Credit: FT

Larry Diamond of Stanford University has argued that liberal democracy has four necessary and sufficient elements: free and fair elections; active participation of people, as citizens; protection of the civil and human rights of all citizens; and a rule of law that binds all citizens equally. The salient feature of the system is the restraints it imposes on the government and so on the majority: any victory is temporary, The FT’s Martin Wolf writes.

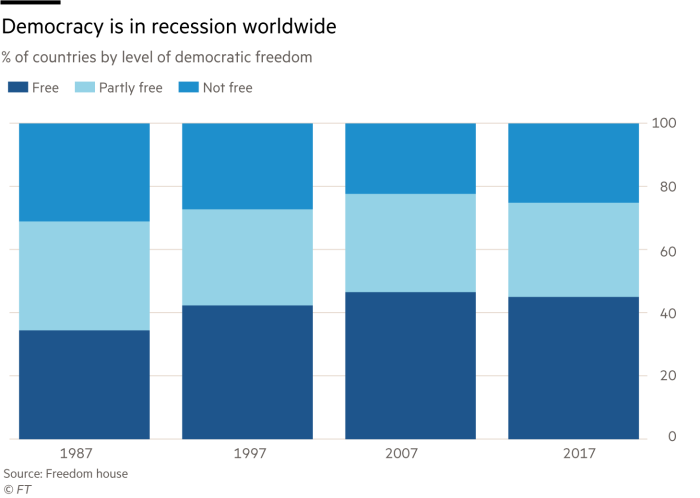

But how far does such undemocratic liberalism explain illiberal democracy? The answer is: it does, up to a point, he adds, citing Freedom House’s 2018 report:

But how far does such undemocratic liberalism explain illiberal democracy? The answer is: it does, up to a point, he adds, citing Freedom House’s 2018 report:

A view that the economic dimension [see below] of undemocratic liberalism has driven the people towards illiberal democracy is exaggerated. What is true is that poorly managed economic liberalism helped destabilise politics. That helps explain the nationalist backlash in high-income countries. Yet the kind of illiberal democracy we see in Hungary or Poland, which is rooted in their specific histories, is not an inevitable outcome in established democracies.

In the 2017 report Sharp Power: Rising Authoritarian Influence, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) identified the subtle effect of the strategic use of soft power tools by authoritarian states on democratic institutions worldwide, notes Andrew Wilson, Executive Director of the Center for International Private Enterprise. Corrosive capital, in its higher states of “acidity,” has become an effective instrument to complement these efforts. Consequently, there is a pressing need in weak democracies for local projects that reduce the disruptive effects of corrosive capital, he writes in the preface to a new report, Channeling the Tide: Protecting Democracies Amid a Flood of Corrosive Capital.

In the 2017 report Sharp Power: Rising Authoritarian Influence, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) identified the subtle effect of the strategic use of soft power tools by authoritarian states on democratic institutions worldwide, notes Andrew Wilson, Executive Director of the Center for International Private Enterprise. Corrosive capital, in its higher states of “acidity,” has become an effective instrument to complement these efforts. Consequently, there is a pressing need in weak democracies for local projects that reduce the disruptive effects of corrosive capital, he writes in the preface to a new report, Channeling the Tide: Protecting Democracies Amid a Flood of Corrosive Capital.

Democratic capitalism is showing signs of deep, systemic sickness in the United States, Europe and Australasia, even as varieties of state or authoritarian capitalism are slowly becoming entrenched around the world, particularly in China and Russia, notes former Australian premier Kevin Rudd. Nevertheless, there is something elementally powerful about the underlying idea of individual dignity and freedom, he writes for the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs:

Despite the baggage of colonialism, democratic capitalism succeeded remarkably in Asia, Africa and Latin America after World War II, and after the Cold War in particular. The democracy watchdog group Freedom House reports that as of 2017, 88 of 195 states were classified as “free,” compared with 65 of 165 in 1990.

Despite the baggage of colonialism, democratic capitalism succeeded remarkably in Asia, Africa and Latin America after World War II, and after the Cold War in particular. The democracy watchdog group Freedom House reports that as of 2017, 88 of 195 states were classified as “free,” compared with 65 of 165 in 1990.

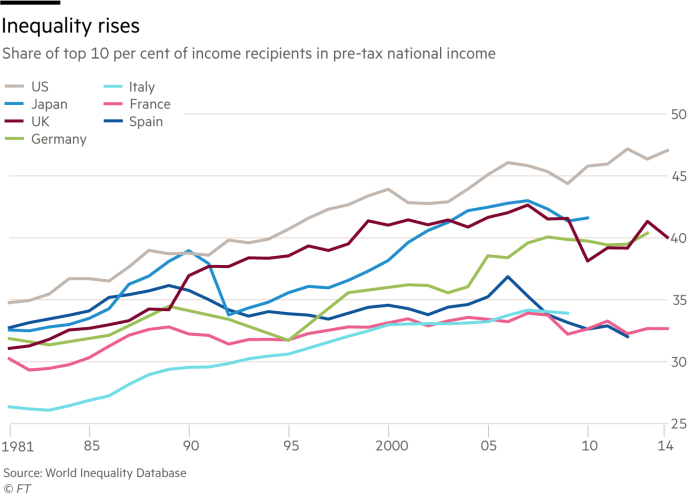

After the end of the Cold War, however, four structural challenges emerged to endanger the future of democratic capitalism: financial instability, technological disruption, widening social and economic inequality and structural weaknesses in democratic politics. If the West cannot overcome these challenges, they will, over time, spread to the rest of the world and undermine open polities, economies and societies.