Hungary’s illiberal premier Viktor Orban has rewritten Hungary’s constitution and dismantled judicial checks on power, stifled a once vibrant media, forced a top university out of the country, and criminalized the activities of some human rights organizations. Meanwhile, he has won deeply flawed elections by vilifying migrants, Muslim “invaders” and the Jewish “financiers” that supposedly support them, according to Rob Berschinski, the senior vice president for policy at Human Rights First, and Hal Brands, the Henry Kissinger distinguished professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

Hungary’s illiberal premier Viktor Orban has rewritten Hungary’s constitution and dismantled judicial checks on power, stifled a once vibrant media, forced a top university out of the country, and criminalized the activities of some human rights organizations. Meanwhile, he has won deeply flawed elections by vilifying migrants, Muslim “invaders” and the Jewish “financiers” that supposedly support them, according to Rob Berschinski, the senior vice president for policy at Human Rights First, and Hal Brands, the Henry Kissinger distinguished professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

While anti-democratic, pro-Russian behavior undertaken by a NATO ally raises several immediate security-related challenges, the full scope of the danger presented by Orbanism is even greater. That threat comes from how the Hungarian leader is revising the darker chapters in European history to benefit his party’s hold on power, they write for The Washington Post.

Troubling irredentism

“Orban’s ongoing efforts to rewrite Hungary’s role in the Holocaust are as well-documented as they are troubling,” they add. “Less well understood, however, are the actions and rhetoric he employs in support of Hungary’s claims to territory lost after World War I.”

EU leaders attending an informal summit in Romania on May 9 adopted a statement outlining commitments to reform in various areas and pledging to defend democracy and the rule of law, RFERL reports:

EU leaders attending an informal summit in Romania on May 9 adopted a statement outlining commitments to reform in various areas and pledging to defend democracy and the rule of law, RFERL reports:

The summit takes place just two weeks before European Parliament elections that could usher in a new wave of populist and euroskeptic parties who could have a growing influence on the bloc’s decision-making. The meeting adopted the Sibiu Declaration — a 10-point statement outlining commitments to reform in various areas, which was dubbed by some Brussels diplomats as the “10 Commandments” for the next EU Commission.

“We will continue to protect our way of life, democracy, and the rule of law,” the statement says.

Illiberal democracy is the euphemism Orban uses to describe the state he is building, Franklin Foer writes for The Atlantic.

Illiberal democracy is the euphemism Orban uses to describe the state he is building, Franklin Foer writes for The Atlantic.

What is specific to populists like Orban and Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is the claim that they are the only ones who represent those they often call “the real people.” The implication is not only that all other contenders for power are corrupt or lack legitimacy, but also that citizens who fail to support populists do not truly belong to the people at all, notes Jan-Werner Müller, a professor of politics at Princeton University and the author of “What is Populism?”

If, by this logic, only the populists represent the silent majority, then by definition, they will always win elections, as long as the majority is allowed to speak, he writes for The New York Times:

If, by this logic, only the populists represent the silent majority, then by definition, they will always win elections, as long as the majority is allowed to speak, he writes for The New York Times:

When populists do not succeed at the polls, it is imperative for them to offer an explanation that cannot just come down to what other politicians would normally say: namely that they are right, their opponents are wrong, and they will try harder next time to convince citizens. Instead, populists often suggest in a more or less veiled manner that they are dealing with not a silent but a silenced majority. Someone, they insinuate, must have been manipulating matters behind the scenes to prevent the people from electing their only genuine representatives — hence the connection between populism and allegations of voter fraud (which are themselves fraudulent) as well as broader conspiracy theories.

The looming question is whether far-right leaders across Europe will capitalize on the Spanish elections to put their stamp on continent-wide policies, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and National Endowment for Democracy board member] Anne Applebaum tells PRI.

In many European countries where there are several parties in parliament, preventing an angry minority from dominating a fragmented majority is an important strategic objective, she writes for The Washington Post :

But that’s a political strategy. As I’ve written in the past, some centrist parties are also working on an intellectual strategy, designed to prevent the far-right from monopolizing the language of patriotism. This has been President Emmanuel Macron’s tactic in France; he has sought to redefine “patriotism” as a term that implies respect for democracy and the rule of law, not just ethnic nationalism. The Swiss campaign group Operation Libero has also sought to remind people of Switzerland’s liberal traditions in an effort to push back against a populist narrative that defines Swiss “tradition” more narrowly.

It’s important to try to understand the common methods of these new parties, adds Carl Bildt,They use social media to great effect to polarize and provoke. They frequently disseminate a diverse range of conspiracy theories and blatantly false claims by networks that form the fringe of the fringe. And they constantly play on fear — whether that is fear of Muslims, immigration, feminism or the disintegration of the nation,

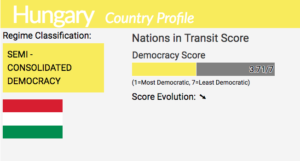

What is a progressive foreign policy approach toward backsliding liberal democracies? asks Daniel W. Drezner, a professor of international politics at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and a regular contributor to PostEverything. Progressives are skeptical about converting oligarchies into democracies. How do they feel about democracies trending in a negative direction, however? What about Hungary? Brazil? Poland? Turkey? If progressives want U.S. allies to share liberal values, what is the response when these countries trend in an illiberal direction?