RFE/RL

In his July 23 address at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared that 50 years of engaging China had failed, denounced Chinese leader Xi Jinping as a “true believer in a bankrupt, totalitarian ideology,” and warned Americans that “Communist China is already within our borders.” In comments yesterday, he lauded Australia’s government for “standing up for democratic values and the rule of law, despite intense, continued, coercive pressure from the Chinese Communist Party to bow to Beijing’s wishes.”

Insisting that “we must induce China to change”—or else “Communist China will surely change us,” Pompeo called for an “alliance of democracies” to curtail Beijing’s aggression.

The proposal is necessary and problematic, argues Mira Rapp-Hooper, the Stephen A. Schwarzman Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of “Shields of the Republic: The Triumph and Peril of America’s Alliances.” With each year, the United States will be less able to stand up to China alone. Its allies in Europe and Asia, however, will remain capable and steady — exactly the sorts of partners the United States should want as it faces China’s rise or confronts global health emergencies and climate change.

The proposal is necessary and problematic, argues Mira Rapp-Hooper, the Stephen A. Schwarzman Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of “Shields of the Republic: The Triumph and Peril of America’s Alliances.” With each year, the United States will be less able to stand up to China alone. Its allies in Europe and Asia, however, will remain capable and steady — exactly the sorts of partners the United States should want as it faces China’s rise or confronts global health emergencies and climate change.

Washington should not hesitate to stand up for its values and call out Beijing for its indefensible human rights violations and trade practices, according to Council on Foreign Relations analyst Philip H. Gordon, the author of the forthcoming Losing the Long Game: the False Promise of Regime Change in the Middle East, and James Steinberg, a professor at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs.

But Americans should also have more confidence in their own ability to resist Chinese propaganda and outcompete Beijing, they write for Foreign Policy. Rebuilding the United States’ domestic strength and unity—and leveraging rather than alienating democratic allies—would be a more effective approach than wishful thinking that rhetorical assaults from top U.S. officials will magically transform the Chinese regime.

But is the European Union doing enough to meet China’s authoritarian influence with democratic resilience? asks Visegrad Insight.

In April, the EU’s foreign-policy arm drafted a report on disinformation that implicated China. Beijing pressed for the report to be watered down after part was leaked, according to an internal EU communication, The Wall Street Journal reports:

In April, the EU’s foreign-policy arm drafted a report on disinformation that implicated China. Beijing pressed for the report to be watered down after part was leaked, according to an internal EU communication, The Wall Street Journal reports:

Ensuing outcry over possible EU self-censorship prompted Brussels to stiffen its position. Last month, the bloc released a plan to counter disinformation that for the first time explicitly named China, marking a significant shift. …Disputes surrounding the April disinformation report bared Europe’s competing views on China. Some see it as a threat to democracy needing resolute opposition.

“We insist on playing chess with them while they are boxing,” said Jakub Kalensky, who used to work on the EU’s East Stratcom Task Force countering disinformation and is now at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Other analysts have a different take on the nature of China’s global ambitions.

Despite vociferous claims to the contrary, Beijing and Moscow are not engaged in a multi-dimensional plot to undermine the global order, argues one observer. Such scapegoating diverts attention, often purposely, from repeated Western failures of commission and omission. Chinese and Russian actions have at times been disruptive and destabilising. But they scarcely amount to a conscious or coordinated strategy to build a new, authoritarian world, according to analyst Bobo Lo.

No country has benefited more than China from the post-Cold War order, he adds. At the same time, it thinks and acts like a traditional great power, Lo writes for the Lowy Institute:

No country has benefited more than China from the post-Cold War order, he adds. At the same time, it thinks and acts like a traditional great power, Lo writes for the Lowy Institute:

Its commitment to global order is entirely self-interested, pronouncements about ‘win–win’ outcomes notwithstanding. Its engagement is also conditional on maintaining privileged conditions. The ideal order is one that supports the legitimacy of Party rule, facilitates China’s continued economic growth (through global free trade), and helps the Party to keep out ‘harmful’ foreign influences, such as liberal ideas of democracy, rule of law, and human rights.

Chinese agents hacked computer networks (The Times reports (HT:CFR), belonging to the Vatican and the Holy See’s Study Mission to China beginning in early May, according to a U.S. cybersecurity firm.

