The uprisings of the Arab Spring seemed to represent a dramatic turning point in history, the sudden collapse of regimes and political systems few expected to be so fragile. But the years since showed how much of the prevailing order endured, the Post’s observes.

“It appeared that decades happened in a few weeks in Tunisia and Egypt, and later in other countries when the tip of the ancient tyrannical pyramid was blown away,” wrote Hisham Melhem, a veteran analyst of Middle East politics. “[Former Tunisian leader Zine el-Abidine] Ben Ali, Mubarak, and others have gone, but the pyramid — more broadly the political, economic, and security structure and the cultural superstructures that supported these modern-day pharaohs and allowed them to torment their societies — is still intact.”

Democracy isn’t like instant coffee. It needs an enabling environment and a hospitable culture to flourish and grow, argues Nobel Peace Prize laureate Mohamed ElBaradei, the former director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Without a robust and vibrant civil society — labor unions, political parties, associations and independent media — it was impossible to agree on a transitional road map following the swift fall of Arab dictators. The institutions needed to enable true social cohesion were simply not there, he writes for Project Syndicate.

The Arab world has more democratic headroom than many of us give it credit for, according to Tarek Masoud, Professor of International Relations at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. But how might the Arab world deliver on that democratic potential? he asks in the NED’s Journal of Democracy:

The Arab world has more democratic headroom than many of us give it credit for, according to Tarek Masoud, Professor of International Relations at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. But how might the Arab world deliver on that democratic potential? he asks in the NED’s Journal of Democracy:

As a new U.S. administration prepares to take office, we might be tempted to call for renewed pressure on autocrats to respect human rights and even to allow political competition. But if democracy is to come to the Arab world, it will not be because autocrats were hectored into granting it. It will be because democracy won the argument. And for that to happen, ordinary Arabs will need evidence that it can deliver something other than chaos and discord.

The 2011 uprisings have had three main consequences: fear of state collapse, increased social polarization and the increasing importance of socio-economic demands. Any strategy for political change must address these factors in order to be successful, writes Dr Georges Fahmi, Associate Fellow with the Chatham House Middle East and North Africa Program:

- Restoring state institutions in countries where such institutions have either collapsed or have become ineffective, and protecting the state from collapse in other cases, are now important factors that could either hinder or strengthen any project for political change…..

- Addressing social polarization and strengthening citizen trust is important for mobilization. During the first wave of the Arab Spring in 2011, societies were less polarized – politically, religiously and ethnically – than they are today…..Religious and ethnic tensions have also risen in the region since 2011, which plays into the hands of ruling regimes who benefit from social divisions. …

- Any political project for change will need to address ongoing socio-economic grievances. In 2011, protesters made a clear link between political change and addressing socio-economic issues, believing that once authoritarian regimes were brought down, such problems would vanish. This belief no longer exists….RTWT

Despite increased aspirations and political openness after the protests, deep changes to economic governance and outcomes failed to materialize. Why? the World Bank asks (above). Fixing the social contract between citizens and government and creating 300 million more private-sector led jobs are still needed, argues World Bank MENA Vice-President Ferid Belhaj.

Despite increased aspirations and political openness after the protests, deep changes to economic governance and outcomes failed to materialize. Why? the World Bank asks (above). Fixing the social contract between citizens and government and creating 300 million more private-sector led jobs are still needed, argues World Bank MENA Vice-President Ferid Belhaj.

“On the face of it, the Arab Spring failed, and spectacularly so — not only by failing to deliver political freedom but by further entrenching the rule of corrupt leaders more intent on their own survival than delivering reforms,” said the Post’s Liz Sly.

A focus on constraining geopolitical competition within the region, confronting Iranian behavior more effectively, and wielding diplomacy to resolve conflicts where possible should enable Washington to do less and not have its regional dominance threatened, says Brookings analyst Tamara Cofman Wittes, a board member of the National Democratic Institute (NDI). Risks and challenges for American interests remain, and the virus is a reminder of how fragile governance and social services are in too many parts of the Middle East, posing a long-term challenge to stability and security.

