China is “fed up” with hearing complaints from the United States about its Belt and Road program to re-create the old Silk Road, Reuters reports. The regime is bridling at criticism that the ruling Communist Party uses BRI for the projection of its sharp power rather than to promote sustainable development.

Autocratic regimes like China’s are using their financial muscle to advance their geo-political agenda, analysts suggest. Since the global financial crisis, we have seen the rise of large bilateral bailouts by emerging powers eager to use “sharp power” to promote their economic and/or geopolitical interests, notes FT analyst Timothy Ash:

In particular, three big, new, bilateral providers of “sharp power lending” (SPL) have emerged as alternatives to the IMF, in the form of China, Saudi Arabia/UAE and Russia. The use of sharp power by these new emerging powers (or resurrected powers, in the case of Russia) has typically been as an alternative to IMF programmes, although it has also been used in conjunction with IMF programmes.

FPRI

China’s “united front” influence operations throughout the world are the focus of a special theme issue of China Brief.

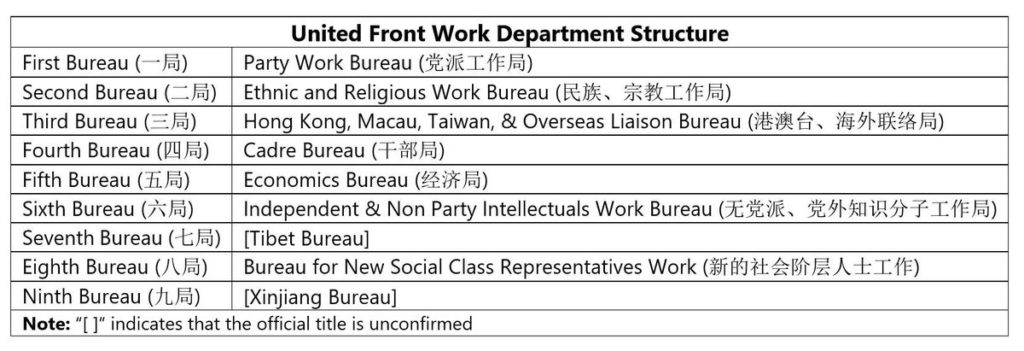

The Communist Party’s United Front Work Department (UFWD) handles a broad range of policy portfolios ranging from ethnic and religious affairs within China to seeking influence over ethnic Chinese communities and governments in foreign countries. However, in a much broader sense, the “united front” also represents a series of political strategies and tactics, employed by a variety of Chinese state-affiliated organizations, to pursue the interests of the Chinese Communist Party throughout the world, writes China Brief editor John Dotson.

Outside commentators frequently use the terms “foreign interference” or “foreign influence” to describe CCP-directed efforts to impact politics in other countries, prompting debates as to which term is best used when raising alarm bells about this phenomenon, notes analyst Anne-Marie Brady. Sometimes “political warfare” is also used to describe such activities (The Strategist, June 5, 2018). Military and strategic analysts tend to use the term “gray zone strategies” (The National Interest, May 2, 2017), she writes for China Brief:

Outside commentators frequently use the terms “foreign interference” or “foreign influence” to describe CCP-directed efforts to impact politics in other countries, prompting debates as to which term is best used when raising alarm bells about this phenomenon, notes analyst Anne-Marie Brady. Sometimes “political warfare” is also used to describe such activities (The Strategist, June 5, 2018). Military and strategic analysts tend to use the term “gray zone strategies” (The National Interest, May 2, 2017), she writes for China Brief:

Some writers, including many CCP-affiliated ones, try to use the characterization of “soft power” to describe the CCP’s activities (The Wilson Center, September 18, 2017); however, Joseph Nye, who invented the soft power concept, rejects the PRC (and Russian) arrogation of his terminology (Foreign Policy, April 29, 2013). The U.S. National Endowment for Democracy has coined the phrase “sharp power” to describe the influence activities of authoritarian governments, while Russian scholars prefer “smart power” (International Forum for Democratic Studies, December 6, 2017)…Whatever the term applied by outside observers, the term used by the CCP itself to describe such phenomena is “united front work”…RTWT

Some writers, including many CCP-affiliated ones, try to use the characterization of “soft power” to describe the CCP’s activities (The Wilson Center, September 18, 2017); however, Joseph Nye, who invented the soft power concept, rejects the PRC (and Russian) arrogation of his terminology (Foreign Policy, April 29, 2013). The U.S. National Endowment for Democracy has coined the phrase “sharp power” to describe the influence activities of authoritarian governments, while Russian scholars prefer “smart power” (International Forum for Democratic Studies, December 6, 2017)…Whatever the term applied by outside observers, the term used by the CCP itself to describe such phenomena is “united front work”…RTWT

Europe has started re-evaluating its policies with respect to the China challenge, said Philippe Le Corre, nonresident senior fellow in the Europe and Asia Programs at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Europe remains divided, with a number of countries at its periphery benefiting from Chinese economic assistance. Still, the European Union is now standing as one of the strongest advocates of liberal and democratic values in the world, many of them shared on this side of the Atlantic, he told the House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee, Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, Energy, and the Environment (above).

Jamestown China Brief