Belarus’s president, Alexander Lukashenko, facing growing nationwide protests, said he was ready to share power, but only on his own terms, as the main opposition leader said she was ready to lead the Eastern European country, The Wall Street Journal’s Ann M. Simmons writes:

Demonstrators took to the streets in cities and towns around Belarus for a ninth consecutive day Monday, while some state-enterprise workers went on strike, venting their frustration over the country’s disputed Aug. 9 presidential vote…. The Belarusian leader has said he would be willing to hand over power, but only after a referendum and the adoption of a new constitution and not because of street protests.

How will Russia react if Belarus breaks free of the dictator’s shackles? asks Sławomir Sierakowski, a senior fellow at the Alfred von Oppenheim Center for European Policy Studies at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) and the founder and leader of Krytyka Polityczna (Political Critique).

How will Russia react if Belarus breaks free of the dictator’s shackles? asks Sławomir Sierakowski, a senior fellow at the Alfred von Oppenheim Center for European Policy Studies at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) and the founder and leader of Krytyka Polityczna (Political Critique).

It will release its closest ally from its sphere of influence. That does not seem up for debate at all, and yet it is not an obvious point, he writes for Project Syndicate:

I asked a number of excellent experts on the region, both inside Belarus (Valer Bulhakau) and abroad (Adam Michnik and Timothy Snyder), and all agreed that Russia would not intervene. There will be no Ukrainian scenario, because that has simply not paid off for Russia. It gained the Donbass and Crimea—meaning it gained only problems—and lost Ukraine. Before 2014, Ukrainian society was favorable to Russia and largely spoke Russian. Russia had economic influence and an ally. And now the Russian language is disappearing in Ukraine, the economy is slowly recovering, the military is arming, and Russia is the country’s primary enemy in the eyes of Ukrainians. Anyone who claims otherwise is just ashamed to admit it.

Russian President Vladimir Putin makes no secret of his hatred for so-called color revolutions, but there are at least five reasons why he should not intervene to save Lukashenko, writes Council on Foreign Relations expert Stephen Sestanovich (right):

Russian President Vladimir Putin makes no secret of his hatred for so-called color revolutions, but there are at least five reasons why he should not intervene to save Lukashenko, writes Council on Foreign Relations expert Stephen Sestanovich (right):

1. The protests against Lukashenko have virtually no anti-Russia dimension—yet. Ukraine’s Orange Revolution of 2004 and the Euromaidan uprising of 2014 drew on nationalist sentiment: Russia was seen by many as Ukraine’s oppressor, and pro-Russia politicians as agents of colonialism. Earlier political upheavals—including Baltic independence movements in the early 1990s and Georgia’s Rose Revolution of 2003—had varying doses of nationalist fervor. What is happening in Belarus does not.

2. Crushing democracy in Belarus brings Putin no nationalist payoff. Whatever political benefit Putin received from the annexation of Crimea—very significant—and fomenting an insurgency in eastern Ukraine—by now, slight—any actions to prop up Lukashenko will look very different to the Russian public. Intervention will appear to have one motive only: to support electoral fraud and silence the Belarusian people. Coming on the heels of his own sketchy referendum to escape term limits, Putin does not need more trouble.

3. Popular mobilization in Belarus is already far advanced. Nipping demonstrations in the bud is no longer an option. Lukashenko tried a crackdown, and it only spurred more demonstrations. For his part, Putin has spent his summer tolerating ongoing protests in the Far Eastern city of Khabarovsk, sparked by the arrest of the elected regional governor. Putin clearly hoped those demonstrations would eventually go away. When they did not, he realized he would have to tolerate them—and try something else.

3. Popular mobilization in Belarus is already far advanced. Nipping demonstrations in the bud is no longer an option. Lukashenko tried a crackdown, and it only spurred more demonstrations. For his part, Putin has spent his summer tolerating ongoing protests in the Far Eastern city of Khabarovsk, sparked by the arrest of the elected regional governor. Putin clearly hoped those demonstrations would eventually go away. When they did not, he realized he would have to tolerate them—and try something else.

4. “Little green men” cannot solve Putin’s problem. The head of the government media outlet RT, Margarita Simonyan, made news last week when she called for “polite people” (Putin’s smirking term for the irregular Russian troops who seized Crimea, also known as “little green men”) to get involved. But it is extremely unlikely that Russian military, intelligence, or police are telling the Kremlin that pacifying the Belarusians will be a low-cost operation. At this point, they are probably not even sure their Belarusian counterparts would stand with them. If not, intervention would be a nightmare.

5. If “little green men” are no use, the Belarusian elite may be. Even some of Lukashenko’s strongest political opponents want close ties with Russia. The two countries have enough economic, political, and military experience dealing with each other that there is no treason—or even personal discredit—in favoring good relations. These connections to and favorable attitudes within the Belarusian elite give Putin many ways to foster a transition away from Lukashenko.

5. If “little green men” are no use, the Belarusian elite may be. Even some of Lukashenko’s strongest political opponents want close ties with Russia. The two countries have enough economic, political, and military experience dealing with each other that there is no treason—or even personal discredit—in favoring good relations. These connections to and favorable attitudes within the Belarusian elite give Putin many ways to foster a transition away from Lukashenko.

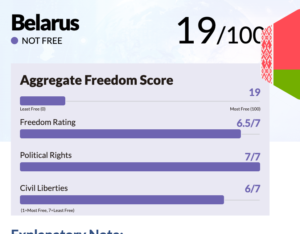

The West — presidents, prime ministers, parliaments, civil society leaders and the media — must not lose interest in this crisis, say Stanford’s Michael McFaul and Florida University’s David J. Kramer. We must continue to focus our attention on the events unfolding in Belarus, and make sure demonstrators fighting for freedom know which side of the barricade we stand on. For more than two decades, Belarus has been written off as the last dictatorship in Europe. (In fact, there are two, the other being Putin’s Russia.) But fed up with Lukashenko, Belarusians have not given up fighting for democracy. When they need us most, we — Democrats and Republicans at home together, democracies around the world united — must not give up on them, they wrote for NBC News.

The EU already said it does not recognize the outcome of the presidential election. The idea of new elections would rattle Putin, whose own record on free and fair elections has been challenged—so far unsuccessfully—by protesters in Russia, adds Judy Dempsey, a nonresident senior fellow at Carnegie Europe and editor in chief of Strategic Europe. Much now depends on when and how Tikhanovskaya returns to Belarus to start a transition that has already started on the streets. The movement needs leadership for Belarus’s turn for change to come.

Lukashenko was heckled by workers on a visit to a factory as anger mounted over his disputed re-election, the BBC reports (below).

Speculating about the possible collapse of the regime in Belarus, we can rule out all scenarios that involve an agreement between Lukashenka and the opposition, adds Sierakowski. The so-called the Spanish road to democracy or a round table scenario is out of the question. Lukashenka can end up either like Yanukovych or like Ceausescu—in exile (living off the fortune he stole) or shot in the same manner in which he killed his political opponents. His closest allies will face either the same fate, that, or international justice. RTWT