Kyrgyzstan’s President Sooronbay Jeenbekov announced Tuesday that he plans to ask Parliament for a new vote on their prime minister nominee, Reuters reports [HT: Cipher Brief]:

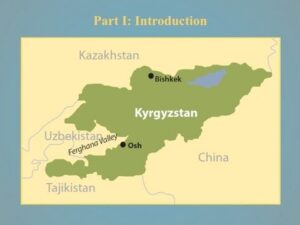

The move could be a formality but, if the vote fails, it could further deepen the political crisis in a strategically located country which also enjoys close ties with China and hosts a large Canadian-owned gold mining operation.

President Sooronbai Jeenbekov’s office gave no details of the talks with Dmitry Kozak, deputy head of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin administration, but said he had visited Kyrgyzstan on Monday. Sadyr Japarov, a nationalist politician who has been named prime minister by parliament but has not yet been confirmed in office by Jeenbekov, also attended the meeting, it said.

A popular uprising has overthrown a Kyrgyz government for the third time in less than two decades, confirming the country as a political outlier in Central Asia. But this month’s events put Kyrgyzstan in real danger of sinking into an abyss of confusion and chaos, notes Djoomart Otorbaev, Kyrgyzstan’s Prime Minister in 2014-15.

A popular uprising has overthrown a Kyrgyz government for the third time in less than two decades, confirming the country as a political outlier in Central Asia. But this month’s events put Kyrgyzstan in real danger of sinking into an abyss of confusion and chaos, notes Djoomart Otorbaev, Kyrgyzstan’s Prime Minister in 2014-15.

Many are asking how about 10,000 Kyrgyz citizens managed to accomplish in one night – toppling an unpopular regime – what hundreds of thousands of Belarusians have so far been unable to do in two months, he writes for Project Syndicate. Differences of mentality, customs, and experience seem to be key: unlike Belarusians, the Kyrgyz are far less constrained by the sense that legality outweighs justice. That inclination is of course a double-edged sword. The rebellious Kyrgyz have overthrown another government. But what comes next is far from clear.

After three revolutions in 15 years, sustainable democratization has been inhibited by several factors, including the influence of the northern and southern clans, said Central Asia expert Amirzhan Kosanov.

“Revolutions were carried out, but the most important thing wasn’t done — so that yesterday’s democrat who came to power on the wave of popular slogans didn’t turn into an authoritarian and a reason for the next popular unrest,” he said in an interview with Realnoe Vremya. “Unless this is done, unless there is a corresponding legal framework, the practice and tradition of zero-tolerance to the return to authoritarianism, revolutions will go on. And we will be doomed again and again to see another democratic déjà vu.”

“Revolutions were carried out, but the most important thing wasn’t done — so that yesterday’s democrat who came to power on the wave of popular slogans didn’t turn into an authoritarian and a reason for the next popular unrest,” he said in an interview with Realnoe Vremya. “Unless this is done, unless there is a corresponding legal framework, the practice and tradition of zero-tolerance to the return to authoritarianism, revolutions will go on. And we will be doomed again and again to see another democratic déjà vu.”

Robust social resilience

Beneath the county’s near constant political turmoil lies the robust social resilience of its citizens, notes Erica Marat, PhD, an Associate Professor at the College of International Security Affairs, National Defense University, and the author of The Politics of Police Reform: Society against the State in Post-Soviet Countries (Oxford University Press, 2018). People whose anger towards power-hungry politicians and a dysfunctional government drives them to rely on themselves and their communities rather than on state services. With every cycle of political turmoil and government dysfunction, civic networks only grow stronger, she writes for Open Democracy.

Kyrgyzstan’s president issued a decree imposing a one-week state of emergency in the capital Bishkek, under which protests would be banned, a curfew put in place, freedom of movement restricted, and the media “subject to controls” Human Rights Watch analyst Mihra Rittmann reports.

Parliament has yet to approve the decree, but Kyrgyzstan’s army is already patrolling the streets. According to the Media Policy Institute, the local media watchdog, media outlets and journalists have been harassed and threatened by hostile individuals and groups both during protests on Bishkek’s central square as well as at the editorial office of Sputnik Kyrgyzstan, a media outlet. Civil society has called on the authorities not to target political opposition, activists, and journalists, and to uphold the rule of law, she adds.

