims to be a legitimate autocrat, @AlexanderMotyl – a contributor to the @NEDemocracy’s @JoDemocracy - writes for @thehill. https://t.co/5jaQIpcmhs

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) July 6, 2023