The #coronavirus pandemic makes it a lot easier for strongman leaders to justify their blatant attacks on democracy. @joshuakeating for @Slate https://t.co/YXxUmtiIkh

— Freedom House (@freedomhouse) May 12, 2020

While other autocratic leaders used COVID-19 to grab more power and boost their image at home, Putin did exactly the opposite. Why so? asks analyst Polina Beliakova.

The coronavirus crisis demonstrates that the Kremlin seems to have reached its capacity of power. Indeed, attempts to grab more power would likely undermine Moscow’s authority. While supposedly employed as a face-saving measure, this behavior suggests that Putin has reached the limits of his power at home — and he knows it, she writes for War on the Rocks.

Henry Jackson Society

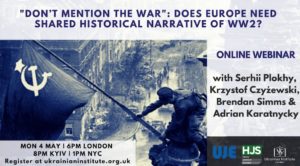

The Kremlin clings to the Stalinist interpretation of history for one primary reason: the truth of Eastern and Central Europe’s postwar history is an existential threat to the Putin regime, CEPA’s Krystyna Sikora contends (HT:FDD). Putin understands that only if the Kremlin continues to deny its own horrors of World War II can Russia accept Putinism, a regime so similar to the country’s authoritarian Soviet past. Only with acceptance, can Russia make strides towards democracy.

Democratic countries have a decidedly mixed record in handling the novel coronavirus pandemic, but the record among authoritarian regimes such as Alexander Lukashenko’s Belarus and Putin’s Russia has been almost universally bad, her CEPA colleague Brian Whitmore adds. This is clear to anybody paying attention. It would have taken more than a military parade to hide it.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

Last month, UN Watch, a Geneva-based human rights group, released a report on the upcoming election to the United Nations Human Rights Council. According to the group, governments seeking a place on the top human rights watchdog at the General Assembly session in October will include some of the world’s worst human rights abusers — among them Cuba, Saudi Arabia and Vladimir Putin’s Russia, Vladimir Kara-Murza (above, second left) writes for the Washington Post:

Russia’s candidacy did not come as a surprise. The government in Moscow has long been eager to return to the forum, from which it was dropped nearly four years ago. In February, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov used a speech in front of the council to excoriate Western democracies for “meddling in the domestic affairs of sovereign states” and imposing “highly dubious ‘values’ . . . unilaterally invented by the West.” Distinctly Soviet in style, Lavrov’s address included accusations of human rights abuses directed at Russia’s democratic neighbors, including the Baltic states.

Russia’s candidacy did not come as a surprise. The government in Moscow has long been eager to return to the forum, from which it was dropped nearly four years ago. In February, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov used a speech in front of the council to excoriate Western democracies for “meddling in the domestic affairs of sovereign states” and imposing “highly dubious ‘values’ . . . unilaterally invented by the West.” Distinctly Soviet in style, Lavrov’s address included accusations of human rights abuses directed at Russia’s democratic neighbors, including the Baltic states.

“When the U.N. . . . ends up electing human rights violators to the Human Rights Council, it indulges the very of culture of impunity it is supposed to combat,” said former Canadian Attorney General Irwin Cotler of the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights (RWCHR).