Credit: Robert C. Jones/Small Wars Journal

China is ramping up its ‘sharp power’ efforts to discredit democracy, but brittle autocratic states are “Titanics,” supposedly unsinkable, yet essentially vulnerable, and are in any case unable to attract allies to contest the rules-based global order, analysts suggest.

China’s ruling Communist Party is exploiting the recrimination and rhetoric surrounding the U.S. election to promote Beijing’s favored argument that the United States is a fundamentally unstable place, notes David Wertime, POLITICO’s inaugural Editorial Director for China and the author of China Watcher. It’s a critique that supports the implicit bargain Beijing believes it’s reached with the Chinese people: less freedom than American life, in exchange for more unity, stability and safety.

The nail-biting race has evoked a sense of Chinese exceptionalism among some nationalistic netizens and further fueled their dismissive attitude toward democracy, he reports.

“Cast off your illusions and prepare for war.” POLITICO Screengrab/Weibo.com via Shen Lu

“China exploits U.S. chaos,” notes Mark Cohen of Berkeley Law School. “If the pandemic grows, [there are] possible security implications, including China moving against [the Taiwanese islands of] Quemoy or Matsu, or even Taiwan.”

Cornell University’s Yangyang Cheng believes “U.S.-China relations will deteriorate as a dysfunctional U.S. feeds China’s expanding ambitions, and ethno-nationalism grows in times of upheaval.”

But former NED Penn Kemble fellow Ali Wyne, a senior analyst for Global Macro at the Eurasia Group, believes “the concern of many allies and partners [is] that America’s domestic challenges are constraining its ability to pursue a consistent and constructive foreign policy. America’s external competitiveness depends in good measure on its internal competence,” he told Asia Times.

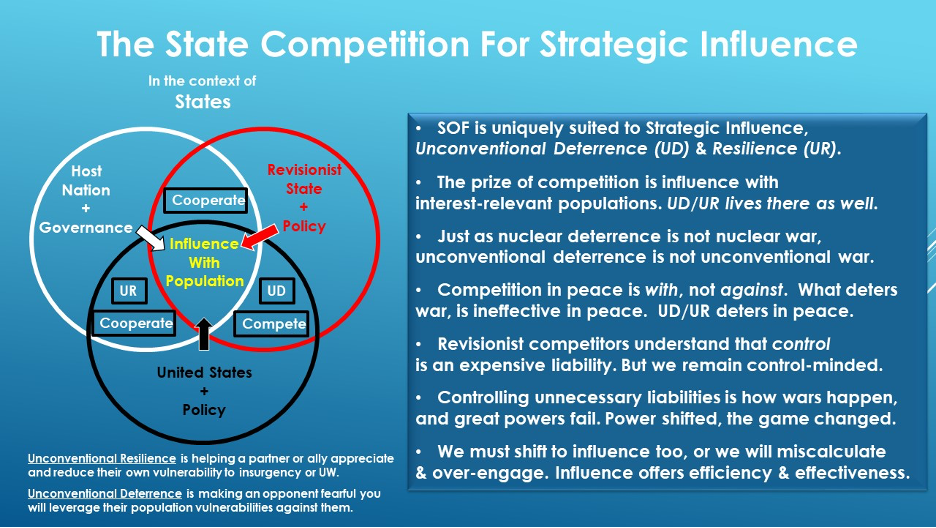

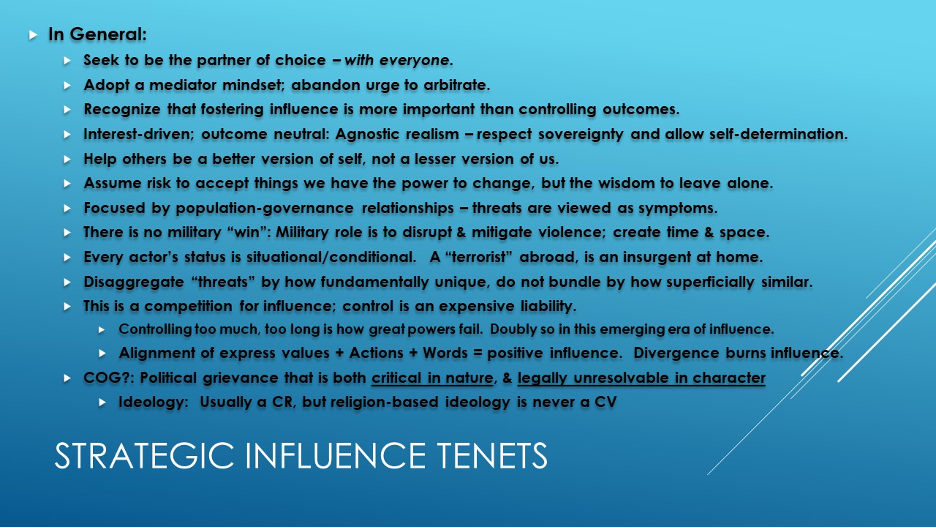

The ‘brittle states’ underpinning autocratic regimes are increasingly more fearful of their own populations. Many are “Titanics,” seemingly unsinkable, yet tragically vulnerable, says strategist Robert C. Jones.

