Is democracy in trouble? Nearly 30 years after Francis Fukuyama declared the end of history and the triumph of liberal democracy, this question is no longer outlandish. But current pessimism should be put in context, the Economist reports:

It is a recent reversal after remarkable progress in the second half of the 20th century. In 1941 there were only a dozen democracies; by 2000 only eight countries had never held an election. A broad poll of 38 countries shows that typically four out of five people prefer to live in a democracy.

It is a recent reversal after remarkable progress in the second half of the 20th century. In 1941 there were only a dozen democracies; by 2000 only eight countries had never held an election. A broad poll of 38 countries shows that typically four out of five people prefer to live in a democracy.

On the downside, a recent study by the German foundation Bertelsmann Stiftung found that 3.3 billion people live under autocratic regimes, while the UK-based Economist Intelligence Unit found that just 4.5 percent of the global population, around 350 million people, live in a “full democracy,” Der Spiegel notes:

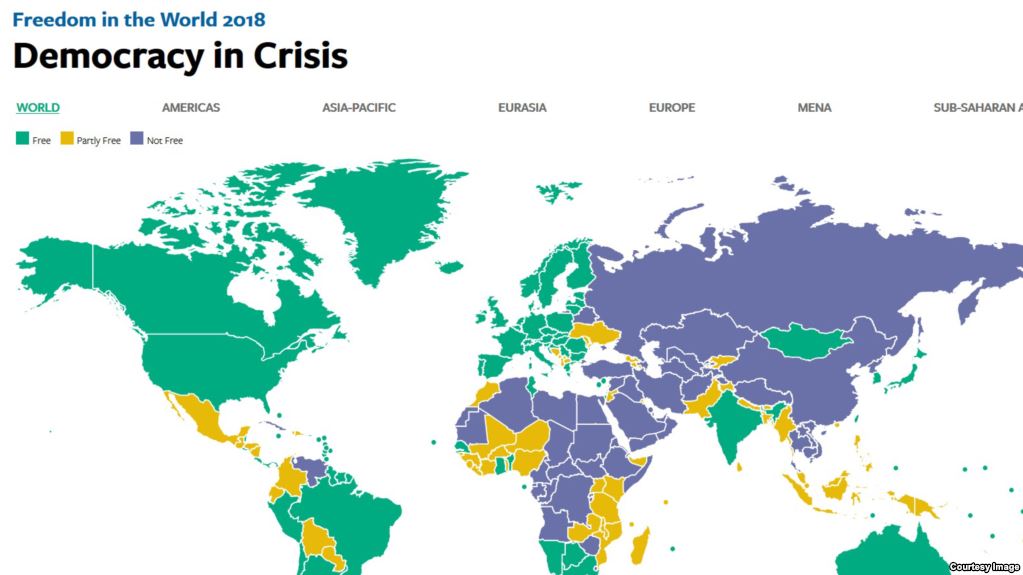

In its most recent annual report, issued in January of this year, the nongovernmental organization Freedom House [above] wrote that in 2017, “democracy faced its most serious crisis in decades.” ….American political scientist Larry Diamond refers to the finding that the number of functioning democracies is shrinking again as the “Democratic Recession.” But why? “The most important and pervasive answer is, in brief, bad governance,” he wrote in a January 2015 essay in the [National Endowment for Democracy’s] Journal of Democracy.

In its most recent annual report, issued in January of this year, the nongovernmental organization Freedom House [above] wrote that in 2017, “democracy faced its most serious crisis in decades.” ….American political scientist Larry Diamond refers to the finding that the number of functioning democracies is shrinking again as the “Democratic Recession.” But why? “The most important and pervasive answer is, in brief, bad governance,” he wrote in a January 2015 essay in the [National Endowment for Democracy’s] Journal of Democracy.

Put crudely, newish democracies are typically dismantled in four stages, the Economist adds:

- First comes a genuine popular grievance with the status quo and, often, with the liberal elites who are in charge. Hungarians were buffeted by the financial crisis and then terrified by hordes of Syrian refugees passing through en route to Germany. Turkey’s pious Muslim majority felt sidelined by secular elites.

- Second, would-be strongmen identify enemies for angry voters to blame. Mr Putin talks of a Western conspiracy to humiliate Russia. President Nicolás Maduro blames America for Venezuela’s troubles; Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orban, blames George Soros for his country’s.

Third, having won power by exploiting fear or discontent, strongmen chisel away at a free press, an impartial justice system and other institutions that form the “liberal” part of liberal democracy—all in the name of thwarting the enemies of the people. They accuse honest judges of malfeasance and replace them with stooges, or unleash tax inspectors on independent television stations and force their owners to sell.

Third, having won power by exploiting fear or discontent, strongmen chisel away at a free press, an impartial justice system and other institutions that form the “liberal” part of liberal democracy—all in the name of thwarting the enemies of the people. They accuse honest judges of malfeasance and replace them with stooges, or unleash tax inspectors on independent television stations and force their owners to sell.- Eventually, in stage four, the erosion of liberal institutions leads to the death of democracy in all but name. Neutral election monitors are muzzled; opposition candidates locked up; districts gerrymandered; constitutions altered; and, in extreme cases, legislatures emasculated.

These similarities hold some lessons, the Economist adds:

- The main one is that institutions matter. Western democracy-promotion has often focused on the quality of elections. In fact, independent judges and noisy journalists are democracy’s first line of defence. Donors and NGOs should redouble their efforts to support the rule of law and a free press, though autocrats will inevitably accuse those whom they help of being foreign agents.

The second is that the reversals have been driven by opportunistic strongmen rather than the voters’ embrace of illiberal ideology. That ultimately makes these regimes brittle. When autocrats steal too brazenly, no censor can stop people from knowing—and sometimes booting them out.

The second is that the reversals have been driven by opportunistic strongmen rather than the voters’ embrace of illiberal ideology. That ultimately makes these regimes brittle. When autocrats steal too brazenly, no censor can stop people from knowing—and sometimes booting them out.- The last, more uncomfortable lesson is that the example set by mature democracies matters…..