In any case, the U.S. administration’s target appears to be shifting from China to the Communist Party, notes one observer – and with good reason.

“The Chinese Communist Party’s instructions are the most essential feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics.” That was the front-page headline of the People’s Daily newspaper, the main mouthpiece of the party recently, quoting President Xi Jinping’s article for the latest edition of Qiushi, a journal of party theory.

National Endowment for Democracy

Xi called for a further concentration of power: “The party will instruct everything” from politics and the military to the civilian and academic sectors. “Our party must mature even further and become stronger, and step up our combat power.”

Disappeared for calling Xi a “clown,” Chinese property tycoon Ren Ziqiang has been kicked out of the Communist Party and now faces a criminal investigation that could end with prosecution. “If this is not political persecution, then what is?” a friend of Ren’s, a Chinese businesswoman, told VOA Mandarin:

Cai Xia, a former professor at China’s Central Party School who is believed to have left China recently for the U.S., wrote an article in support of Ren, saying “Persecuting Ren Zhiqiang and cruelly suppressing different opinions within the party is another evil crime committed by the Xi gangster.”

The principle of absolute party control of the military is one of the pillars of China’s governance model. It follows the central rule—“The party commands the gun, and the gun must never be allowed to command the party”—coined by Mao Zedong, he writes for the Africa Center for Strategic Studies:

As China deepens its ties to African militaries, including through training and education initiatives, Beijing brings its perspective on party-army relations. The venues through which it does this have been growing steadily in the past decade. For example, under its China-Africa Action Plan 2018-2021, China receives 60,000 African students annually, which surpasses both the United States and United Kingdom. China provides an additional 50,000 professional training opportunities and 50,000 government fellowships to African public servants. Around 5,000 slots go to military professionals, up from 2,000 under its 2015-2018 Plan.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

Most African constitutions and military professionalism advocates argue that professional African militaries can only be established via apolitical armed forces that are committed to serve the nation rather than a single political party, Nantulya adds. Regardless, the foundations for China’s ideological push to advance its party-army model in Africa have been laid.

Political ambitions make China’s emissions growth inevitable even as the economy falters, analyst Richard Smith writes for Foreign Policy in The Chinese Communist Party Is An Environmental Catastrophe.

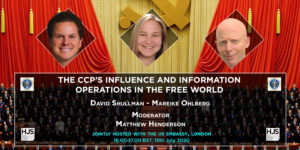

China is increasingly a matter of debate in EU institutions. After cases of political filtering and self-censorship, the Union appears set to take a more defensive approach against its authoritarian competitor, Visegrad Insight adds.

This was the topic of a Visegrad Insight Transatlantic breakfast discussion (below), which took place on 21 July 2020.

Speakers at the meeting:

- Miriam Lexmann, Member of the European Parliament from Slovakia

- Monika Richter, Senior Director at CounterAction

- Peter Kreko, Director at Hungarian Think Tank Political Capital, Europe’s Futures Fellow at IMW/ERSTE Foundation

The discussion was moderated by Wojciech Przybylski, Editor-in-Chief at Visegrad Insight.

Peter Kreko, drawing upon a project of monitoring MEP’s activities, conducted in partnership with the National Endowment for Democracy and Visegrad Insight among others, stressed that the EP does the most to counter malign influence from the authoritarian regimes. There is an important shift recently, as China appears more in the discussions in the European Parliament. Importantly, the rising topic regarding China appears to be human rights violations, rather than trade and investment deals.

Recent Visegrad Insight publications on the topic:

- An assessment of the global crisis of trust and disinformation

- An interview with Christopher Walker, VP for Studies and Analysis at NED, about sharp power and how it limits our democratic public space

Visegrad Insight

“If we have evidence, we should not shy away from naming and shaming,”

“If we have evidence, we should not shy away from naming and shaming,”  China is energetically promoting its party-army model, whereby the army is subordinate to a single ruling party, a framework antithetical to Africa’s multiparty democratic systems with an apolitical military accountable to elected leaders, says analyst

China is energetically promoting its party-army model, whereby the army is subordinate to a single ruling party, a framework antithetical to Africa’s multiparty democratic systems with an apolitical military accountable to elected leaders, says analyst