Sixty-three people died over the weekend in a crackdown by security forces against ongoing anti-government protests [HT: CFR], according to the semi-official Iraq High Commission for Human Rights. Iraq is not really “burning” – at least yet, says analyst Anthony H. Cordesman writes. But without major reforms, today’s protests can only be the prelude to more extremism, violence, and tragedy, he writes for the Center for Strategic and International Studies (HT:FDD).

in Ethiopia, at least sixty-seven people have died and another two hundred people have been injured in clashes during protests, CNN adds, in support of media mogul Jawar Mohammed, who has been critical of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s government.

Unemployment and sluggish economic growth are fueling social tension and popular protests in several Arab countries, the International Monetary Fund said Monday, Agence France-Presse reports (HT:FDD).

Unemployment and sluggish economic growth are fueling social tension and popular protests in several Arab countries, the International Monetary Fund said Monday, Agence France-Presse reports (HT:FDD).

A simple conclusion could be that the current wave of global unrest has no shared characteristics other than the tactic of taking to the streets. But I think there is more to it than that, says the Washington Post’s Jackson Diehl. Hong Kong and Egypt, Chile and Lebanon have two things in common: pervasive social media and a rising generation of discontented youth who are masters of it. The combination of the two has changed the balance of power between government and society in both democratic and authoritarian states, he writes:

This is a motivated generation, pushing for dramatic change in the political status quo. In that sense, the youth of 2019 are a little like those of 1968. Their command of new communications technologies makes it easy for them to attract followers, circumvent the usual channels of public debate and blindside governments [as a recent book – left – suggests]. They are able to mobilize large numbers on small issues, such as fare increases, and tap into general discontent that otherwise might have remained unexpressed.

This is a motivated generation, pushing for dramatic change in the political status quo. In that sense, the youth of 2019 are a little like those of 1968. Their command of new communications technologies makes it easy for them to attract followers, circumvent the usual channels of public debate and blindside governments [as a recent book – left – suggests]. They are able to mobilize large numbers on small issues, such as fare increases, and tap into general discontent that otherwise might have remained unexpressed.

“The mass protests they have generated have had very different aims in very different places. But they augur a new era of political conflict,” Diehl suggests.

But protests are also becoming much, much likelier to fail. Only 20 years ago, 70 percent of protests demanding systemic political change got it — a figure that had been growing steadily since the 1950s, the New York Times adds.

In the mid-2000s, that trend suddenly reversed. Worldwide, protesters’ success rate has since plummeted to only 30 percent, according to a study by Erica Chenoweth, a Harvard University political scientist who called the decline “staggering.” Four major trends explain the shift to the new normal of mass global protest and what it reveals about the world, according to The Interpreter’s Max Fisher and Amanda Taub:

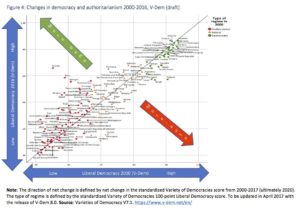

V-Dem

Democracy is stalling: For the first time since World War II, the number of countries moving toward authoritarianism is exceeding the number moving toward democracy, according to a recent V-Dem study by Anna Lürhmann and Staffan Lindberg of the University of Gothenburg….[N]ow that people aren’t getting democracy, it’s as if a release valve has been closed. That built-up pressure is getting released as explosions of mass outrage. …

Social media makes protests likelier to start, likelier to balloon in size and likelier to fail: A theory advanced by Zeynep Tufekci, [author of Twitter and Teargas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest], a scholar at the University of North Carolina, posits that social media makes it easier for activists to organize protests and to quickly draw once-unthinkable numbers — but that this is actually a liability…..

Social polarization has increased: People are more polarized along racial, class and partisan lines. As a result, they are likelier to cling to their sense of group identity and to see their group as under siege — compelling them to collectively rise up.

