Encouraging the creation of a cadre of ‘active citizens’ in Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova will help increase social cohesion and build ‘cognitive resilience’ to malign Russian influence from the ground up, according to a new report from Chatham House, the London-based foreign policy think tank.

Encouraging the creation of a cadre of ‘active citizens’ in Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova will help increase social cohesion and build ‘cognitive resilience’ to malign Russian influence from the ground up, according to a new report from Chatham House, the London-based foreign policy think tank.

Building the resilience of societies and institutions offers a potentially viable strategy for the three countries to achieve more secure and less damaging cohabitation with Russia, analysts Mathieu Boulègue, Orysia Lutsevych and Anaïs Marin contend in Civil Society Under Russia’s Threat: Building Resilience in Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova, a report funded by the National Endowment for Democracy.

The Chatham House policy recommendations focus mostly on ‘soft’ elements of resilience, such as people and ideas, with the aim of building inclusion, promoting the circulation of information, and strengthening the leverage of Western assistance.

The EU’s eastern neighbours have plenty of internal challenges to resilience, according to a recent analysis. Some countries are extremely weak, oligarchy-dominated democracies (Moldova, Ukraine and Georgia) while others are outright authoritarian states with weak power transition mechanisms. Nevertheless, all of the eastern partners are still more resilient than the EU’s southern neighbours, note the authors of After the EU global strategy – Building resilience:

The EU’s eastern neighbours have plenty of internal challenges to resilience, according to a recent analysis. Some countries are extremely weak, oligarchy-dominated democracies (Moldova, Ukraine and Georgia) while others are outright authoritarian states with weak power transition mechanisms. Nevertheless, all of the eastern partners are still more resilient than the EU’s southern neighbours, note the authors of After the EU global strategy – Building resilience:

Even when facing significant challenges to resilience, the EU’s eastern neighbours have mostly been able to manage without descending into civil wars or resorting to large-scale violence. As a result, if left to their own devices they most probably would be in a position to muddle through without major war-related crises – unless broader geopolitical games come into play. Resilience is at its weakest when external and internal pressures converge to push states beyond breaking point. Ukraine is one such example: after the fall of Yanukovich in early 2014, the ensuing civic political conflict morphed into a civil war (with some interstate war characteristics) once Russia stepped in.

“While recognising the need to strengthen other aspects of resilience in the EU’s eastern neighbours (ranging from democracy to energy and economic resilience), the single most urgent task is to strengthen resilience vis-à-vis external actors meddling with internal security.”

The Chatham House authors summarize their findings:

The Chatham House authors summarize their findings:

- Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova, constituting the western rim of the EU’s Eastern Partnership group of countries, are at the front line of a heated battle for their own future. They are highly exposed to various threats emanating from Russia, which deploys a set of tools aimed at weakening their sovereignty.

- State cohesion and stability in Eastern Europe are key to wider European security. Building societal and institutional resilience to Russia’s negative influence in the three countries represents a potentially viable strategy for more secure and less damaging cohabitation with the current Russian regime.

- Civil society has an important role to play in building social cohesion, and in insulating the three countries against Russian influence. The ability to recognize Russian interference, design effective responses and prevent damaging trends from taking hold is key to strengthening country defences.

Ukraine

Ukraine can be viewed as a political ‘laboratory’ in which Russia has tested a variety of measures to exert influence, and at the same time as an example of resilience. Since 2014, many of the levers of Russian influence have weakened as a consequence of civil society mobilization associated with Ukraine’s ‘Revolution of Dignity’ and subsequent reforms.

Ukraine can be viewed as a political ‘laboratory’ in which Russia has tested a variety of measures to exert influence, and at the same time as an example of resilience. Since 2014, many of the levers of Russian influence have weakened as a consequence of civil society mobilization associated with Ukraine’s ‘Revolution of Dignity’ and subsequent reforms.- Vulnerabilities remain in Ukraine. These include high levels of insecurity stemming from the Russia-fuelled conflict in the Donbas region; a predatory and fractured political environment (the turbulence from which creates the risk of further internal destabilization); and weak information security alongside susceptibility to Russian disinformation.