Organized crime, disorganized government

The events once again exposed the growing role of organized crime in Kyrgyz politics, adds Shairbek Juraev, a Marie Curie Fellow at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland. This is not news in Kyrgyzstan; many active politicians, including some party leaders, have semi-criminal (meaning criminal but legally not) background. In the past week, widespread reports pointed to criminal groups among the protesting crowds of different stripes. Acknowledging the issue, civil activists gathered a massive protest action named “The country without organized crime”. At the same time, the deputy speaker of the parliament Aida Kasymalieva reported she and other MPs were directly threatened by colleagues with criminal links.

The events once again exposed the growing role of organized crime in Kyrgyz politics, adds Shairbek Juraev, a Marie Curie Fellow at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland. This is not news in Kyrgyzstan; many active politicians, including some party leaders, have semi-criminal (meaning criminal but legally not) background. In the past week, widespread reports pointed to criminal groups among the protesting crowds of different stripes. Acknowledging the issue, civil activists gathered a massive protest action named “The country without organized crime”. At the same time, the deputy speaker of the parliament Aida Kasymalieva reported she and other MPs were directly threatened by colleagues with criminal links.

The standoff between the Sadyr Japarov and Omurbek Babanov camps reflects a greater divide in Kyrgyz society, adds Emma Svoboda:

- Japarov is a nationalist with strong support in the southern and rural regions of the country. His jail sentence stems from a protest he held in 2013 demanding nationalization of the Canadian-owned Kumtor gold mine.

- In contrast, Babanov and Toktogaziev are businessmen who are more outward looking; during Babanov’s unsuccessful 2017 campaign for president, the candidate pledged to bring more outside investment into the country and strengthen the business sector. Babanov and Toktogaziev also draw more support from young voters raised in the post-Soviet era of independence and growing globalization.

The two factions even differ in their use of language: Japarov’s rallies in Bishkek this week have been held largely in Kyrgyz, while Babanov and Toktogaziev speak to their supporters in Russian, she writes for Lawfare.

A joint investigation by OCCRP (above), Kloop, RFE/RL’s Radio Azattyk, and Bellingcat showed that former official Rayimbek Matraimov – nicknamed Raim Million – oversaw a large-scale transnational corruption scheme in collusion with the Abdukadyr family, Al Jazeera reports.

A joint investigation by OCCRP (above), Kloop, RFE/RL’s Radio Azattyk, and Bellingcat showed that former official Rayimbek Matraimov – nicknamed Raim Million – oversaw a large-scale transnational corruption scheme in collusion with the Abdukadyr family, Al Jazeera reports.

“Matraimov is a kingmaker who has always been in the shadows and he’s never had any blatant political ambitions. He is masterful in that sense. Yet, from behind the scenes, he has exerted massive influence on Kyrgyz politics,” Azim Azimov, a Kyrgyz political commentator told Al Jazeera.

“I always call them the Matraimov organisation because even though they are a clan, they operate like a corporation; they are buying their supporters,” he added. “For years now, they have been investing in the media and public speakers of various nature to promote the agenda that the Matraimov organisation see fit.”

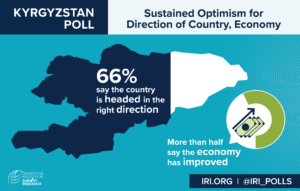

The current turmoil underscores popular frustration over the government’s mismanagement of COVID-19, high unemployment, rampant corruption and President Sooronbay Jeenbekov’s consolidation of power, said IRI Regional Director for Eurasia Stephen Nix (below).

Incisive analysis from @NEDemocracy partner @IRIglobal https://t.co/nYv7pk6mZE

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 12, 2020

Atlantic Council experts respond to the recent instability in Kyrgyzstan and what it means for the region and the international community:

Noah Tucker: US and EU should side with the next Kyrgyz generation

Baktybek Beshimov: Instability shows Kyrgyzstan is a failed state

Ariel Cohen: Kyrgyzstan is developing an immunity to authoritarianism.

Nurlan Namatov: Important challenges remain for Kyrgyzstan.

In 2013, the National Endowment for Democracy and the International Forum for Democratic Studies presented Nadira Eshmatova, Reagan-Fascell Democracy Fellow, NED with comments by Maria Lisitsyna, Project Manager with the Open Society Justice Initiative: A special presentation and discussion, moderated by Sally Blair of the Forum.