The pattern is familiar to historians, a rising power challenging an established one, with a familiar complication: For decades, the United States encouraged and aided China’s rise, working with its leaders and its people to build the most important economic partnership in the world, one that has lifted both nations, writes Philip P. Pan, The New York Times’s Asia Editor:

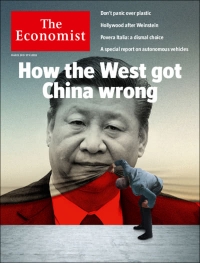

During this time, eight American presidents assumed, or hoped, that China would eventually bend to what were considered the established rules of modernization: Prosperity would fuel popular demands for political freedom and bring China into the fold of democratic nations. Or the Chinese economy would falter under the weight of authoritarian rule and bureaucratic rot.

“But neither happened. Instead, China’s Communist leaders have defied expectations again and again,” Pan observes.

China’s Communists studied and obsessed over the fate of their old ideological allies in Moscow, determined to learn from their mistakes. They drew two lessons: The party needed to embrace “reform” to survive — but “reform” must never include democratization, adds Pan, the author of “Out of Mao’s Shadow: The Struggle for the Soul of a New China”:

China’s Communists studied and obsessed over the fate of their old ideological allies in Moscow, determined to learn from their mistakes. They drew two lessons: The party needed to embrace “reform” to survive — but “reform” must never include democratization, adds Pan, the author of “Out of Mao’s Shadow: The Struggle for the Soul of a New China”:

The pro-democracy movement in 1989 was the closest the party ever came to political liberalization after Mao’s death, and the crackdown that followed was the furthest it went in the other direction, toward repression and control. After the massacre, the economy stalled and retrenchment seemed certain. Yet three years later, Deng used a tour of southern China to wrestle the party back to “reform and opening up” once more.

China’s Communist leaders didn’t like the West’s playbook. So they wrote their own, Pan suggests.

Xi Jinping’s ruling Communist party adopted a series of pseudo-democratic measures, which helped smooth out the rough edges of autocratic rule, he notes:

The party introduced term limits and mandatory retirement ages, for example, making it easier to flush out incompetent officials. And it revamped the internal report cards it used to evaluate local leaders for promotions and bonuses, focusing them almost exclusively on concrete economic targets.

The party introduced term limits and mandatory retirement ages, for example, making it easier to flush out incompetent officials. And it revamped the internal report cards it used to evaluate local leaders for promotions and bonuses, focusing them almost exclusively on concrete economic targets.

These seemingly minor adjustments had an outsize impact, injecting a dose of accountability — and competition — into the political system, said Yuen Yuen Ang, a political scientist at the University of Michigan. “China created a unique hybrid,” she said, “an autocracy with democratic characteristics.”

“In effect, Mr. Xi seems to believe that China has been so successful that the party can return to a more conventional authoritarian posture — and that to survive and surpass the United States it must,” Pan concludes. “China is not the only country that has squared the demands of authoritarian rule with the needs of free markets. But it has done so for longer, at greater scale and with more convincing results than any other.” RTWT