“By destroying civil society, coopting institutions, repressing dissent, and blocking even incremental reform, authoritarians in the Arab World have created a trap in which political ruptures are the only path for change,” argued Michael Hanna, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation.

In recent years, new uprisings in Algeria, Sudan, Lebanon and Iraq toppled governments and triggered processes toward political reform whose outcomes are far from certain, especially given that the the root causes of simmering discontent — massive youth unemployment, stagnating economies, endemic corruption and feckless political elites – remain, the Post’s Tharoor adds.

“The status quo is untenable, and the next explosion will be catastrophic,” said Fawaz Gerges, professor of international relations at the London School of Economics. “We’re talking about starvation, we’re talking about state collapse, we’re talking about civil strife.”

The Arab Spring 10 Years On via @ChathamHouse https://t.co/8BXXRpliHX

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) January 26, 2021

Over the past two centuries, many countries have taken significant steps towards democracy only to then de-democratize, at least temporarily. Support for democracy is a fundamental aspect of the Arab Spring – and it is still present, adds Chatham House analyst Fahmi. Despite the mostly negative experience of the last 10 years, the fifth survey of the Arab Barometer has shown that 78 per cent of Tunisians, 74 per cent of Libyans, 70 per cent of Egyptians and 51 per cent of Yemenis still believe that although democratic systems are not perfect, they are the best option. RTWT

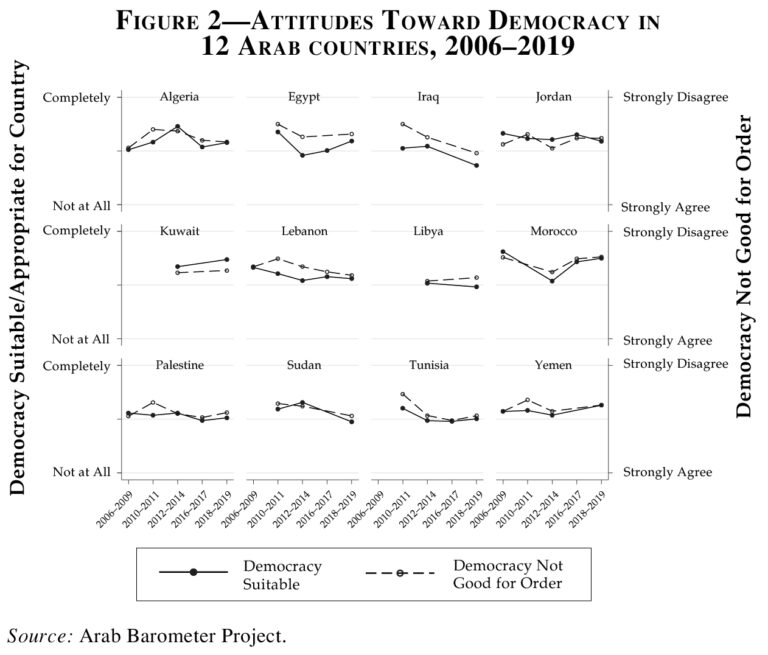

But Harvard’s Masoud is not so convinced. As is clear from Figure 2, (below), in many Arab countries today, enthusiasm for democracy is at a low ebb, he writes for the NED’s Journal of Democracy:

Most alarming, Tunisians seem almost evenly divided about the suitability of democracy for their country, and a sizeable number seem to have accepted the authoritarian talking point that democracy is ineffective at guaranteeing stability and security. In Iraq, Sudan, Algeria, and Lebanon… attitudes toward democracy also seem to trend downward, suggesting that optimism about the ultimate outcomes of mass movements in those countries might be misplaced.

One could be forgiven for inferring from these charts that Arabs have lost faith in democracy, Masoud suggests. RTWT

On the 10th anniversary of the #ArabSpring, join the @CIHRS_Alerts webinar with @MarwanMuasher, Marina Ottaway, @Yassinhs & Yadh Ben Achour. Moderated by @BaheyHassan. Wednesday, Jan. 27th. 15:30 CET Register Here