\

Venezuela’s parliamentary elections, scheduled for 6 December, will renew its National Assembly for a five-year term. But since 2015, the regime has become less evenhanded when it comes to elections, according to a new report from the Andrés Bello Catholic University (UCAB) and International IDEA. It raises concerns over such unacceptable practices as vote buying, “assisted voting”, fostering voter abstention by kindling doubts as to whether votes really count, the disqualification of opposition parties and candidates, court-ordered takeovers of the main opposition parties, the co-opting of minority opposition parties, and patronage in elections, are all on the rise.

Several of these practices are in place today, leading to an a priori rejection of the upcoming parliamentary elections not only by the opposition political parties that have decided not to take part, but also by most voters and a significant portion of the democratic international community, adds the report, which provide a diagnosis and conclusions on the election, as well as to formulate recommendations on key aspects of electoral integrity

OHCHR

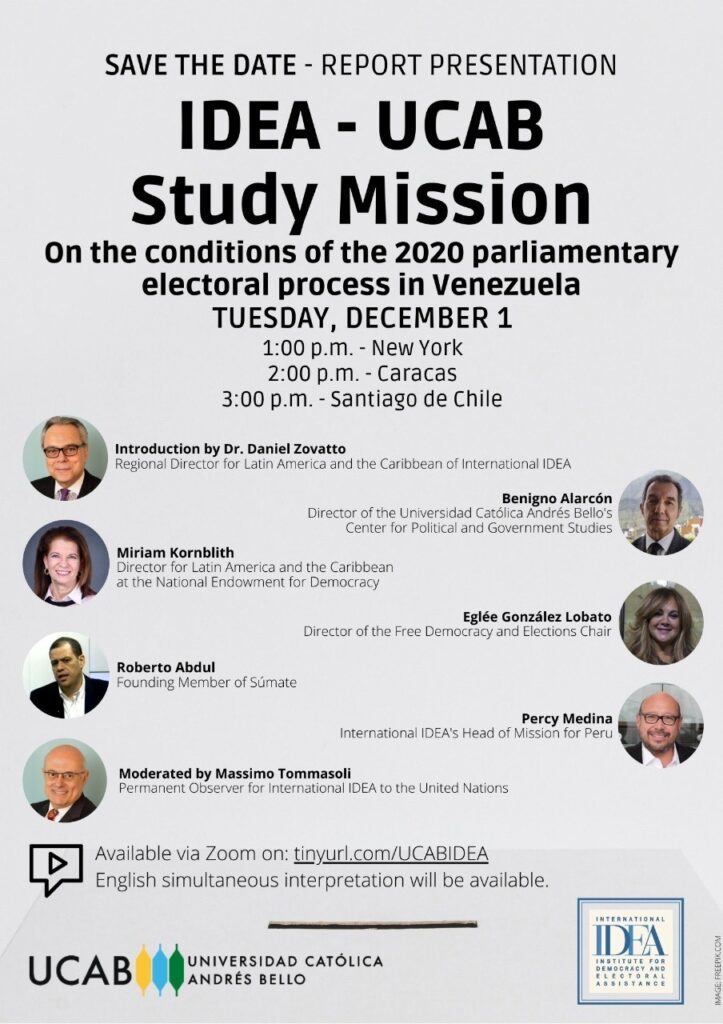

You can access the full report here. Miriam Kornblith, Senior Director for Latin America and the Caribbean at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), participated in a discussion of the report (above).

The vast majority of Venezuelans will not vote this Sunday. And how could they? Jorge Jraissati, president of the Venezuelan Alliance, notes in the National Review. The Maduro regime has 1) banned most opposition candidates from running, 2) imprisoned prominent opposition leaders such as Leopoldo Lopez, 3) coerced and intimidated citizens into voting for the socialist party, 4) engaged in verifiable manipulation of vote tallies, 5) organized the process through an election authority controlled by members of Maduro’s party, 6) murdered protesters who exercised their right to assemble peaceably, and 7) disallowed international organizations from observing the vote — among other violations of the political rights of Venezuelans.

Although the result is preordained, the vote will matter. The regime’s takeover of the National Assembly will be a big step in its march towards full dictatorship, The Economist reports. It will strip Juan Guaidó of his job as the legislature’s president. As the holder of that office he claims to be Venezuela’s rightful president, on the grounds that Mr Maduro won re-election fraudulently in 2018, it adds:

The opposition’s current hold on the legislature came about by accident. In 2015 Venezuela’s “Bolivarian” regime, in power for 16 years, was so convinced that it would win the election held that year it did not cheat enough to secure victory. It lost in a landslide, especially in the poor barrios that were once its stronghold. Venezuelans rightly blamed Mr Maduro for a severe recession (which was about to get much worse), high inflation (soon to become hyperinflation) and shortages of basic goods.

Consolidating dictatorship – Venezuela’s regime will win the legislative election, by a lot https://t.co/cxvdS5Vu8B

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) December 2, 2020

Back in December 2018, the regime was as despised as today, but unchallenged. Politics were off the radar. Most people didn’t even know elections were about to go down, a nation more focused on day-to-day survival. Then came January 2019, with its surprising, sudden influx of political optimism, another kind of mirage but this time about the promise of change around half of the world saying that Juan Guaidó was the legitimate president, adds Caracas Chronicles:

That didn’t last. After the failed humanitarian operation in February and the Guri dam crisis in March took us back to reality, Maduro had to restart the confection of a sense of normality from square one, while Venezuelans had to learn how to deal with an even harder life, with heavy shortages of power and fuel.

The upcoming election will aggravate the crisis in Venezuela, said Father Francisco José Virtuoso, Dean of the Andres Bello Catholic University, noting that recent electoral processes in Chile, Bolivia and the United States served to highlight “very serious” political crises and “terribly polarized” societies with elements of strong political confrontation.

The upcoming election will aggravate the crisis in Venezuela, said Father Francisco José Virtuoso, Dean of the Andres Bello Catholic University, noting that recent electoral processes in Chile, Bolivia and the United States served to highlight “very serious” political crises and “terribly polarized” societies with elements of strong political confrontation.

It is not possible to generate confidence in an election, “if underlying issues are not addressed”, such as the formation of the current National Electoral Council (CNE), untimely changes in electoral regulations, doubts about the new voting system, and the judicialization and intervention of political parties, said Daniel Zovatto, International IDEA’s Regional Director for Latin America and the Caribbean.

In Venezuela’s case, we can see mechanisms of competitive patronage, added Benigno Alarcón, Director of the Center for Political and Government Studies of the Andrés Bello Catholic University (CEPyG-UCAB). Authoritarian regimes “repeatedly face electoral processes against a fragmented opposition, a situation that is not directly related to electoral conditions, but to the political game.”