The best defense for autocratic regimes is to conduct their own resilience operations to improve perceptions of their own governance, he writes for the Small Wars Journal. If they opt instead to crack down on populations they will only make our influence stronger, and their own situation worse. Unconventional deterrence encourages good governance.

Credit: Robert C. Jones/Small Wars Journal

Ideological framing of US-China competition on freedom versus authoritarian terms, is a narrative with built-in appeal elsewhere in the democratic world but less so in a region with few democratic or liberal governments, Asia Times reports.

China’s Communist Party aims to “use a contested election, together with America’s fumbled response to the coronavirus, to argue that its political system is superior to democracies,” said Ian Storey, a senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. But for member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), distrust in one major power may not mean greater trust in a rival power, say analysts.

“The contrast between the democratic and authoritarian models, as exemplified by the US and China respectively, is a false binary in Southeast Asia. Political ideology isn’t a preoccupation in the region in the same way as it is in other parts of the world. ASEAN’s membership alone is testament to this,” said Elina Noor, a visiting fellow at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia.

National Endowment for Democracy

The West’s “ideational hegemony” during the Cold War generated “astonishingly positive trends in areas the United States sought to influence—democracy, human rights, economic growth and development, economic freedom, and the rule of law,” notes Michael J. Mazarr, a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation.

China—like Russia—views the ideas associated with the reigning order as justifying regime change narratives which ultimately threaten the rule of the Communist Party. But the predominance of established democracies among the world’s leading economies and major powers, the power of national identity, and the need to build a global order in accord with the identities of the major powers, will be substantial barriers to China’s legitimate hegemony of any order, he writes for PRISM:

The emerging strategic competition reflects, at its core, a struggle over the context, the field in which world politics unfolds—the prevailing ideas, narratives, norms, rules, and institutions that shape states’ interests. This makes it an ideological competition, but of a specific sort. The revolutionary ideological adventurism central to Soviet and Chinese strategy in the Cold War is not characteristic of current Chinese policies. It is instead a competition between two would-be leaders of a governing ideational order, each offering a basic political model, essential economic principles, and other aspects of a set of norms and values.

The international paradigm as conceived here has four main pillars, Mazarr contends:

The international paradigm as conceived here has four main pillars, Mazarr contends:

- First are the prevailing global political and economic values—whether elites and populaces tend toward values such as democracy, liberal economic policies, free trade, and human rights. These could be measured by such yardsticks as total numbers of regimes reflecting certain values, indices of political and economic freedom, and public opinion polling on favored values.

- A second pillar of the international paradigm is cultural influences: Which countries, systems, peoples or groups set the global standards in cultural habits and in such areas as film, television, music, and literature? Influence in this pillar can be measured by prevalence of global cultural influence, opinion polls, and emergent habits and practices.

- The third pillar of the current paradigm is global rules and norms as established in international law, conventions, and practice. These range from the territorial non-aggression norm enshrined in the UN Charter and many other compacts, to the core elements of international maritime law and the law of war, and can be measured in terms of formal agreement as well as the degree to which they are respected.

- The fourth and final pillar is international institutions, both intergovernmental and nongovernmental. Influence here can be measured by leadership positions and the policy stances the institutions take.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

The primary U.S. task in the emerging competition is to preserve the astonishing advantages that accrue from being the hub of a shared and widely appreciated order of dominant ideas, norms, habits, and perspectives in each of these four pillars of the paradigm, Mazarr concludes. RTWT

The Chicago Council on Foreign Relations’ polling suggests that a majority of voters support the consensus on confronting China – a consensus that started in Washington’s foreign policy community, notes Christopher Sands, director of the Canada Institute at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The new American focus on competition with great power rivals China and Russia was signaled by the 2017 National Security Strategy of the United States, he writes for the Institute for Research on Public Policy’s Policy Options.

Ken McCallum, the incoming intelligence chief of the British domestic security service, MI5, said recently that if Russia’s influence operations are like bad weather, China’s growing operations are like climate change — far more destructive, NBC News adds.

“We are in a competition between democratic systems and autocratic systems of government,” said Laura Rosenberger, director of the Alliance for Securing Democracy, part of the nonprofit German Marshall Fund of the United States. “China has grown in its geopolitical and economic clout and is trying to portray itself as a system that is equally legitimate to democratic governance. That is fundamentally in opposition to U.S. interests.”

The Essence of the Strategic Competition with China. A must-read take from @RANDCorporation analyst Michael J Mazarr https://t.co/iLqROi7cz4

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) November 5, 2020