Does the deepening of cracks in America’s political system actually boost the legitimacy of China and other authoritarian regimes? a prominent analyst asks.

Does the deepening of cracks in America’s political system actually boost the legitimacy of China and other authoritarian regimes? a prominent analyst asks.

The fact is that damage to America’s reputation doesn’t actually bolster the reputation of authoritarian states. There is no direct connection between the two, argues Maria Repnikova, a 2020-21 fellow at the Wilson Center, assistant professor of global communication at Georgia State University and the author of “Media Politics in China: Improvising Power Under Authoritarianism.”

Drawing on her research about political communication in authoritarian countries, especially China, she sees no reason to believe that even this hard a hit to America’s prestige will burnish the image of authoritarians elsewhere, she writes in the Times:

The storming of the U.S. Capitol and the dramatic political fallout from that isn’t a gift for authoritarian leaders bent on denouncing America’s shortcomings so much as an opportunity for America to rebuild itself and its image worldwide. It is how America itself handles this crisis in the weeks and months ahead that will determine how this story, and America at large, ultimately is perceived by people in China, Russia and beyond.

The Chaos in America Is No Gift to Autocrats https://t.co/sm5LWAPK2X

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) January 15, 2021

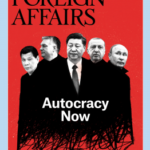

Autocrats around the world reveled in the mayhem that broke out in the U.S. Capitol on January 6. On closer inspection, however, authoritarians have little to celebrate, argues Daniel Twining, President of the International Republican Institute, a core institute of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). The events of Jan. 6 prove that democracy is not a cure-all, but its institutions are a bulwark against mob rule, civil war, and tyranny, he writes in Foreign Affairs.

The new Biden Administration must make democracy and human rights support a central component of a new American foreign policy. This can be done through strong rhetoric, personnel decisions, and global engagement, argues Nicole Bibbins Sedaca, the Kelly and David Pfeil Fellow at the George W. Bush Institute:

The new Biden Administration must make democracy and human rights support a central component of a new American foreign policy. This can be done through strong rhetoric, personnel decisions, and global engagement, argues Nicole Bibbins Sedaca, the Kelly and David Pfeil Fellow at the George W. Bush Institute:

- The president’s early speeches should reaffirm strong U.S. leadership in support of democracy and human rights globally, a commitment to bipartisanship and democracy at home, and a linkage between democracy and American security and prosperity. The new administration should shine a light on the plight of those suffering significant human rights abuses, from the Uighurs in China to the Rohingya forcibly displaced from Burma to the citizens of North Korea.

- The new president should appoint or nominate senior staff within the White House, the State Department, the Defense Department, and U.S. Agency for International Development who will integrate democracy and human rights support into our broader national security, foreign policy, and development efforts.

- Likewise, he should direct our security agencies to integrate democracy and protection of human rights into our national security planning and rhetoric.

- His budget requests and programming should also reflect the centrality of democracy and human rights support in our foreign policy and aid decisions.

- Finally, he should meet early in his administration with key democratic allies, including those from NATO, the European Union, Japan, and South Korea, as well as emerging democracies from each region, to reiterate the centrality of democracy in America’s global engagement and urge collaborative efforts to jointly strengthen global democracy and protect human rights.

National security institutions must better understand and tackle our crisis of democracy and the underlying economic, racial, and cultural grievances that fuel it, adds Jon Bateman, a fellow in the Cyber Policy Initiative of the Technology and International Affairs Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. And the U.S. government should harness its many experts on global democracy promotion, de-radicalization, and economic development—redeploying a portion of them to the home front, he contends.