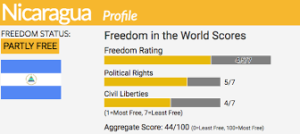

Nicaragua’s opposition National Coalition has announced that it will boycott the November 7 election.

The issue of whether to boycott or participate in authoritarian elections presents democratic actors with a strategic dilemma, but calculations should be driven by circumstances as much as principle, analysts suggest.

Virtually all potential challengers to Nicaraguan president, Daniel Ortega, have disappeared, been detained, or pushed into exile, while the independent media has been silenced and the main opposition party disqualified from running. Yet Ortega continues to keep up the illusion of holding free elections, imitating the tactics of President Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela, the Times reports:

These days, governments like those in Nicaragua, Venezuela and elsewhere that reject political pluralism are ready to go to great lengths to pretend to embrace democracy — primarily by imitating the crucial rituals of periodic elections.

“There is still a desire on the part of regimes to have a fig leaf of democracy, however not credible that is,” said Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue, adding that the pretense might have been the excuse Mexico and Argentina needed to avoid joining in a recent Organization of American States vote denouncing the crackdown against Mr. Ortega’s political rivals in Nicaragua.

“There is still a desire on the part of regimes to have a fig leaf of democracy, however not credible that is,” said Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue, adding that the pretense might have been the excuse Mexico and Argentina needed to avoid joining in a recent Organization of American States vote denouncing the crackdown against Mr. Ortega’s political rivals in Nicaragua.

Hong Kong’s largest pro-democracy party will not contest the upcoming “patriot only” legislature elections, AFP reports. The decision means the December polls have been effectively boycotted by the city’s pro-democracy opposition with even the movement’s most moderate wing deciding it is not worth taking part.

Eighty per cent of eligible voters took part in Uzbekistan’s election, which commentators described as uncompetitive, as the authorities had excluded several opposition figures and independent journalists reported fraud at several polling stations, with pre-filled ballot papers being inserted into the ballot boxes. The blogger and government critic, Valijon Kalonov, was arrested on charges of insulting the president through mass media after he called for a boycott of the upcoming election, Human Rights Watch reports.

POMED

The popular boycott of Algeria’s June parliamentary elections was more important than the results, Adel Ourabah writes for the Arab Reform Initiative. Despite being promoted as a panacea for the country’s structural crises, and an opportunity for the Hirak to integrate elected bodies, they were marred by very low turnout and failed to renew Algeria’s political class.

While elections can sustain autocratic regimes by generating a veneer of legitimacy, electoral mobilization can also boost opposition forces. Some 50 percent of regime collapses or “dictatorship deaths” occur during election years, according to one analysis.

Alongside the legislature, the judiciary, and the media, elections are one of four democratic institutions in competitive authoritarian regimes to provide “arenas of contestation” through which opposition forces may periodically challenge, weaken, and occasionally even defeat autocratic incumbents, argue Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way.

[E]ven if the cards are stacked in favor of autocratic incumbents, the persistence of meaningful democratic institutions creates arenas through which opposition forces may—and frequently do—pose significant challenges, they write in Elections Without Democracy: The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism, an article for the National Endowment for Democracy‘s Journal of Democracy. As a result, even though democratic institutions may be badly flawed, both authoritarian incumbents and their opponents must take them seriously.

In Pathways to Power: Opposition Party and Coalition Building in Multiethnic Malaysia, Sebastian Dettman analyzes how and why opposition parties are able to gain substantial electoral support against the authoritarian odds, citing individual strategies used by parties to win over new voters from the ruling government, and collective strategies, where opposition parties coordinate or build coalitions with each other in elections. Malaysia is an interesting and important case for several reasons, he adds, not least because:

- First, a single party, the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), dominated the country’s ruling coalitions from the country’s independence in 1957 until 2018. But against this backdrop of extraordinary stability, Malaysia’s opposition parties gradually built up electoral power to the point of unseating UMNO from national power for the first time in 2018.

- Second, Malaysia is a country of incredible diversity…This made the challenges faced by the opposition even more pronounced as they sought to expand support across ethnoreligious lines while also building cross-cleavage coalitions.

