The compulsory hijab law is perhaps the most high-profile of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s many human and civil rights violations. Yet for Masih Alinejad (above, addressing the National Democratic Institute’s 30th Anniversary Gala), it is much more than that – it is “the most visible symbol of oppression.” It is this conviction that has led her to become one of the most prominent figures in Iranian activism, leading a charge from exile in New York using social media, writes Jeremie Langlois, a research associate with the National Endowment for Democracy’s Reagan-Fascell Fellowship Program.

After a decade-long career as a hard-hitting reformist journalist in Tehran, Masih rose to international prominence in 2014 when she posted a picture of herself in London without a hijab, with a short caption musing about how she treasured her freedom to do so. Soon after, she posted another unveiled portrait, this time an old photo taken in a car in Iran. The results were explosive. Thousands of Iranian women began to send her photos of themselves unveiled, asking Masih to post them to her Facebook page.

Credit: My Stealthy Freedom Facebook

Masih’s My Stealthy Freedom attracted over a million followers, spawning hashtags like #mycameraismyweapon and #whitewednesdays. The latter has grown into one of the most problematic protest movements for the Iranian regime, featuring women removing their hijabs in public, posting videos to social media, and thousands of women across the country wearing white on Wednesdays in solidarity.

The Iranian government responded with an elaborate smear campaign against Masih, and attempts to crack down on White Wednesday protesters. The harsh reaction raises the question, what makes the movement so threatening? For experts like Karim Sadjadpour of the Carnegie Institute for International Peace, the Islamic Republic’s rhetoric of “Death to America, Death to Israel, and mandatory hijab” isn’t just about political posturing, it articulates the organizing principles that define the regime, he explained at a recent Georgetown University discussion. Azar Nafisi, author of Reading Lolita in Tehran, concurred saying, “The hijab in Iran is not about religion. It is about an ideology in order to preserve power. It is uniformity. It is like the Mao jackets that people wore in the Republic of China.”

The threat the movement poses may also have to do with the identity of its supporters. The complex cleavages that have long defined Iranian society do not seem to matter. In a highly diverse country, My Stealthy Freedom has been exceptional in attracting women from across regions, economic classes, and social circles. Moreover, the movement is not just for women. In 2016, Masih, using the #meninhijab, called on male allies to don headscarves in solidarity with their female friends and loved ones. As she noted, “Most of these men are living inside Iran and they have witnessed how their female relatives have been suffering at the hands of the morality police and humiliation of enforced hijab.”

The threat the movement poses may also have to do with the identity of its supporters. The complex cleavages that have long defined Iranian society do not seem to matter. In a highly diverse country, My Stealthy Freedom has been exceptional in attracting women from across regions, economic classes, and social circles. Moreover, the movement is not just for women. In 2016, Masih, using the #meninhijab, called on male allies to don headscarves in solidarity with their female friends and loved ones. As she noted, “Most of these men are living inside Iran and they have witnessed how their female relatives have been suffering at the hands of the morality police and humiliation of enforced hijab.”

Masih’s My Stealthy Freedom movement has been exceptional not only in its popularity and in subversive impact, but also in how it blurs boundaries between so-called women’s issues and the universal struggle for freedom, and between online activism and public disobedience in the physical space.

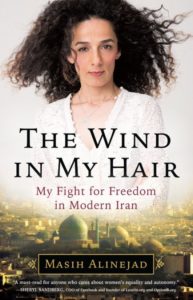

Masih’s recent book The Wind in My Hair is “the story of modern Iran, the tension between its population and the forced Islamization of society, especially young women, for their rights against the introduction of Sharia law, against violations of human rights and civil liberties,” she writes. My Stealthy Freedom offers a platform for millions of Iranians that is relatable, divorced from specific political parties or ideologies, and visible on the world stage – a potent combination that could define contentious politics in Iran for years to come.

Credit: Stealthy Freedom Facebook