Screengrab

Next month’s virtual Summit for Democracy will take place against a “gloomy backdrop,” The New Yorker’s Sue Halpern writes. When President Joe Biden announced the summit, back in August, the goal seemed to be to reëstablish America’s standing in the world by championing human rights and democratic practices.

“Democracy doesn’t happen by accident,” Biden said in February. “We have to defend it, fight for it, strengthen it, renew it.”

But this month, for the first time, the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance added the United States to its list of “backsliding” democracies, she observes.

Does the summit risk flattering the enemy?

Even now, after eye-catching lapses and reversals (the US, Turkey), a far larger share of humanity lives under democratic rule than did in 1975. All of which is to say: don’t do the strongmen’s propaganda work for them, adds FT analyst Janan Ganesh. Autocracy tends to live on a sense of historic inevitability as the coming force. An out-of-the-ordinary gathering of free nations, with its air of siege, might inadvertently lend a bogus credence to that idea.

China is working to strengthen relations with countries not invited to the summit, apparently concerned that the virtual meeting will lead to Taiwan’s recognition by the international community. Foreign Minister Wang Yi held a meeting with Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian of Iran, another country not invited to the democracy summit, Nikkei reports.

China is working to strengthen relations with countries not invited to the summit, apparently concerned that the virtual meeting will lead to Taiwan’s recognition by the international community. Foreign Minister Wang Yi held a meeting with Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian of Iran, another country not invited to the democracy summit, Nikkei reports.

One of China’s leading ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomats, Wang said that the aim of the summit “is, in essence, to instigate division in the world under the banner of democracy, incite bloc confrontation with ideological lines, and attempt to carry out American-style transformation of other sovereign countries to serve the strategic needs of the United States itself,” the Chinese summary said.

Leading Russian and Chinese diplomats continued an ideological offensive against the summit with a joint article in the Washington-based National Interest. The December 9-10 event would “stoke up ideological confrontation and a rift in the world, creating new ‘dividing lines,” ambassadors Anatoly Antonov of Russia and Qin Gang of China wrote, describing the US plan as “an evident product of its Cold-War mentality.”

Democracy “can be realized in multiple ways, and no model can fit all countries,” they added. “No country has the right to judge the world’s vast and varied political landscape by a single yardstick.”

CEPA

But Russia and China’s hostility to the summit is more revealing than they intend, confirming that “unelected despots have cause to worry,” says a leading analyst.

The Russian and Chinese ambassador’s article denouncing the summit claims that a “global polycentric architecture” is inexorably taking shape and the summit “could strain the objective process,” whatever that means, notes former Economist editor Edward Lucas. Jargon cloaks illogicality. If the triumph of the new order is really unavoidable, why complain about futile attempts to resist it?

Cultivating democratic resilience

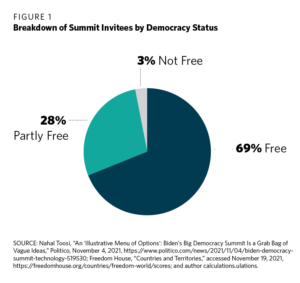

The actual event may be little more than an elaborate Zoom call. The guest list is open to criticism (Bosnia, Hungary, and Singapore are not invited, but Pakistan, Iraq, and the Democratic Republic of Congo are). But it has already brought results, adds Lucas, an analyst with the Center for European Analysis, and a contributor to the National Endowment for Democracy’s sharp power project (right).

Does the summit signal the start of a new international order? The South China Morning Post asks. “It is commendable for democracies to stand up to authoritarianism, but it remains far too early to tell if this summit could be any different from other international gatherings that are high on pomp and ceremony and low on substance,” it states.

The framing of the initiative as a Summit for Democracy rather than a Summit of Democracies indicates a focus on fostering democratic renewal, rather than forming an alliance against external enemies, says DIIS senior researcher Rasmus Sinding Søndergaard. This is promising for three reasons, he suggests:

- First, and most importantly, while China, Russia and other authoritarian regimes are seeking to undermine democracy, the democratic backsliding of most countries in recent years mainly has internal causes. The Summit should reflect this fact by exploring ways in which democracies can counter authoritarian interference without losing sight of the main challenge of fixing their intrinsic problems.

- Second, framing the Summit as part of an ideological competition between democracy and autocracy risks alienating key democratic allies, including several European countries that are uncomfortable with this rhetoric.

- Third, such a framing risks generating a backlash from authoritarians, who could exploit the Summit to strengthen cooperation among themselves. Both China and Russia have already derided the Summit as an ideological crusade.

Credit: CIMA

Will the summit do anything to stop the alarming trend of democratic backsliding around the world? asks Jeanne Bourgault, president and CEO of Internews, a nonprofit that supports independent media in 100 countries. The event holds the potential to bolster the journalists, filmmakers, artists and activists who draw attention to issues that matter, help citizens make informed decisions, and hold power to account. But we must meet this moment with action, policy change, and money — not just words, she writes for The Hill.

Identifying the participants for such a major diplomatic gathering is a complicated process, and settling on the final summit list was more a product of bureaucratic and interagency sausage making than anything more sublime, adds Steven Feldstein, a senior fellow in Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program. What considerations were at play?

The Biden administration has seemingly made a decision to err on the side of inclusiveness, as several states guilty of undermining democracy (Poland, the Philippines, India) have found themselves on the invitation list, notes J. Brian Atwood, a visiting scholar at Brown University’s Watson Institute. This approach is borne out by the experience of the National Democratic Institute (NDI) which, funded largely by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), has taken its cue from democrats on the ground, he writes for The Hill.