Iran’s elections are now “meaningless” not only because reform-minded candidates are disqualified, but because the entire process is arbitrary, reformist Mostafa Tajzadeh, a senior aide to former President Mohammed Khatami, declared in a tweet. Despite this, four main obstacles deterred reformists from calling for an official electoral boycott, he told the Carnegie Endowment:

Iran’s elections are now “meaningless” not only because reform-minded candidates are disqualified, but because the entire process is arbitrary, reformist Mostafa Tajzadeh, a senior aide to former President Mohammed Khatami, declared in a tweet. Despite this, four main obstacles deterred reformists from calling for an official electoral boycott, he told the Carnegie Endowment:

- First, Tajzadeh explained that if he could be confident that 10 million people would follow a call to spoil their ballots or write in dissident politicians, then he might have supported such a protest vote. …

- The second reason was that support from other elites for a boycott was also unlikely. ….Even dissident journalists such as Ahmad Zeidabadi have argued that democrats should focus instead on strengthening their social organizations…

- A third driving factor for reformist groups’ hesitancy to call for a boycott is that electoral boycotts in authoritarian settings generally do not work. ..Of the 170 boycotts studied by political scientists over the last three decades, most of them failed to level the unfair electoral playing field, delegitimize the ruling regime’s fraudulent electoral practices in the eyes of the international community, or force the ruling regime to share power with democratic forces or to change. …

- The fourth consideration is that to be effective, a boycott must include civil disobedience (e.g. peaceful street demonstrations) that is too risky inside the Islamic Republic…

Yet as Iranians are aware by now, real authority lies with the Supreme Leader and the regime’s shadowy and unelected bodies, said Masih Alinejad, an Iranian journalist, author and women’s rights campaigner. This has inspired a grassroots electoral boycott campaign—#NotVotingForIR or Ray-bi-ray in Persian— which has received a massive boost from family members of political prisoners and protesters killed during four decades of Islamic governance. All are united in saying that they will not participate in rigged elections.

Yet as Iranians are aware by now, real authority lies with the Supreme Leader and the regime’s shadowy and unelected bodies, said Masih Alinejad, an Iranian journalist, author and women’s rights campaigner. This has inspired a grassroots electoral boycott campaign—#NotVotingForIR or Ray-bi-ray in Persian— which has received a massive boost from family members of political prisoners and protesters killed during four decades of Islamic governance. All are united in saying that they will not participate in rigged elections.

Iran’s civil society has also used boycotts to question the legitimacy of the theocratic regime,

Abdorrahman Boroumand Center (see video above). The international community should recognize the price some have paid to shun the ballot box and help defend Iranians’ right to peaceful activism, it adds.

Successful pre-election boycotts are costly for opposition parties, notes Susan D. Hyde. Not only do successful boycotts involve significant organization, they require that the parties forgo any possibility of representation, she writes in The Pseudo-Democrat’s Dilemma: Why Election Observation Became an International Norm. Threatening or carrying out an election boycott has been used in many countries to draw attention to unfairness in the electoral process, to pressure governments to rectify problems in the administration of elections, and to draw international and domestic attention to election manipulation.

Yet there is a concern that authoritarian elections can corrode the appeal and legitimacy of political participation in any subsequent democracy.

Yet there is a concern that authoritarian elections can corrode the appeal and legitimacy of political participation in any subsequent democracy.

As an ever great proportion of citizens experience elections for the first time in poor quality elections, in any future transitions to democracy, the majority of citizens in these countries may be reluctant and jaded participants in democratic elections, say V-Dem researchers. To put it simply, adjusting from elections as a stage-managed spectacle to a real means of allocating the power to govern may not come easily to today’s authoritarian citizens.

Opposition participation in questionable elections more often generates gradual democratization than boycotting or rejecting the outcome in the same situation, analyst Staffan Lindberg contends. On balance, electoral participation leads to a higher level of democratization, he writes in “Tragic Protest: Why Do Opposition Parties Boycott Elections?”

Electoral engagement is a precondition of democratic renewal, according to a recent Brookings report.

There is no way around it: to win back power, the pro-democracy political opposition must get voters to the polls and must be prepared to counter unfair voter suppression tactics, according to Norman Eisen, Andrew Kenealy, Susan Corke, Torrey Taussig, and Alina Polyakova, the authors of The Democracy Playbook: Preventing and Reversing Democratic Backsliding:

There is no way around it: to win back power, the pro-democracy political opposition must get voters to the polls and must be prepared to counter unfair voter suppression tactics, according to Norman Eisen, Andrew Kenealy, Susan Corke, Torrey Taussig, and Alina Polyakova, the authors of The Democracy Playbook: Preventing and Reversing Democratic Backsliding:

Opposition parties in hybrid states often lose elections partly because citizens opposed to the regime nonetheless abstain from voting due to their frustration with the opposition’s frequent infighting or incompetence. Others are young and are potentially first-time voters. The opposition must tune their messaging to win over both groups, generating new votes.

Recent research investigating 61 competitive authoritarian elections after the end of the Cold War shows that increased voter turnout is directly associated with a larger vote share for the opposition, the Brookings reports adds.

Elections do tend to bring down hybrid leaders, but do not necessarily lead to democracy, recent research suggests. Contesting elections does seem to be more helpful in driving transitions from hybrids to democracy than boycotting.