- Strengthening and sustaining Ukraine’s resilience to Russian influence is a long-term project. Key opportunities for improvement exist in the wide popular support for Ukraine’s democratic identity; in an ongoing process of administrative decentralization, aimed at improving governance; and in the continued pursuit of measures by the state and civil society to mitigate vulnerabilities related to the conflict. High mobility across the line of contact, and citizens’ openness to some political compromise, offer ample opportunities to prepare the ground for future reintegration of parts of Donbas into Ukraine proper.

Belarus

Of all the Eastern Partnership countries, Belarus is by far the most vulnerable to Russian influence. This reflects its structural dependence on Russia in the economic, energy, geopolitical and socio-cultural spheres.

Of all the Eastern Partnership countries, Belarus is by far the most vulnerable to Russian influence. This reflects its structural dependence on Russia in the economic, energy, geopolitical and socio-cultural spheres.- Alongside structural dependence, Belarus displays other characteristics that allow Russia to have a strong impact on civil society. These include a weak national identity, issues around language, the pervasiveness of Russian information in the media, exposure to Russian information warfare, and the presence in Belarus of Russian government-organized NGOs (GONGOs) and the Russian Orthodox Church.

- Opportunities to strengthen Belarus’s resilience at the level of civil society include what can be termed ‘soft Belarusianization’. This self-organized movement seeks to promote national characteristics, using affirmative action in support of Belarusian culture and language. However, civil society activity and the actors involved remain vulnerable to arbitrary repression by the regime.

Moldova

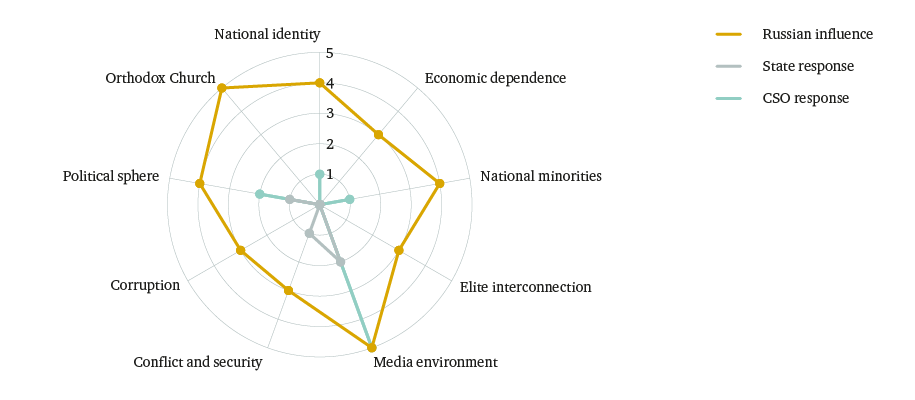

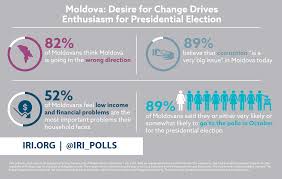

In Moldova, the vulnerabilities exploited by Russia to exert negative influence are generally well known. Strong linkages between politics, the media and the Moldovan Orthodox Church render Moldovans a captive audience for Russia’s propaganda. Moldovans’ already low trust in institutions is being further undermined, creating a legitimacy crisis for the state.

In Moldova, the vulnerabilities exploited by Russia to exert negative influence are generally well known. Strong linkages between politics, the media and the Moldovan Orthodox Church render Moldovans a captive audience for Russia’s propaganda. Moldovans’ already low trust in institutions is being further undermined, creating a legitimacy crisis for the state.- In Moldova, there is a large discrepancy between the level of response from civil society organizations (CSOs) and the more limited efforts of the authorities to address vulnerabilities to Russian influence and propaganda.

- Opportunities to strengthen resilience are limited, but some exist around information campaigns, and measures to promote education and civic awareness. This could help to build what we can term ‘cognitive resilience’ – broadly, developing citizens’ critical thinking, especially in terms of building awareness about Russian disinformation – using the Western-based diaspora as a spearhead for change.

Among specific policy gaps, there is a need for more inclusive state-building; media reform (including capacity-building for independent media); civil society support; and the linking of financial and technical assistance to tangible progress in policy reforms via ‘smart conditionality’. RTWT