Credit: Carnegie

However, even if the Summit gets the basic framing right, considerable obstacles to substantive improvements to democracy still lie ahead, adds Søndergaard:

- The vague ideas that have so far been floated by the Biden administration need to become much more concrete to be transformed into an implementable agenda.

- A system for the transparent monitoring of progress will need to be established. Any efforts perceived as interfering in domestic issues are likely to be met by resistance.

- Finally, any meaningful efforts will have to be ongoing. As such, the real indicator of success for the Summit will be whether it becomes a one-off event or marks the beginning of continuing collaboration among democracies.

On the eve of the Summit, the National Endowment for Democracy will convene a forum featuring some of the most important voices from democratic struggles’ front-lines, including this year’s Nobel Peace Prize winner, Philippine journalist Maria Ressa.

Activists from Hong Kong, Nicaragua, Nigeria, and Russia will discuss global challenges to democracy in conversation with US Legislators. Some of the most dedicated democracy advocates will share insights and expertise on how to rebuild democratic momentum. Former heads of government who helped lead countries through democratic transitions will reflect on how to sustain democracy.

Activists from Hong Kong, Nicaragua, Nigeria, and Russia will discuss global challenges to democracy in conversation with US Legislators. Some of the most dedicated democracy advocates will share insights and expertise on how to rebuild democratic momentum. Former heads of government who helped lead countries through democratic transitions will reflect on how to sustain democracy.

Wed, December 8, 2021. 12:30 PM – 1:45 PM EST. Add to calendar. RSVP

Agenda

Maria Ressa on “The Global Threat to Democracy from Disinformation”

A conversation with Philippine journalist and 2021 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate.

“Rebuilding Democratic Momentum”

NED Chairman Kenneth Wollack in conversation with leading voices on democracy:

Madeleine Albright, Chair, National Democratic Institute

Senator Dan Sullivan, Chairman, International Republican Institute

Greg Lebedev, Chairman, Center for International Private Enterprise

“Meeting Authoritarian Challenges around the World”

“Meeting Authoritarian Challenges around the World”

Global Democracy Advocates in conversation with US legislators (TBC)

Berta Valle (Nicaragua)

Vladimir Kara-Murza (Russia)

Nathan Law (Hong Kong)

DJ Switch (Nigeria – right)

“Sustaining Democracy under Challenging Conditions”

Lessons learned from former heads of government

Ricardo Lagos, former President of Chile

José Ramos-Horta, former President of East Timor

Mikulas Dzurinda, former Prime Minister of Slovakia RSVP

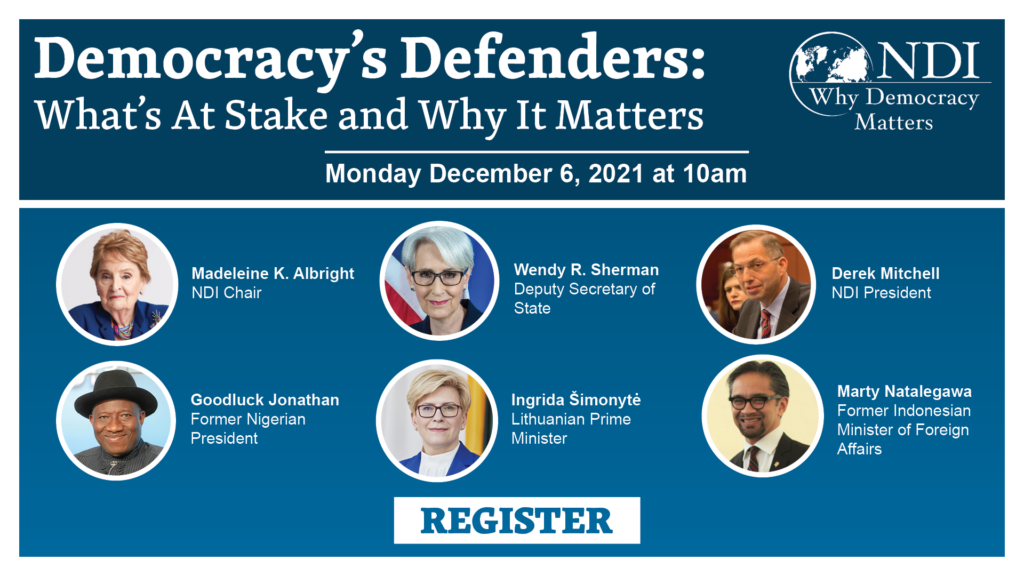

How can democracies form effective coalitions to defend democracy and ensure democracy delivers? Join leading Democracy Defenders as NDI kicks off a new Why Democracy Matters campaign! Opening Remarks by NDI Chair Madeleine K. Albright. Keynote Address on “Why Democracy Matters” by Deputy Secretary of State Wendy R. Sherman. Moderated by NDI President Derek Mitchell.

How can democracies form effective coalitions to defend democracy and ensure democracy delivers? Join leading Democracy Defenders as NDI kicks off a new Why Democracy Matters campaign! Opening Remarks by NDI Chair Madeleine K. Albright. Keynote Address on “Why Democracy Matters” by Deputy Secretary of State Wendy R. Sherman. Moderated by NDI President Derek Mitchell.

Panelists

Ingrida Šimonytė, Lithuanian Prime Minister

Goodluck Jonathan, Former Nigerian President

Marty Natalegawa, Former Indonesian Minister of Foreign Affairs

Monday, December 6th, 2021 10 am EST RSVP