Paris is hosting a bilateral conference with representatives from about 50 countries to help Ukraine resist and rebuild after the war with Russia (above), specifically to identify the immediate needs of Ukrainians and how to meet them, and to help them recover from the conflict once it is over, AFP reports.

“It’s tangible proof Ukraine is not alone,” President Emmanuel Macron of France said at the opening of a one-day summit, flanked by Denys Shmyhal, Ukraine’s prime minister, and Olena Zelenska, Ukraine’s first lady.

“The fight you are waging is a fight for your freedom, your sovereignty,” Macron said. “But it is also a fight for the international order and for the stability of all of us,” the Times reports:

“The fight you are waging is a fight for your freedom, your sovereignty,” Macron said. “But it is also a fight for the international order and for the stability of all of us,” the Times reports:

The French leader also announced the creation of the “Paris mechanism” — a platform designed to ensure that donors coordinate urgent deliveries and match them to Ukrainian needs. Hubs in Poland and several other countries will collect international donations, including generators and heat pumps, that can be swiftly shuttled into Ukraine.

Humanitarian actors, which are used to operating in failed states, arrived in Ukraine with badly adjusted methods and were technologically outperformed by the Ukrainians, AFP reports:

“At the start of the conflict”, explained Francois Grunewald, Director General of France’s Group Urgence Rehabilitation Development (URD), an independent institute specialising in humanitarian practices, “they had to confront the very different dynamics of Ukrainian civil society, which is highly digitalised.” Ukrainian civil society groups quickly organised themselves on Facebook and Telegram. “We had two disconnected groups that took a lot of time to begin coordinating with each other,” he said.

“At the start of the conflict”, explained Francois Grunewald, Director General of France’s Group Urgence Rehabilitation Development (URD), an independent institute specialising in humanitarian practices, “they had to confront the very different dynamics of Ukrainian civil society, which is highly digitalised.” Ukrainian civil society groups quickly organised themselves on Facebook and Telegram. “We had two disconnected groups that took a lot of time to begin coordinating with each other,” he said.

For Caroline Brandao, a researcher in international humanitarian responses, international solidarity is not as strong as it was a few months ago. “We have, perhaps, arrived at a moment when we need to look at the paths we can take to show that the world has not lost interest in the conflict,” she suggested. “This conference can send a message of hope to Ukrainians, but it must not be full of empty promises.”

The hope that an armistice might be a route to the end of hostilities in Ukraine is based on three ideas, The FT’s Gideon Rachman writes:

The hope that an armistice might be a route to the end of hostilities in Ukraine is based on three ideas, The FT’s Gideon Rachman writes:

- First, neither Russia nor Ukraine is in a position to achieve total victory.

- Second, the political positions of the two countries are too far apart to make a peace agreement possible.

- Third, both countries are suffering severe losses that could make a ceasefire attractive.

Illiberal Poland and Hungary are taking a confrontational attitude toward the EU, but this doesn’t mean they are showing a supportive stance toward Russia. Things are not as simple as that, reports suggest.

Illiberal Poland and Hungary are taking a confrontational attitude toward the EU, but this doesn’t mean they are showing a supportive stance toward Russia. Things are not as simple as that, reports suggest.

Ivan Krastev (right), chairman of the Center for Liberal Strategies in Sofia, Bulgaria, has highlighted the increasing division between Hungary and Poland.

“Each of these crises divided the EU: the global financial crisis exhibited a classical North/South divide whereas the migration one caused an East/West fracture. Now paradoxically, with the Russian war, the divide occurred within the Eastern part of Europe,” he told the Paris-based Institut Montaigne.

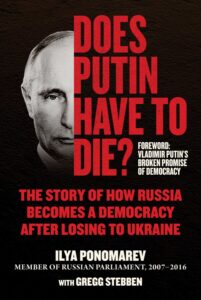

Vladimir Putin cancelled a press conference that has always been an unpleasant duty for him, The FT reports. “But it was a necessary ritual to maintain what he believed was a democratic regime”, said Tatiana Stanovaya, founder of R.Politik, a France-based political consultancy. The war has made the regime more “defiant” and freed it from the need to maintain the pretense of external decorum.

Vladimir Putin cancelled a press conference that has always been an unpleasant duty for him, The FT reports. “But it was a necessary ritual to maintain what he believed was a democratic regime”, said Tatiana Stanovaya, founder of R.Politik, a France-based political consultancy. The war has made the regime more “defiant” and freed it from the need to maintain the pretense of external decorum.

It would be reassuring to believe that the stream of disasters will bring reform if not revolution in Russia, adds Elliot Cohen, a professor at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. This is possible but unlikely.

It is not only that the mechanisms of repression are too strong: It is that, alas, Russian culture seems to be one of acquiescence even if coupled with mistrust of the Kremlin’s plans, he writes for The Wall Street Journal. Centuries of autocracy, followed by more than two generations of totalitarianism, have left their mark. Russia’s liberal heroes too often end up fleeing, exiled or simply murdered.

Ukrainian democracy had demonstrated considerable resilience under conditions of war, the Berlin-based Institut für Europäische Politik reports. “The biggest threat right now is: we are losing our best people. People who could push the state forward are dying in this war”, were the cautionary words of one speaker at a recent forum.

Other speakers (below) included Mariia Zolkina, security policy expert from the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation (DIF, Kyiv), Mykhailo Zhernakov, co-founder and chair of the Board of the DEJURE Foundation in Kyiv and Oksana Huss, researcher in the BIT-ACT research project at the University of Bologna and lecturer at the National University Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

“Each of these crises divided the EU: the global financial crisis exhibited a classical North/South divide whereas the migration one caused an East/West fracture,” @JoDemocracy contributor & @ThinkDemocracy associate #IvanKrastev told @i_montagne_.https://t.co/kcSEO3Awi6

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) December 13, 2022