Authoritarian learning: In the mid-2000s, [autocrats] began to fight back with what Ms. Chenoweth called, in a 2017 paper, “joint efforts to develop, systematize, and report on techniques and best practices for containing such threats.”.. These cat-and-mouse strategies for frustrating and redirecting popular dissent without crushing it outright are a major reason that protests’ success rate has plummeted. …But such strategies also don’t really defeat dissent outright — so they may be helping to ensure future cycles of protests, maintaining the high global rate. RTWT

Authoritarian learning: In the mid-2000s, [autocrats] began to fight back with what Ms. Chenoweth called, in a 2017 paper, “joint efforts to develop, systematize, and report on techniques and best practices for containing such threats.”.. These cat-and-mouse strategies for frustrating and redirecting popular dissent without crushing it outright are a major reason that protests’ success rate has plummeted. …But such strategies also don’t really defeat dissent outright — so they may be helping to ensure future cycles of protests, maintaining the high global rate. RTWT

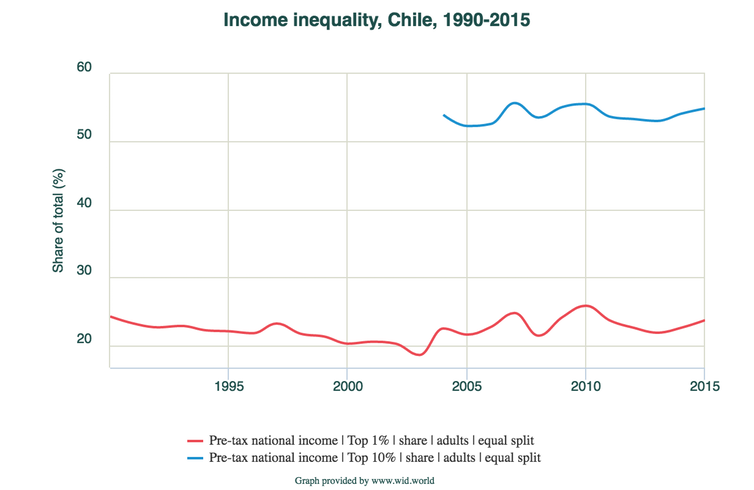

The economic and ideological legacies of the Pinochet era as well as the nature of Chile’s transition to democracy are key to understanding the reasons for the protests, argues Marieke Riethof, Senior Lecturer in Latin American Politics at the University of Liverpool. The anger of those on the streets is as much a reflection of the country’s high inequality (see diagram below) as it is of these unresolved legacies.

Journalist and #MeToo activist Sophia Huang Xueqin was arrested by Chinese police last week on charges of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” after publishing an online essay about the ongoing protests in Hong Kong, adds China Digital Times, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy. However, it remains unclear whether her online activities contributed to her arrest. The New York Times’ Javier C. Hernández reports.

As mass mobilization has become a pivotal aspect of global political struggle, After Protest: Pathways Beyond Mass Mobilization examines what happens when protests abate, addressing three specific elements across ten countries: how to categorize activists’ preferred pathways beyond protest, why activists choose these pathways, and how to understand the different outcomes, Carnegie’s Richard Youngs observes.

As mass mobilization has become a pivotal aspect of global political struggle, After Protest: Pathways Beyond Mass Mobilization examines what happens when protests abate, addressing three specific elements across ten countries: how to categorize activists’ preferred pathways beyond protest, why activists choose these pathways, and how to understand the different outcomes, Carnegie’s Richard Youngs observes.

Political analysts tend to see the more educated urban middle classes as the principal drivers of pro-democracy protests. But democratization is much more likely to follow when industrial workers are protesting, argue analysts , and These groups often combine a strong preference for democracy (especially in urbanized societies) with the capacity to push through democratizing changes, they wrote for the Post:

Industrial workers, in particular, can use unions, international labor networks and social democratic parties to coordinate powerful challenges against dictatorial regimes. Here, we agree with influential, in-depth studies of specific European and Latin American countries, which highlight the historical role of labor movements in pushing for universal suffrage and competitive multiparty elections.

While civil society and the media are often painted primarily as forces of opposition, a growing group of scholars and practitioners makes the case for their vital roles in building dialogue. The World Bank’s World Development Report 2017 provides empirical evidence for what some have long suspected: Coordination and cooperation, spanning social and political divides, is integral in ensuring good governance and achieving sustainable improvements in security, growth, and equity, the NED’s Center for International Media Assistance reports (above).